In 1978, Al Jaffee got me into trouble with my fifth grade teacher, and I've been grateful ever since.

I thought his series on dealing with dog droppings in Mad Magazine and in his book Al Jaffee's Mad Inventions was so funny that I made the mistake of including "doggie doo" in many of my papers. My instructor didn't share my delight.

I'm not the only youngster who's found Jaffee's work to be the guiltiest of pleasures. Since 1941, he's been drawing or writing cartoons that have delighted children and adults who are brave enough to admit that his irreverence and skillful drawing are compulsively readable.

When thinkers like Beavis and Butt-Head and Eric Cartman have decreed that reading "sucks ass," Jaffe's text and illustrations have made literacy as delightful for me and millions of other youngsters as any other vice.  If it weren't for Al Jaffee and the rest of the "Usual Gang of Idiots" at Mad, it's doubtful I would have read James Joyce or Jonathan Franzen when I became older.

If it weren't for Al Jaffee and the rest of the "Usual Gang of Idiots" at Mad, it's doubtful I would have read James Joyce or Jonathan Franzen when I became older.

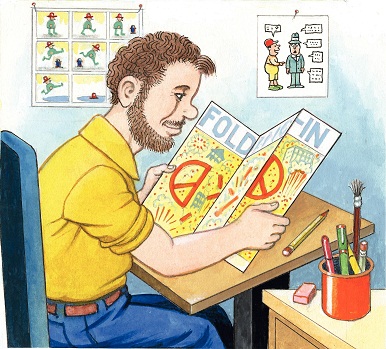

At 89, Jaffee has been contributing for Mad since 1954 and has been the senior member of the Gang. In almost every issue of Mad since 1964, he's created the Fold-In, which appears inside the back cover. It's a visual riddle in which the picture changes as the reader folds it in. For example, a recent Fold-In asked readers to identify an institution that was "too big to fail." The answer was not an investment bank but Kim Kardashian's butt.

He's also provided a long series called Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions, where he suggests snide responses that are guaranteed to entertain the people uttering them, if they survive the fury of the questioners.

Jaffee's unique legacy didn't emerge from nowhere. In Mary-Lou Weisman's new biography, Al Jaffee's Mad Life, he recounts his turbulent upbringing in Savannah, Ga., Zarasai, Lithuania and finally the Big Apple, where I contacted him by phone.

Jaffee's mother, Mildred Gordon Jaffee, took him and his brothers away from their home, against his father's wishes, to live in the Jewish section of Zarasai. She felt out of place in the secular, Gentile world of Savannah. In frank and vivid detail, Mad Life recounts how Jaffee and his brothers dealt with the backward conditions of the town and the anti-Semitism they encountered.

Twice, his mother brought them to Lithuania, and twice his father, Morris Jaffee, sacrificed everything to bring them back. Jaffee's mother stayed put, but in the wake of World War II, she was most likely murdered by Nazis or Lithuanian partisans who were eager to collaborate with them.

Despite a long series of misfortunes, Jaffee comes across as a contented man who has made people of all ages happy by poking fun at the absurdities of the adult world.

My fondness for your work got me in trouble when I was in the fifth grade.

So you did Snappy Answers, right?

Actually, it was Al Jaffee's Mad Inventions, believe it or not.

Oh, really?

I just thought your doggie doo solutions were really funny.

That's one of my favorites, too. Frequently when I'm interviewed, people ask me, "do you ever do things that are in bad taste and get reprimanded for it?" and I said the only one I can think of really is the solutions to the big city doggie doo problem.

I even masked that by telling them that what they're looking at is actually something else. Anyway, I got away with it. Actually, I opened up with a disclaimer. I said when you see advertisements on TV for false teeth; they never show the false teeth. They showed two plastic disks. So I said in this case, whenever you see what you think might be "offending matter," actually, they're sausages.

Another thing I remember about the book is that it featured make believe inventions that years later I swear I saw in the real world.

