It's unfortunate that as the centuries pass, the people who struggle to apply science to human affliction fade out of public memory. Sometimes a name remains attached to a disorder, but usually the name means nothing to anyone except a specialist. As a species we have only one past (described by different histories), and it's a sad thing that too little of that past shapes our awareness of the present.

In England in 1866, a year after the end of the American Civil War and just a few years after the publication of Darwin's The Origin of Species, an obscure medical superintendent of an asylum for idiots in Surrey, England, published a short paper in a London hospital journal. The opening lines have become immortalized:

"Those who have given any attention to congenital mental lesions, must have been frequently puzzled how to arrange, in any satisfactory way, the different classes of this defect which may have come under their observation. Nor will the difficulty be lessened by an appeal to what has been written on the subject. The systems of classification are generally so vague and artificial, that, not only do they assist but feebly, in any mental arrangement of the phenomena which are presented, but they completely fail in exerting any practical influence on the subject."

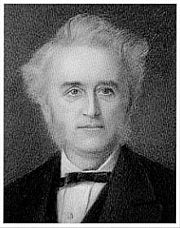

J. Langdon Down (1828-1896)

The author of the paper was J. Langdon Down. After discussing (in language now archaic) the physical appearance of various types of idiots, Down focused on what he called the "Mongolian" type:

"The Mongolian type of idiocy occurs in more than ten per cent. of the cases which are presented to me. They are always congenital idiots, and never result from accidents after uterine life... They are cases which very much repay judicious treatment... They have considerable power of imitation, even bordering on being mimics. They are humorous, and a lively sense of the ridiculous often colors their mimicry. This faculty of imitation may be cultivated to a very great extent, and a practical direction given to the results obtained. They are usually able to speak; the speech is thick and indistinct, but may be improved very greatly by a well-directed scheme of tongue gymnastics. The coordinating faculty is abnormal, but not so defective that it cannot be greatly strengthened. By systematic training, considerable manipulative power may be obtained..."

Thus was presented the first coherent description of what Down called "Mongolian idiocy"--mental retardation associated with certain apparent "Asiatic" facial features. Down's research was based on measurements of the diameters of the head and of the palate and on many series of clinical photographs. Mongolian idiocy (also called Mongolism) became a widely used term for nearly a hundred years, but in 1961 a group of genetic experts wrote to the British medical journal The Lancet suggesting four alternatives better suited than the name that implied a racial connection when the biological connection did not actually exist. The editor chose Down syndrome, and the new name was later endorsed by the World Health Organization.

What we now call Down syndrome, a consequence of a specific chromosome defect, has an apparent long history, including an evident described case in Saxon England in 800 AD, and a figurine with apparent Down syndrome features discovered in central Greece, the figurine dated to the Neolithic period about 7000 years ago.

Langdon Down had an interesting background. His father was a small-town grocer, and Langdon was taken out of school at the age of fourteen to spend the next four years behind the counter of his father's shop. When he was eighteen, Langdon had an experience that he later described as transformative. During a heavy summer rain, Langdon and his family took shelter in a cottage. Years later, he wrote about it: "I was brought into contact with a feeble minded girl, who waited on our party and for whom the question haunted me: could nothing for her be done? I had then not entered on a medical student's career but ever and anon ... the remembrance of that hapless girl presented itself to me and I longed to do something for her kind."

Down was far from a man with classical Victorian attitudes. He understood that for mentally retarded children social exclusion and the loneliness of limited social contact were major problems in all classes of society. Upper class children with a handicap passed their days isolated in the servants quarters of their homes--the children essentially a family secret. In the middle classes, such children were neglected in school and perceived as a poor educational investment. In the lower classes, retarded children were a tremendous burden for their struggling parents. Down proposed institutional training as the only solution to these problems.

The social conditions of the mentally retarded in America in the 19th century were hardly different from conditions in England. Thomas Jefferson's older sister was mentally retarded--his "idiot sister," as he called her--and he did his best to hide her existence, as well as the existence of a younger brother who was also apparently mentally retarded.

J. Langdon Down was also one of the few Victorians who accepted the advancement of women in medicine, in the law, and in the Church. He raised funds for the Suffragette movement. When he died in 1896, "shops closed and members of the public stood on the pavement in silent tribute as his cortege passed by."

Like anyone's life, the life of J. Langdon Down was a brief flash, an ephemeral sparkle long gone--but a sparkle that needs remembrance. It's our past. We own it and everything that ever happened in it.