Last week the UN moved closer to deploying troops to Northern Mali in a late attempt to remove al-Qaeda from governing a country twice the size of France. African leaders lobbied for the resolution, authorizing 3,300 troops to deploy some time in the third quarter of 2013. Why the UN is authorizing troops to deploy nine months from now raises the question of why it is bothering to deploy them at all, but it also begs the question of why Africa has not yet organized its own force to attempt to take Mali back, given their maturing security institutions and the regional stakes at hand.

The UN resolution places responsibility for rebuilding Mali's army in the hands of European and UN military advisers, while other African forces prepare to bolster the Malian army. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon addressed some of the implied difficulties of the UN plan subsequent to its announcement, stating, "I am profoundly aware that if military intervention in the north [of Mali] is not well conceived and executed, and it could worsen an already fragile humanitarian situation..." He appeared to be referring to the findings of a leaked UN report outlining a potential refugee crisis after fighting begins.

Regardless of the characteristics of the future counterinsurgency operation in Mali, the act of obtaining support from the EU and the UN is part of Africa's traditional reliance on Western liberalism and post-colonial obligations. The challenges inherent in the Mali case are an excellent example of whether this historical practice should continue. Considerable academic analysis of UN intervention suggests that involving a third party in attempting to deescalate conflict can have negative impacts: imposing peace negotiations can be exploited by warring parties as a stalling tactic, for instance, and the presence of humanitarian intervention designed to stabilize a population may actually prolong the effects of war.

Well-intentioned international institutions' single-minded focus on peace and stability tends to be myopic in attempts to ensure the future security of a host nation. The UN's Charter, which establishes it as a global peacekeeping organization, in essence relies on tactics that in practice can have little meaningful leverage (e.g. threats of sanctions, shaming violent groups, or manipulating the international audience through the use of the media). Research shows that the longer foreign troops remain, the longer it will take to achieve outright victory. In any event, it is questionable if, at this late hour, and with so few troops, the UN will succeed.

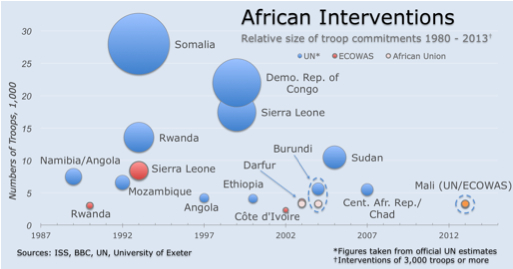

Other institutions such as the African Union (AU) are better placed to act on behalf of Mali. Ironically, the AU uses the same language in its charter as the UN (Chapter VIII of the Constitutive Act) to maintain stability on the African continent. The AU is allowed to intervene in the affairs of a member nation in "grave circumstances". This is primarily used in response to human atrocities, but extends to internal political instability as well. The AU is constrained by reluctance to engage in forceful intervention - as seen in Darfur in 2003 and more recently in Libya - however it remains active throughout the continent.

Now may be the perfect time for the AU to become more independent from other international institutions and become even more active in helping to resolve Africa's problems. With the EU weakened economically and the U.S. fatigued by its own economic challenges and the past decade of failed intervention in foreign conflicts, there is a palpable sense of reluctance among major powers to intervene in African conflicts.

The U.S. presidential debates in November outlined the hypothetical importance to the U.S. of terrorism in the Sahel, but America only promised logistical and intelligence support for military operations as the conflict progresses. Given that Mali is the first state to be run by al-Qaeda, and that it took control of Mali unopposed, America's hands-off attitude is a genuine mystery. As a model for taking power in other failed or failing states, Mali should by all rights have been perceived by the U.S. as a firewall for the future.

Contemporary geopolitical realities in Africa reflect the same vulnerability faced in the post-colonial environment at the end of World War II, which initially gave rise to indigenous collective security regimes. The isolation of some African states soon combined with competitive superpower meddling in African affairs, prompting the need for regional security cooperation. The rising importance of raw materials meant that African nations could rely on aid during political crises in the 1980s and 1990s, but Western benefactors have now refocused their priorities on issues higher up in their own hierarchy of needs.

To maintain their focus on retaining domestic stability, troubled African nations will therefore need to transfer responsibility for regional security to transnational organizations and institutions that are African, not foreign. Given the rapid pace of growth and rising prosperity in many parts of Africa, funds that were previously unavailable to support this endeavor should now be more easily generated.

The AU's "responsibility to protect" concept provides the legal basis for military intervention to preempt regional catastrophes, and was the predicate for successful intervention in Burundi in 2003 and Kenya in 2008. These actions were modest successes against domestic civil unrest, but were noteworthy precedents for obligatory commitment to engage in peacekeeping operations. The stabilization of Somalia in the early 1990s illustrated that complex reciprocal legal commitments exist for collective regional security institutions to function properly. Burundi's 4,000 troops deployed to Somalia under AMISOM were the result of previous agreements made in exchange for the stabilization of Burundi's government.

However, the AU suffers from the same form of institutional reluctance that prevents the UN from passing resolutions for large troop commitments. Darfur is the oft-cited example of failure that prevents progress in this area. The AU could take a lesson from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a regional organization with a history of authorizing actions to stabilize parts of Africa, such as Somalia and Sudan. In fact, ECOWAS already concluded its own agreement to aid Mali with 3,300 troops in 2013. Whatever trepidation the organization may have, 13 of 15 members have pledged to deploy troops to support the Malian army.

Unless the Malian junta in the South concludes an agreement with the Islamists and Tuareg rebels in the north (which seems unlikely), some form of foreign intervention will deploy to Northern Mali next year. The composition of that force will likely be majority African, supported by European military instructors and American intelligence. Success is harder to predict -- given the expansive terrain. quality of military personnel on both sides, and length of time required to effectively target Islamist strongholds -- but is likely to prove elusive.

The larger issue brought to light by the Malian conflict is how best to achieve African integration with African institutions leading the way. Assuming that the remainder of this decade sees continued economic and political distress in the U.S. and Europe, African nations will be forced to address their regional disputes without resourceful allies to act as referee. Africa has established an effective network of security regimes to safeguard territorial sovereignty and target threats. The effectiveness of these institutions is debatable, but the need for them is not. Whether African leaders like it or not, they must find a way to marshal their resources to solve their own problems. Mali will be the test case under the new paradigm of failed or failing states succumbing to political change under the rule of Islamic extremists.

*Daniel Wagner is CEO of Country Risk Solutions, a cross-border risk management consulting firm based in Connecticut, and author of the book "Managing Country Risk". John Margeson is a research analyst with CRS based in New York.