Eykyn Maclean Gallery is showing the 11 Twomblys in late collector/dealer Ileana Sonnabend's personal collection until May 19th, so I hied myself uptown the other day to take a look.

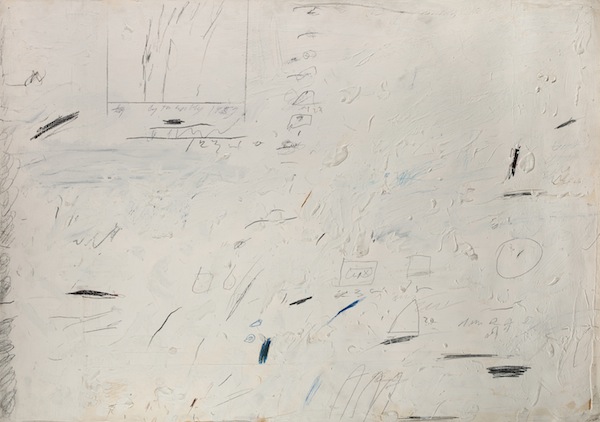

Cy Twombly, Sperlonga Drawing, 1959, tempera, pencil, and pastel on paper, 27 x 391⁄2 in., Sonnabend Collection, New York, ©Cy Twombly Foundation

Even decades after the fact, Twombly remains a difficult artist to approach. Let's sneak up on the idea of Twombly. In 1999, wunderkind Harmony Korine made a movie called julien donkey-boy. It was the first American film awarded a Dogme certificate by the faux-austere Dogme 95 filmmaker gang in Denmark. julien donkey-boy was not faux austere, it was the real thing. Actually, it was nearly unwatchable, a salad of enlarged, low-rez digital video heaped atop a simple and ugly story. For all that, it was significant, because it pushed the film medium so far that the seams started to show. When film is comfortable, and functioning properly, it seems flawless; the medium itself slips into invisibility. So you tend not to ask, "How does this work? Why does this work?" Those are important questions, and julien donkey-boy, in disrupting our ability to just watch the movie, thrusts them into the foreground.

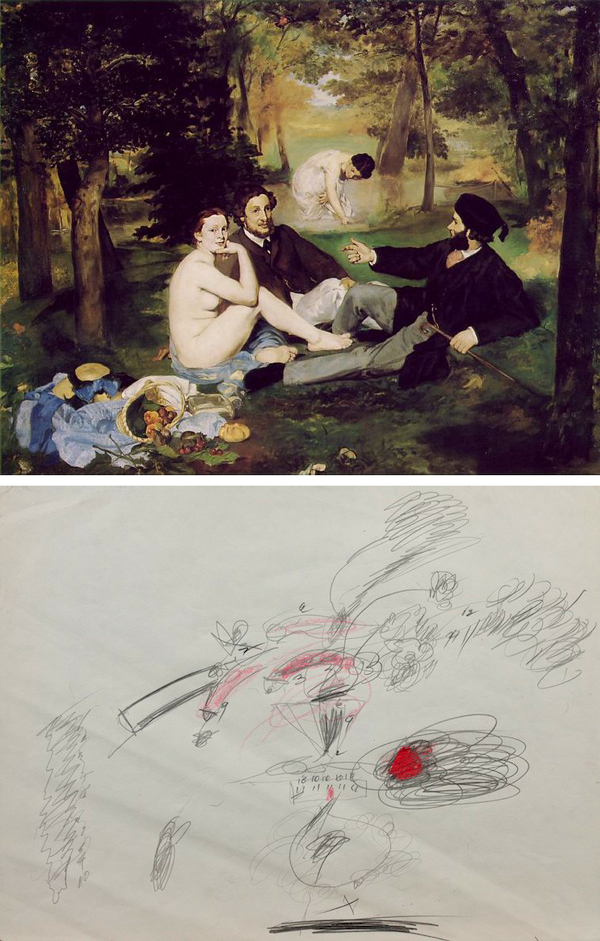

This is Twombly's starting point as an artist. He shows up at the Déjeuner sur l'Herbe with a backhoe, chases off the dandies and nudists, cuts down the forest, and excavates to bedrock.

before and after:

Édouard Manet, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1863, oil on canvas, 81.9x103.9 in., Musée d'Orsay, via Wikipedia

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1960-61, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 10 ½ x 13 ¾ in., Sonnabend Collection, New York, © Cy Twombly Foundation

This is not pleasant, or even particularly civilized. But it's important to sometimes ask how we know what we know. Twombly does not exist outside of visual art, like pure Dada, which is essentially conceptual. He subscribes to the visual tradition. This gives him the affinity and perspective to pull a Korine with it, to scrape off the flesh until the bones of grammar emerge.

