I was 63 -- just about to turn 64 -- and prepared to retire from a busy gynecological practice. Everything was working as planned. Yet something seemed wrong. I felt jittery with a slight tremor in my right hand. At first I brushed it off, but when it continued I made an appointment with a neurologist friend. After a brief clinical exam he said: "Dan, you have Parkinson's disease." I still shudder when I speak those words.

I can still remember that sick feeling in my gut. I retreated into my cave and went into denial. He must be wrong, I thought, but time proved differently. Gradually the symptoms increased: more tremors, weakness in my legs, a slight imbalance, decreased mental acuity and slight depression. When once I held lives in my hands, I now had trouble holding a glass without fear of dropping it. I was aware of the progressive nature of this disease. I felt deprived of my dignity and my independence. My thoughts turned to anger. Why me?

Finding the right medicine to alleviate some of the symptoms was somewhat of a trial and error game. It felt like a jungle with little or no hope of escape.

Soon after, at the suggestion of a friend, I began to paint. While something I had never done before, it wasn't long before painting became part of my new daily routine. I just loved what was happening; I could take a brush, a canvas, some paints, and almost magically the pictures which filled my head began to transfer to the canvas. My attention span lengthened and people began to say nice things about my art.

With brush to canvas, my symptoms seemed to go away. My art became a meditation, and my studio a sanctuary, where the tremors stopped, my mind quieted, and I learned to see as I had never seen before. What I began to realize was the fact that my illness had something to teach me. The words "change, acceptance and patience" became my new mantra. I was now on a new path -- a path of hope.

From something bad comes something good. This is what the Torah tells us and what I was reminded recently when I spoke with neurologist and Tel Aviv University professor Dr. Rivka Inzelberg. My experience with Parkinson's and art mimics her current research (recently published in Behavioral Neuroscience): that despite the loss of prominent motor skills, artistic capacities are enhanced -- or are even emerged -- in Parkinson's patients undergoing treatment. A paradox I've experienced, but never verbalized.

Prof. Inzelberg first noticed this phenomenon in her Sheba Medical Center clinic, when her patients started bringing her their artwork. After examining the medical literature regarding this rise in creativity, she discovered the patients were all being treated with some form of dopamine.

She predicts the increase in happiness or satisfaction that dopamine provides could be triggering this creative drive. Or perhaps, she explains, we are expressing latent talents that we never had the courage to show before -- since dopamine is also connected to a loss of impulse control. The creative spike could stem from this lowering of inhibitions.

So in some way, as she put it, Parkinson's has been like a gift bestowed upon me and others like me to enhance our gifts, which would likely be unseen had we not gotten this disease. What a light bulb that was. Since speaking with Dr. Inzelberg, I have a new outlook -- a new way of seeing my illness.

It's a beautiful thing. Although I experience tremors, I'm able to paint almost every day, often for hours at a time, in the little studio I've set up in my house. I just can't get enough. My mind clears and I am in a different world... Not only is it an escape, but a new adventure -- a release of what was a part of me, in hiding for almost 70 years. I paint everything I'm drawn to and have noticed my eyes look at things differently. Before I merely looked at things; now I see them, really see the minor shapes, lines and touches of color -- for example, in a flower. Perhaps Van Gogh, too, suffered from excess dopamine?

In her research, Professor Inzelberg points out that dopamine and art have long been connected, actually citing the example of Van Gogh, who suffered from psychosis. It's possible that his creativity was the result of this psychosis and a spontaneous spiking of dopamine levels in the brain.

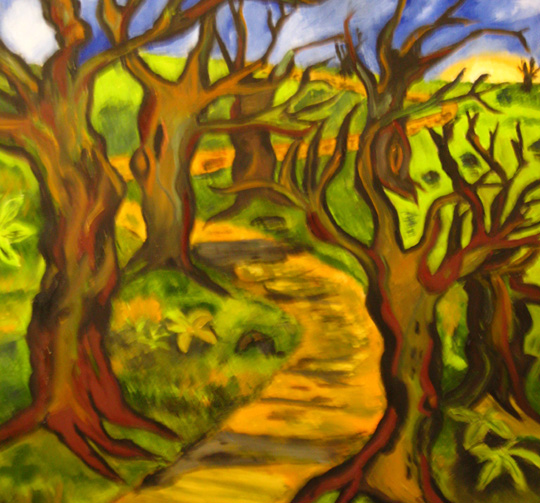

In some of my early thoughts on what was happening to me, I pictured myself wandering through a jungle of gnarly trees on a path that seemed to traverse the jungle. The trees unconsciously reminded me of the woods that Dorothy passed through in The Wizard of Oz. My thoughts were brought to life in a painting that titled my first solo exhibition: Painting a path through the Parkinson's Jungle. If you look closely at the piece, the path winds through the "dendrite"-like branches and eventually appears to exit the forest. But to where?

There appears to be a light at the end of the path, much like the light that Dr. Inzelberg foresees in some of us with this disease. With her work, we have a glimmer of hope that research will go further to eventually find a cure. In the meantime... I'll be painting.