Yes. That has happened a number of times. For me, to invent things is easy. I focus on things that annoy me, and then I say something like why don't they do this? I don't have to actually go to the trouble of building it and getting it patented and going through all that kind of stuff. I just make a drawing of my idea, and it looks like it will work, and then somebody comes along.

It happened with a smokeless ashtray that I came up with in a smoking article (published in 1976). Someone actually built it and even mentioned--I don't know  if they mentioned my name or Mad's name, but they were inspired by it in the patent.

if they mentioned my name or Mad's name, but they were inspired by it in the patent.

From reading the new biography,...

You mean Al Jaffee's Mad Life? Did I say that loud enough and clear enough?

Yes. It's really astonishing how well you've remembered your childhood.

I guess people do remember traumatic childhoods. It makes a big impression on you, and if you were in a state of high anxiety all the time, that's what I guess my early life was pretty much like.

You describe your mother locking you and your brothers in the house while she went out to pray in the afternoon.

Yes, she did that. We had to figure out all sorts of inventive ways to solve bathroom problems because there was no interior bathroom, only outhouses in those days. And then of course we had to scrounge for food. She would forget that she was leaving us for long, long periods of time. But somehow we managed to survive.

Do you think that growing up in shtetl like you did as a child gave you advantages when you became an adult?

I think to some degree the answer would be yes because if you cast a child on a desert island and picked him up a couple of years later, he'd be pretty well equipped to take care of himself for the rest of his life. We had to fend for ourselves in every area. We learned new languages. We had to learn the customs of the town and how to avoid getting killed by people who don't like you. I think it helped a lot of my adult life because I learned to take care of myself.

Ms. Weisman has known you for three decades. Do you think anyone else could have gotten you to open up as easily about your childhood?

You respond differently to different people. With Mary Lou and I, our families, hit it off very well from the beginning, so it was very easy for me to talk to Mary Lou, and she's a very intelligent woman who asks interesting questions. She stirred up memories that I didn't think I had anymore. In this particular case, Mary Lou was a wonderful interviewer, and I was able to remember a lot of things I thought I had totally forgotten.

But if somebody else who might have rubbed me the wrong way, I might not have felt like opening up.

In the book, you describe the death of your siblings and what amounts to the murder of your mother.

Yes, that's true. Going back to the previous question, when you grow up in difficult circumstances, you learn how to make the best of things and how to survive. One of the survival mechanisms that I learned was not to dwell on sentimentality or tragedy or any of the emotional things, and just move on.

Looking back on my life was like looking back at an old movie. I just didn't have a great investment in emotion in it, as if it had happened to someone else.

Would that have had some influence on the cartoons you illustrated the book with?

That's a very good question because so many people are telling me the drawing style and the book is not at all like what I've been doing for many, many, many years in Mad Magazine and my newspaper comic strip and various other things, so for some reason, I didn't plan it, but when I sat down to draw it, it was as if I was feeling the scenes I had lived through, I think the drawings came out like something more like something for Grimm's Fairy Tales than for Mad Magazine.

One of the things that's great about the book is that we get to see several of the styles you've used.

I did not sit down and say what kind of a style for a little town in Lithuania. I didn't go through any of that. I just started. It's as if my hand was moving automatically. It's hard to explain why you're in a creative mood.

Jaffee and his mother deal with the problems of carrying jam by train from Al Jaffee's Mad Life. © 2010 Al Jaffee, used by permission.

Antonio Prohías (Spy vs. Spy) was a refugee from Castro's Cuba, and Sergio Aragonés' (the margin art in Mad) parents fled to Mexico from Franco's Spain. Considering your own situation, was it common at Mad to have political refugees or the children of refugees?

I don't think it was, but there's another thing that ties the three of us together, which is that we do a lot work in pantomime. In the case of Antonio Prohías, he had difficulty learning English. He never did really learn it. So it was very natural for him to come up with a wordless feature like Spy vs. Spy.

