I was talking with Janice Nowinski about her painting, "Nude with Red Background," and something about it reminded me of a principle I learned in a technical course on television broadcasting I took in 1992; for all I know, the principle involved has changed by now.

The principle was this: The brightness of any point on a television screen is defined in a scale called IRE. Analogue broadcast television operates in a range from 7.5 IRE (black) to 100 IRE (white). If you go outside 7.5 to 100, you get problems. Moreover, it is important to include at least a little bit of the extremes in each frame, to assist in broadcaster calibration. If they can't see some 100 on their scope, they might pump up your image brightness until your 80 reads at 100, and your show won't look how you wanted it to look.

So we were instructed, when shooting night scenes, to put in a dot of bright light somewhere -- a streetlight, a candle, a match. Now here is Nowinski's painting.

Janice Nowinski, "Nude with Red Background," 20"x16," oil on canvas, 2013

It's a very dim scene, and its colors are mostly in the brown-red-pink range. But like any good television producer, Nowinski has pegged a little bit of her composition to 100 IRE -- that white cloth or towel the nude is holding. And it's fairly blue, in contrast with the rest of the composition.

Studying this painting, we find that the television principle of hitting the entire range of values has a counterpart in our own minds. Imagine the painting without that towel. We wouldn't know if its world could hold brightness -- it might simply be a dark world. In such a case, the scene on view would not be a scene from the world we know. Likewise the towel's touch of blue tells us this painting does not exist in a red world, but in a world with a full spectrum -- our own world.

That dab of towel, almost illegible, converts this painting from a fantasy painting to a reality painting. It allows us to trust the image, and because we trust it, we take it seriously. We seek out and find the pathos of the figure's hunched shoulders, the weight of her ass, the unselfconsciousness of her gesture -- drying herself or whatever it is she's doing.

Nowinski was a little perplexed when, pacing around her studio, I invoked the esoterica of IRE. She had never heard of it, and didn't think about the towel that way. She was open to the idea, but it really wasn't where she was coming from. That's fine, analysis comes after. What comes before is also important here -- Nowinski works, at the ground level, moment by moment, through artistic intuition. She works on her paintings forever: adjusting, wiping out, overpainting, pausing, reflecting, stopping for long periods, returning and revising. She feels her way through the dark until the illumination strikes her, and she finds that she has arrived at last.

The thing that strikes me most intensely about Nowinski's work is how much I trust it. Pleasingly, it turns out that I also trust her method. Her method is a good bullshit filter, and her work seems to me to be stingy with the bullshit too.

