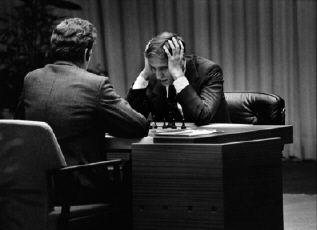

By the time he died in 2008, Bobby Fischer had proven that chess was more than a simple board game. His takedown of world champion Boris Spassky from the Soviet Union in 1972 grabbed more headlines and more airtime than a little break-in at the Watergate Hotel. The Soviets dominated the chess world, so Fischer's victory resonated throughout the western world. When Fischer wavered about flying to Iceland to compete, Henry Kissinger personally called him to persuade him to face Spassky.

Fischer popularized the game

After that, he became a fugitive for violating U.S. sanctions against the Belgrade government. Fischer's increasingly bizarre, truculent behavior alienated friends and family and landed him in serious legal trouble. He also started giving radio interviews where he spouted vitriolic anti-Semitic and anti-American tirades despite the fact that is own ancestry was Jewish.

Liz Garbus' new documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World skillfully puts both

Fischer's achievements and his descent into insanity into perspective. It airs at 9:00 p.m. EST on HBO on Monday, June 6. The film, which I caught earlier this year at the True/False Film Festival in Columbia, MO, brings the tension of the Cold War to life and explains why Fischer's chess matches captured public attention. By demolishing Soviet superiority in the game, Fischer proved that all people really had to fear in the '70s was gaudy polyester.

Garbus's previous films have demonstrated that she can handle complicated subjects like Bobby Fischer and do them justice. She and Jonathan Stack shared an Oscar nomination for The Farm: Angola, USA. She's also explored how the mind is altered by drugs in the "Brain Imaging" section of the HBO series Addiction and demonstrated how fighting for First Amendment rights can be as unpopular as it is necessary with Shouting Fire: Stories from the Edge of Free Speech. That film featured her father, First Amendment attorney Martin Garbus.

Contacted by phone in New York, Garbus explained how Fischer's most deadly opponent wound up being himself.

In a lot of your films you've worked with your subjects, like the prisoners in The Farm or your dad in Shouting Fire, so what was it like to cover somebody who couldn't speak for himself?

When you make a film about somebody who's no longer there and they're not there to speak for themselves, you feel an enormous responsibility towards Fischer to try to get it right, to tell the story in a way that's complete and full, from many angles and with compassion.

This is sort of a David and Goliath story because Boris Spassky had come into this from a pretty pampered background, and you provide many examples in the film of how Fischer came from anything but that.

That's right. The Soviet chess operation was known as the "Soviet Chess Machine" because the Russians were totally focused on producing grandmasters and ultimately champions. The kids were nurtured by the State early on if they had promise and were sort of taken under their wing and tutored, and they had teams and were given enormous support.

And Bobby had some very important teachers, but he certainly didn't have that kind of government support or backing. Therefore, it was unbalanced in that sense.

Because film is a visual medium, how do you make something as static as a chess match look interesting on screen?

For viewers outside the chess world, there has to be just the right amount of chess in the movie for it to be true to Bobby Fischer and to understand the key kind of turning points in the movie. But there also has to not be too much chess so as not to turn off the non-chess audience. Quite honestly, Bobby Fischer's life story and the way that he behaved off the table are as much the subject of this film or more the subject of this film than the play on the table. So, I think that's where the heart of the story was.

You eschewed chronological order with the movie. How did you decide on how to structure the movie?

I always wanted the match of '72, which was such a wonderfully thrilling period to be the narrative spine of the film. I wanted the film to be about a sports match, which it was, and a sports match with political, social, cultural implications. And so we sort of structured it around the match and wove in Bobby's biography and elements about the time period through the narrative spine of the match.

The experts you located to talk about it were people like Garry Kasparov and Susan Polgar who can explain chess to outsiders to the game. Was it tough to find people who had the background in chess but could still talk to a regular person?

Garry Kasparov was not just interesting to talk to about the chess itself. Garry was used to talk about what chess meant in Russia and the Soviet Union at the time.