Sergio, also coming from Mexico, couldn't speak English well, but he could trial like a wiz. Mad was immediately fascinated by his work. I'd describe him as someone who speaks in pictures. And he literally does tell complete stories without a word in it. And of course when I did my newspaper feature, Tall Tales, it was primarily without words, especially at the beginning. So we have that pantomime in common.

It really is the purest form of cartoon communication when you can get across complicated ideas with only the drawing doing the talking, not the caption underneath. There are cartoons that are just stick figures, and they have a funny caption, and it gets the gag across. But pantomime it is much more difficult. I'm proud to be grouped with Antonio and Sergio.

You're not a slacker when it comes to words, though. I remember reading an article you did on built-in obsolescence where you were describing watchbands and hidden rot spots. You subtly added, "Metal takes longer."

The freedom that we had at Mad allowed me to do anything that I wanted. I did get off some pretty good captions.

I did love the delicate caption for the "Jackal Retching."

The "Jackal Retching," that was an article written by Larry Siegel. I will not take credit for any of the writing in that. I can only take credit for the depiction of the jackal. Larry wrote everything in that article.

The most memorable part of that image for me though, was the mouse in the corner of the illustration using a leaf to shield itself from the spew.

That's a bit of picture writing. Larry Siegel, when he wrote the script, it was all done on a typewriter. He didn't do any of little sketches or anything like that, which I normally do in my scripts.

In my scripts, if I was writing a script like that for another artist, the little mouse would have been in my rough drawing. But in this case, any of the secondary material that's in the picture, whether it's the attitude of the jackal leaning against a tree holding his stomach, or the little mouse running around, all those things are my additions. And I'm very proud of the way that came out.

You, Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder all went to the same New York high school (The High School of Music & Art). What was it about that school that produced all three of you?

There were many more in addition to us. Al Feldstein went to the new School of Art as well, and he was the editor of Mad much a longer than Harvey ever was. Cartooning, humorous stuff and satire was not encouraged in the High School of Music & Art. Music and art was basically fine art and fine music, when I say fine music, I mean classical music. The school was founded on the basis of the classics. We had oil painting from models, everything in the art field. But cartooning was verboten.

Will Elder once came in. He had seen Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and he loved them, and he drew them to show us in class. The teacher yanked it out of his hands and said, "Don't ever bring garbage like that into the school again." I don't think everybody felt that way. In fact, one of my teachers collected my cartoons in an album, but the curriculum in the school was focused on the classics in art and the classics in music.

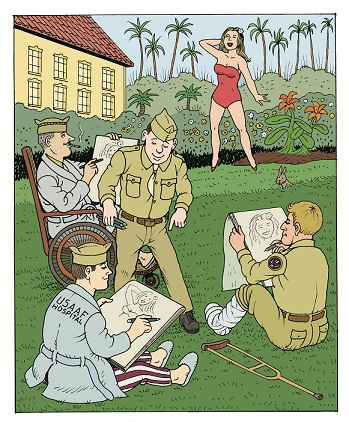

Jaffee (center) instructs wounded World War II vets in drawing from Al Jaffee's Mad Life. © 2010 Al Jaffee, used by permission.

You worked with Stan Lee before either of you became famous.

I worked with Stan Lee when I was 21 and Stan Lee was 19. That's when we came together.

The work you two did together was nothing like the superhero comics he did later or the tone of the pieces that you did with Mad, Humbug or Trump.

You're absolutely right. When I went to work for Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon had been the kingpins of Timely Comics (the predecessor of Marvel), as it was known at that time. Stan Lee took over.

Humor was the only thing they were doing. They had a Captain America because the war had been on for a while, and I think they might have had the Human Torch and a number of other things.

Stan was primarily involved in the humor part of it. In fact, he even created a feature called The Imp, that I at one time penciled. We had a lot of animal strips. I created Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal. But later on, when the comic book business was going downhill, Stan Lee, I think, saved it by getting heavily involved in the superhero business.