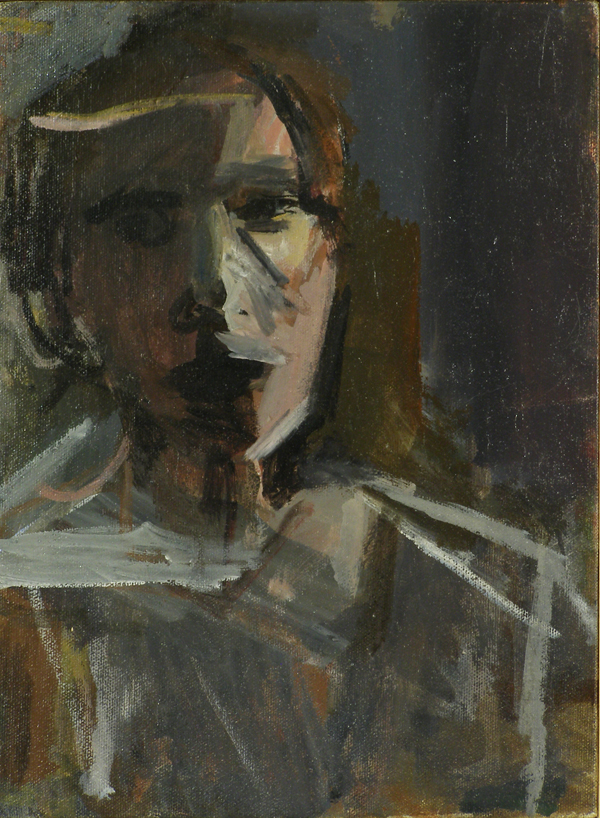

Janice Nowinski, "Portrait of a Man in the Studio," 14"x11," oil on canvas, 2013

Painting hit a zenith of artfulness in the Academic schools of the mid-to-late 19th century. Absolutely brilliant techniques were codified and made teachable, and an unprecedented number of artists emerged who could paint breathtakingly better than anyone you ever saw. These techniques were like the chariot of the sun, and the artists who used them, an army of Phaetons. Phaeton did not have the wisdom or the might to steer the chariot of the sun. The Academic painters, by and large, lacked the intellectual, psychological and moral insight -- and the sheer creativity -- to correctly use their awesome tools. Their work degenerated into a cultish technique-worship. The movement fell into disrepute, and the techniques were discredited, abandoned and partially lost. As with so many of the ideas and technologies of the 19th century, the mean level of human aptitude proved unequal to the opportunities offered. Individual geniuses were ready, but humanity on the whole was not. It still isn't.

There are many reasons for the decline of figurative painting over the century that followed, but the implosion of Academicism into decadence lends its own flavor to the evolution of the issue. The glory of Academic technique, once discredited, discredits the very creation of illusion. The revelation that such seeming truthfulness of image can be divorced from truth of content leaves in its wake a paranoia about the well-crafted image. The mind loses its ability to find either rest or invigoration in the masterfully executed and the beautiful. Mastery and beauty most of all should have been the tools of the great truth-tellers, but they turned out to have been infested with fetishists and liars.

Much as those who wrote the doctrines of 20th century art rebelled against the figurative, they could not be rid of it. They mislocalized their enemy. They thought their struggle was against history. But it was not against history, it was against neurology. The human brain itself has dedicated hardware for seeing the face and the body. When this hardware is consistently not put to use in a culture's art, the art and the culture engage in a battle. The art loses first, and the culture second.

After going on 150 years of savage pitched battle, two irreducible propositions have emerged:

1. The figure must be addressed.

2. Illusion may be the end point, but it remains invalidated as the starting point.

From the interaction of these two, artists like Nowinski emerge. She is by no means the only one of her kind, although in her field, she is very good. These artists answer to the urgent personal version of the proposition: "I know I need to paint the figure, but what can I trust?"

Janice Nowinski, "Paul," 42"x36," oil on linen, 2009

I start from a place different from Nowinski's, and do not have the same trust issues. But I have a lot of empathy for the act of reconciliation she is performing in her work. As in the case of Twombly, I believe that we see in her work not a style, but the underpinnings of style. She has peeled away everything that can still be peeled away, and she is building images of people out of the meat and bones of visual cognition. She makes herself rigorously available to doubt, error and becoming lost. In this way, she awakens herself and forces each movement of her brush on the canvas to be a conscious choice. Her bare minimalism allows the creation of an image with only the scantiest trappings of illusion. It's not much of an image, but it's even less of an illusion.

Janice Nowinski, "Reclining Nude with Long Black Hair II," 9"x12," oil on board, 2013

By this means, she confronts not only the 20th century, but the 19th and all the centuries before; she embraces both her human and her cultural inheritance. She acknowledges not only the necessity, but the failure of the painted figure. In recognizing both, she contributes to the rehabilitation of the things we know we need. She helps to strain out old poisons and discover a language of trustworthy images. This is a good place to start.

Janice Nowinski, "Self Portrait," 12"x19," oil on canvas, 2009

----

Janice Nowinski -- Recent Paintings

October 10 - November 3, 2013

John Davis Gallery

Carriage House, Third Floor

362 1/2 Warren Street, Hudson, New York, 12534

opening reception Saturday, October 12, 6-8 pm

Hours: Thursdays through Mondays, 11 - 5 pm and by appointment

All images courtesy the artist.