If you're in New York and have a spare afternoon on your hands, consider dropping by the German Consulate at Turtle Bay and spending some time with Simon Dinnerstein's masterpiece, The Fulbright Triptych (1971-74, oil on panel, approx. 7'x14').

I am very partial to the grid, in its regular and irregular forms, as modes of structuring art. This structuring occurs naturally in music, but also less intuitively across other art forms: Sol LeWitt does it, and so does Dante. Where the grid appears in a more narrative art form, like literature, it partially displaces the narrative with its own internal geometrical demands. Is there any pressing reason for Dante to end the 34th, 67th, and 100th cantos of The Divine Comedy with the words: "The stars"? Not especially, except that his poem is a grid, and answers to the resonances of the grid.

Apart from its structural delights, the grid has a human dimension which appeals to me. It speaks of the yearning for completeness. He who begins a grid wishes to say everything there is to say about a subject (as Lewitt does in his apparently exhaustive Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes). A linear or braided narrative may twist and turn, it may have holes obvious or hidden. But a regular grid says, "This is all of it; I have discovered all, and presented all." The geometer is by nature a completist, and represents one idol of the artist, in the artist's guise as one who seeks to know.

It is in this context that I approach The Fulbright Triptych.

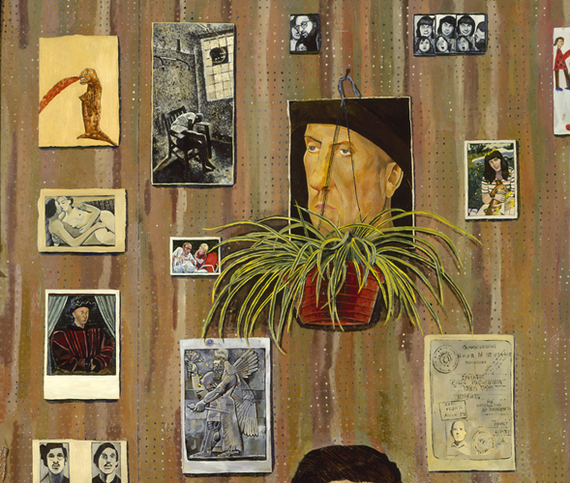

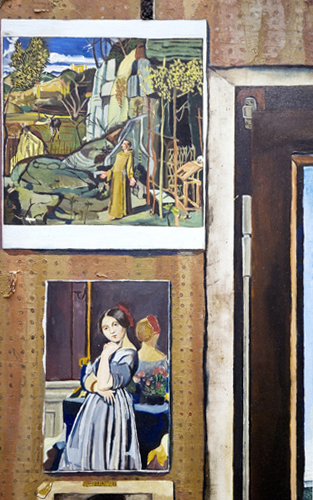

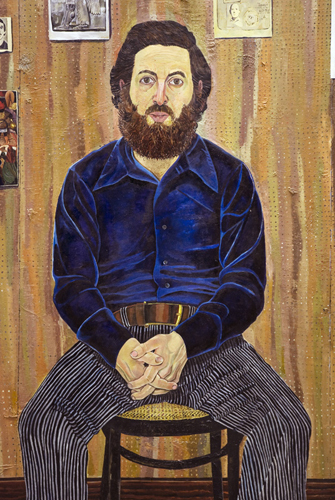

Painted in an appealingly straightforward, outline-oriented American realist style, the enormous triptych depicts the young Dinnerstein on the right, and his wife and infant daughter on the left. In the center is a printmaker's work table, and out the windows a town. This rigid composition, reminiscent of the strangely static architecture and figures of early Renaissance paintings, serves as the pictorial anchor for an irregular grid, consisting in pictures posted to the wall behind the sitters.

These pictures, to me, represent an exploded view of the mind of Dinnerstein. He is surrounded by images of significance to him as an artist and as a man -- Sumerian sculptures, iconic paintings by famous artists, unexplained personal photographs and correspondence, anonymous cheesecake postcards.

There are drawings and writing by children, especially on the left, where his perception of his wife, and her self-perception as a mother and a teacher, cluster.

The images are not presented straight or flat. The specifics of their state at the moment of depiction are included. They have torn edges, dog-ears, water stains, fading and discoloration. More profoundly, they diverge from their original referents. There are distortions, elisions and errors.

These reflect Dinnerstein's own cognition. The source images are presented as parsed by his mind. The digestion of the world by the artist is apparent throughout the composition, but foregrounded especially in the strange collection of objects tacked to the wall. They started life as images, images created by a hundred hands and cameras, and were bound by matter, which decayed, and then became ideas again in the mind of their painter.

This is the irregular grid of The Fulbright Triptych. The regular grid makes its ambition clear: It means to cover everything. The irregular grid admits failure from the start. It appears repeatedly, for instance, in the cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky -- idiosyncratic collections of art prints and objects appear in Solaris, The Mirror and Stalker. The irregular grid is like an extended hand, grasping at a torrent of images, each meaningful in its moment, and most of them lost in the end. The creator of the irregular grid has a strong sense of tragedy. He recognizes that his ambition is doomed, that completeness is outside the scope of the fallible mind, and perhaps of the nature of systems themselves.

Dinnerstein's grid is a tragic grid. It has the poignancy of the packrat: He does not want to lose a single slip of memory. And yet, he is artist enough to recognize that he cannot keep all things, and even if he could, there isn't room enough in life to go on looking at all of them again, and loving them properly. So he loves each thing one more time, as he did the first time he saw it, and then he moves on.

We cannot know if he, as a human being, understands the awful burden of his desires, but as an artist, he certainly understands. Look at his self-portrait:

His eyelids are reddened and his eyes stare vacantly in different directions. He tries to dress and sit with hipness and machismo, but his shoulders slump. As a character in the narrative of his painting, he answers to the contingent pressures of being a young man responsible for his part of starting a family. But as a character in the grid of his painting, he answers to the essential pressures of the mind which finds itself exceeded by the contents of reality. Both of these are good stories, but they take a lot of work to tell, especially the second one. Dinnerstein spent three years telling these stories together. Nobody else did; he did. It is a strange and marvelous thing to behold.

_____

Simon Dinnerstein

The Fulbright Triptych

on display at the German Consulate.

871 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017

9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

Through March 31, 2014