We really brought Susan in specifically to kind of talk about the games and kind of give a sense of the narrative and dramatic turning points in the match from the chess point of view. We studied it, and we worked with her on what were the moments on what we wanted to dramatize and how they would kind of make sense to people who didn't have a real sense of chess, which you have to assume most of your audience doesn't have that. Susan is, of course, very charismatic, clear and telegenic, so she was wonderful for that. I also think it turned out that some people we didn't expect to be bringing that to the table in the same way did.

I think that it turned out that Dr. Anthony Saidy was wonderfully dramatic in the way he would talk about the chess matches and make parallels to other types of arts like music or painting, so that people could feel inside the matches. As well as (the late) Larry Evans, he did that as well. They're just great speakers, and they're all broadly intelligent and can relate chess to other mediums that maybe people understand better.

When you included the interview with painter Leroy Neiman (Garbus starts laughing), my audience in Columbia, Mo. fell out of their chairs when they saw him with his 70s hair and thick mustache.

I can't take credit for that except for my selection of really great, great '70s footage.

This is a period when you would have been about two. How much did you learn about a period that you probably wouldn't remember?

I've studied the Cold War, so I knew about it. I've studied film and history when I was in college (at Brown University). I've always been pretty well read on The Cold War. But I certainly did not appreciate how important chess was in America in 1971 and 1972, the years leading up to the match: how it would bump Watergate as the top story on the (NBC) Nightly News. I certainly did not appreciate that, and it was a wonderful journey into that world.

Fischer is still a controversial figure, but you did get cooperation from Dr. Saidy

and Fischer's brother in law (Russell Targ), both of whom were very close to him. How hard did you have to work to get their trust?

Hmm. Dr. Saidy was sort of an angel for us. He was not just an interview subject. He was somebody who sort of gave us advice and sort of guided us through the entire process. He would sort of connect us with other people in the chess world or suggest how to reach them or what parts might be of interest to them. He was sort of a guiding angel the whole way through.

I can't say why Saidy decided to trust us so much. I think he had seen some of my other work, and he's such a kind of cultured, well-expansive person that he appreciated documentary pursuits. Therefore, he really helped us and worked with us. As for Russell Targ, why did he choose to open up to us? I don't know. Russell was pretty forthcoming and ready to be interviewed.

There were some people who would not sit for an interview. Bill Lombardy, who was Bobby's second when he went to Reykjavik, and was a close friend of Bobby's all through his childhood, chose not to be interviewed. It's hard to understand everybody's motives in these things.

Was it tough to hear the hate-filled things that Fischer would say on the radio broadcasts? I felt sick to my stomach just hearing the stuff he said about 9/11.

Bobby said some pretty awful things. We kind of culled his radio call-ins

Do we have any idea what kind of mental condition he might have been suffering from?

He never sought psychiatric intervention or never would see a doctor and allow himself to be analyzed, so any kind of diagnosis on his mental health would be speculation.

In the footage of him that you've located and used in the film, you can see the madness to come. When he's asked what he reads, he names the tabloid Confidential.

Exactly. I think that Bobby was interested in some conspiracy-oriented stuff early on. Most people who knew Bobby when he was young said he was a nice kid. He definitely did not display

that kind of behavior until much later on. It's very sad.

One of the things that must have traumatized him was the fact that he had been a member of the Church of God and then was disillusioned with it.

He was very involved with the Church of God, and they provided an apartment for him and made a lot of money off of Bobby and provided sort of a community for Bobby. When their prophesies patently did not come true, Bobby was very much at sea.

His upbringing was pretty fascinating, too. His mother Regina could be described as absentee.

Bobby grew up very poor. His mother was a single mother who was working two jobs in order to support the family. Yes, she was not around a lot. Bobby's childhood was relatively unsupervised. Chess sort of filled the time in his life.

Your film is coming out almost a week after Bosnian Serb General Ratko Mladic has been arrested for taking part in the genocide that occurred while Fischer was playing in the chess showdown with Boris Spassky in Belgrade, Yugoslavia in 1992. What's it like to have those headlines coming out again after all these years?

Bobby played chess in Yugoslavia, while there was genocide going on there. He violated U.S. sanctions by playing there. However, there were people who were selling arms to the Yugoslavian government, and they weren't indicted for that behavior. Bobby's involvement in Yugoslavian politics at the time was really quite minimal.

All photos by Harry Benson ©2011 Moxie Firecracker Films, used by permission.