The work in Sonnabend's collection seems to me to divide into two categories, one reductive and the other constructive.

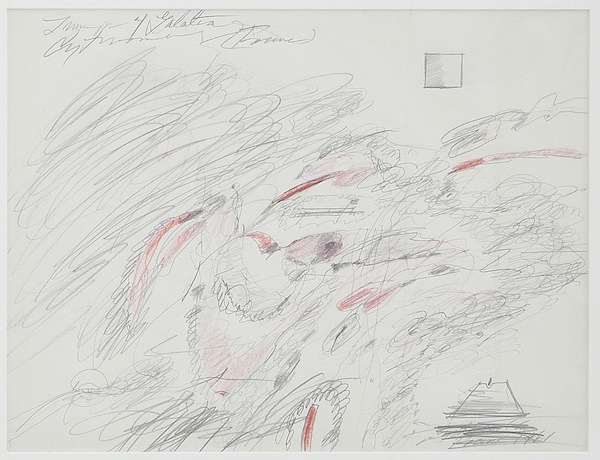

Consider a reductive piece, Triumph of Galatea:

Cy Twombly, Triumph of Galatea, 1961, colored pencil on paper, 10 1/2 x 13 3/4 in., Sonnabend Collection, New York, © Cy Twombly Foundation

Certain recognizable elements persist, despite Twombly's attempts to overwhelm them with the shuddering disruptions of his scribbles. This is distinct from Pollock's or Rothko's pure abstraction. Twombly isn't eliminating the ordinary means of representation. He is, however, trying to separate them from what they represent, to produce pure line, shape, color, and composition; not in the simplified sense of an Albers, but with the complexity of ordinary picture-making. He is attempting to isolate representational means from representation itself, without reducing the complexity of the visual system. This is a logical extension of his wartime work as a cryptographer, which after all involves unlinking language and meaning.

As the foreground of representation recedes, Twombly discovers other properties of picture-making, chiefly the physicality of the act, a topic we discussed previously. Once his lines cease to represent images, their own creation comes to dominate what they express.

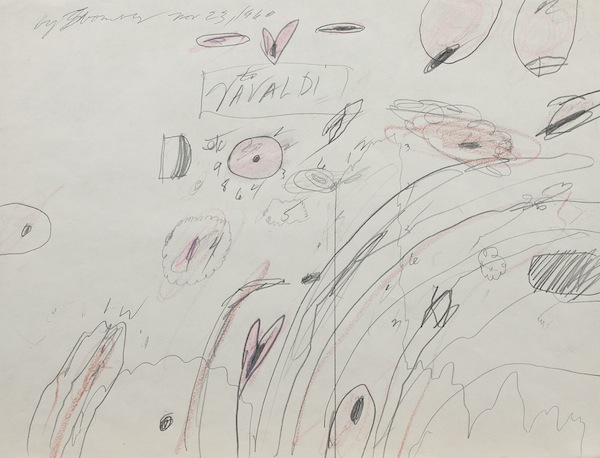

Cy Twombly, Untitled (to Vivaldi), 1960, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 10 1/2 x 13 3/4 in., Sonnabend Collection, New York, © Cy Twombly Foundation

Here we see various moods of line making -- some lines are tight, anxious gestures starting in the fingers and ending at the wrist. Others are swoops of the arm with the elbow locked. Cutting himself off from the world, Twombly is left with the boundaries of his body as the limit of his subject. But the interior of his subject is his mind -- his passages of lines link up into a composition which resembles the disconnected memories we are told flash across the brain of a dying man. Twombly cannot scourge his idiom without scourging himself. He is seeking a deep structure of composition, something essential about how our minds understand the populated picture plane, prior to perception of the external world.