I never did superheroes from him. I did teenage stuff. I did animals. I did that kind of stuff.

It's still possible to pick up a copy of Mad and see one of your Fold-Ins. Why have you kept at it after all these years?

I still do. As a matter of fact, I'm on Fold-In #417 now. May I mention the fact that there's going to be a box set of four books of Fold-Ins coming out this spring?

I guess all 400 Fold-Ins will be in it. It should be very nice. I'm a little bit amazed that it's gone on so long myself. As a matter of fact, I'm working on one right now.

The last one you did was on institutions that are too "big to fail."

Oh, yes. It turns out to be Kim (Kardashian's butt).

Is it true that you produced it by first drawing her and then the stuff that fools the reader in the middle?

I'm going to reveal the secret of it, and then everybody in the country will now be able to do Fold-Ins ad nauseum. You work backwards. You do the answer first, and then you spread it apart and do the middle part. See how simple that is?

But it takes you two weeks to do these, and don't you have to fight hand tremors?

I do. That's why it takes so long. I have something that's called "essential tremor." It's a misnomer. Why it's essential--it's certainly not essential as far as I'm concerned. I have it.

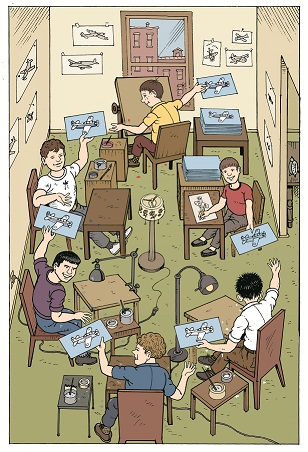

Jaffee and his brothers developed an assembly line approach to art in Al Jaffee's Mad Life. © 2010 Al Jaffee, used by permission.

I have to hold my drawing hand with my left hand to steady it. It's all part of reinventing yourself to suit the occasion. I started doing that when I was a little kid out of necessity, and now I'm doing it as an adult as a necessity. Never give up: That's the slogan. Just keep on truckin'.

You've also been advertising with Fold-Ins because in the last issue of Mad, you had a Fold-In that promoted the new televised version of the magazine.

Yes, on the Cartoon Network. They commissioned me to do that. I've done a number of commercial Fold-In's, maybe a dozen or so.

I did four of then for the Chrysler Caliber automobile. You know where Chrysler is right now? It was a nice assignment, and their ad were printed on the back page of Mad, so I wound with a Mad Fold-In on the inside and the outside. So, it mangled the magazine.

I have a feeling we'll know who's been reading the box set for free.

That's what happens with putting it in a bookstore. You'll come back and find a jumble of bent pages.

There's a lot of museum quality work that's reproduced in the current book. Do you wish that people had seen that was well as your cartoons?

To be honest, I sometimes wonder where my fine art ability would have taken me. When I was at the High School of Music & Art, I didn't do any cartooning except during lunch hour or when sitting around in study room when I would do funny little cartoons of whatever subject we were working on.

My work was always on exhibit. I would have to admit I was in the top echelons of the fine artwork. So, I often wonder if I had accepted the scholarship and steered a career in fine art whether I would be known as a gallery painter. But you never get a second chance to redo a career. You've got to be satisfied with whatever you've got.

You could say though that you've influenced generations of children who wanted to get in trouble with their parents. How does it feel to make people want to offer snappy answers to stupid questions?

That's one of my finer points. I would be lying if I said it doesn't mean anything to me. It means a lot me because through the years I have run into so many people who have told me how much they've enjoyed these kinds of things that I did. And I know they were being honest, and it's very gratifying to know that I could have connected with a five or six or eight-year-old kid on some level where they got a lot of enjoyment out of it. That makes me feel very good.

All Artwork © 2010 Al Jaffee, used by permission.