The reductive work leads Twombly down to the bedrock of sight, where line, color, and composition float in cartesian solitude, waiting for a world to latch onto.

From this point of absolute minimalism, Twombly starts out fresh. Physicists stake a claim about the Big Bang: that, given these few initial conditions, it could have gone any number of ways. The proton might have weighed more, or less; the forces might have been distributed otherwise. Twombly, acting as a human particle accelerator, manufactures his own Big Bang. He discovers the few initial conditions for visual cognition. And then he says -- "Screw all of you, I'm starting the universe again with my own preferred proton mass, my own preferred distribution of forces." It will not look like our own universe -- it is his alone. These are the constructive works.

Most exciting among them, I think, is Untitled, 1969:

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1969, gouache and wax crayon on paper, 30 x 39 3⁄4 in., Sonnabend Collection, New York, © Cy Twombly Foundation

The tension of the skeletal muscles has dissolved in his arm. He no longer agonizes: How much? How little? He has reached a point of This, only this. He is like a man who closes his eyes on a windy day, and lets the light rain fall upon him. He has moved into a flow of effortless motion, which starts far beyond one end of his paper and ends far beyond the other. This is a record of communion with an alien cosmos.

There is weather in his cosmos:

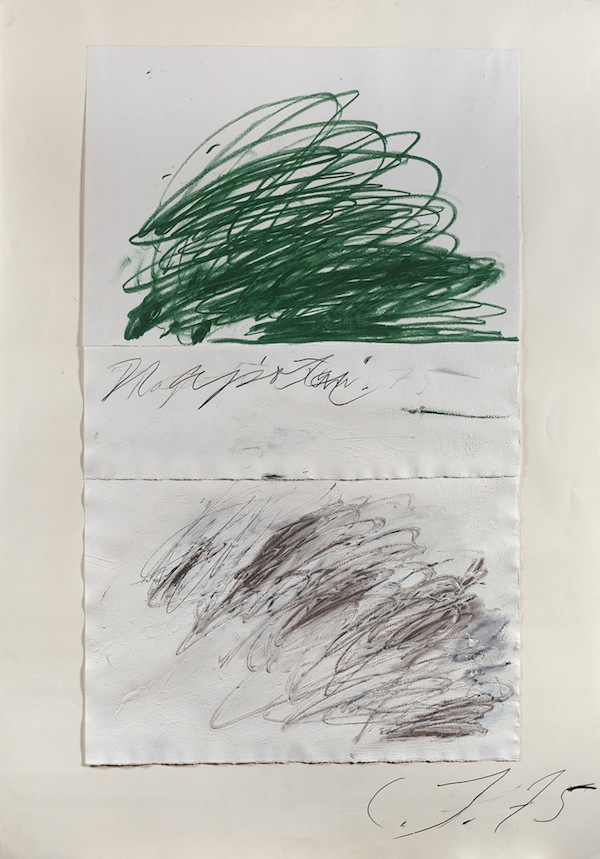

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1975, tempera, pencil, and pastel on paper, 31 1/2 x 19 1/2 in., Sonnabend Collection, New York, © Cy Twombly Foundation

Twin storms are recorded here, frenzied storms. The gesture remains loose, as it does in all the late work, but the ambient energy is high. The marks are much more confident than they were in the earlier pieces, when he didn't know where he was going. Here he has arrived, and uses his reconstructed visual system to make a picture with the guileless trust in his means he could not embrace for classical representation.

Twombly starts out difficult, and he ends difficult. At a glance, his work looks like the scribbling of a child. His excavation of the mechanism of representation fundamentally links his work with the first drawing attempts of a child. An adult man, he strips his brain down to the infantile basics, seeking to make sense of the concept of drawing. We don't need to like what he does to benefit from it. If we stand with it for a while, and wait for the twinge of resonance, what unfolds before us is the vast inland of an individual mind, and a skeleton key to the cipher of how sight becomes drawing.

Eykyn Maclean, Cy Twombly: Works from the Sonnabend Collection, until May 19th, 23 East 67th Street New York NY 10065