As we recognize that American sports and culture do not represent a "post-racial society" after all, it's important to look back at the '60s, the era where there was perhaps the greatest change in the relationship between African-Americans and White America. This article is the third in my series about the meaning of Muhammad Ali in America and the world. Furthermore, Ali's embrace of Islam resonates in light of today's confrontations.

You may access the other parts of this piece, as well as my other articles here.

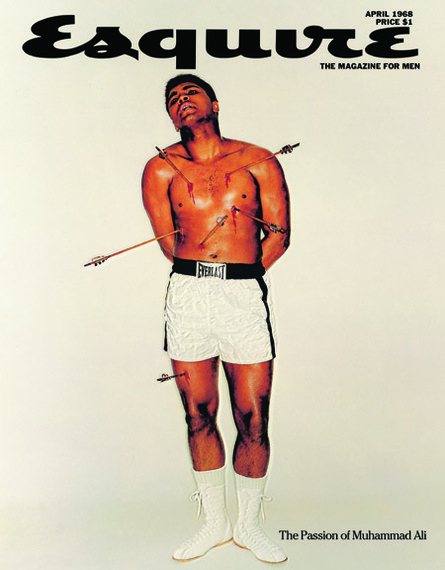

George Lois for Esquire Magazine

After claiming his belt, Ali traveled to Africa, a trip that Malcolm X had planned for the boxer. Yet on this trip, Ali and X became far detached from the fraternal relationship that they shared only a few months prior. Malcolm had broken off from the Nation of Islam, expecting his two favorite prodiges, Cassius Clay and Louis Farrakhan, to follow. In order to prevent Clay from joining Malcolm's faction Elijah Muhammad decided to honor the boxer with a Muslim name. Despite the tension between Ali and Malcolm, the trip commenced anyway. Thousands upon thousands of people came out to witness the new heavyweight champion, and because of this, Ali began to recognize that he was more than just an American boxer. Louis Farrakhan noted that Muhammad Ali held a particularly special meaning in the Muslim world; not just anyone was meant to have claim to such a praise-worthy title. He did not yet know what he meant to the world, but he realized he was important and that his actions would speak loudly.

Within only a few months after the conclusion of the trip, Malcolm X was assassinated in Harlem, allegedly by order of Elijah Muhammad. Even though their relationship had crumbled, Ali felt tremendous guilt about abandoning Malcolm. As he would later go on to reflect: "Turning my back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes I regret most in my life." Despite his feelings of guilt, Ali would stand firmly with the Nation of Islam. The controversy around the name of Muhammad Ali would only grow.

After his first defeat of Sonny Liston in Miami, many were not entirely convinced that Ali was worthy of the heavyweight belt and still pictured the Bear as the preeminent fighter. Thus, the two most famous boxers in the world met together for a second fight in Androscoggin Bank Colisee in Lewiston, Maine, exactly fifteen months after their first match. Unbelievably, the results from Ali vs. Liston II, as the press dubbed it, were even more staggering than their first encounter. After only a little more than thirty seconds from the starting bell, Ali landed a left jab to Liston's face, sending the challenger to the ground. Liston would not get up before the mandatory ten count. Ali defeated Sonny Liston after only forty-eight seconds. Despite the fact that many critics postulated that the Bear threw the fight to pay off mob debts, there were no more calls for a rematch. Soon Muhammad Ali would begin the biggest fight of his life, a fight against America's government and much of her public, a fight outside of the ring.

In early 1966, Muhammad Ali received a phone call from the Associated Press inquiring about his reaction to the Louisville draft board's changing his draft status to 1A, meaning that Ali would be available for unrestricted military service. According to Robert Lipsyte, sportswriter for the New York Times, the boxer's immediate reaction was utter fury, followed by the question: "Why me, the heavyweight champion of the world?" Ali proclaimed this in one of dozens of television interviews that began after the change to 1A status. When a reporter asked how Ali felt about going to Vietnam to fight, the boxer famously responded: "I ain't got no quarrel with them Vietcong." With all of Ali's great boxing opponents exhausted, Lipsyte and his fellow sports reporters began to realize that a new story had been born.

On April 28, 1967, Muhammad Ali walked into an army induction center in Houston, Texas. There he would inform the draft board that he was refusing to take the army oath, saying he was exempt because of his ministership in the Nation of Islam. Ali had no interest in once again serving his country and returning with a medal on his chest only to meet the same injustices that he faced for his entire life. He left the induction center to the applause of many of his fans, who were cheering: "If he don't go, we don't go." What Ali had just done created a tremendous problem for White America. Blacks, proportionally, were dying in far greater numbers than whites in Vietnam, and already by 1966, the majority of African Americans opposed the war. The profound effect of Muhammad Ali, in particular, to refuse the call to service was that it became acceptable for other young Americans to reject the summons to Vietnam. If the most masculine man alive, the heavyweight champion of the world, refused his induction, then what was stopping anyone else from doing the same? A man could now rebuff his "call of duty" and still be a man. In the words of Gerald Early, a cultural critic and professor at Washington University in St. Louis:

When he refused, I felt something greater than pride: I felt as though my honor as a black boy had been defended, my honor as a human being... The day that Ali refused the draft, I cried in my room. I cried for him and for myself, for my future and for his, for all our black possibilities.

But much of White America, especially on the right of the political spectrum, sought to demonize the boxer and his stance on the war.

One of the first steps in shutting down Muhammad Ali was denying him the right to fight. Each state had a boxing commission, attached to the larger state-wide bureaucracy. On April 28, 1967, the same day Ali refused to be inducted, the New York State boxing commission indefinitely suspended his license to box and stripped him of the title of heavyweight champion of the world. And soon after, every other state would follow suit, leaving the now titleless Muhammad Ali, the world's greatest boxer, unable to fight within the United States. Less than eight weeks after losing his championship belt and his right to box, on June 20, 1967, an all-white jury found Ali guilty of draft evasion after less than twenty minutes of deliberation. They gave him the maximum penalty of five years in prison, accompanied by a fine of five thousand dollars. Muhammad Ali was willing to accept a five year prison sentence, just as Elijah Muhammad had for his draft evasion. He was also willing to lose millions of dollars in order to support the conviction that Allah prohibited Muslims from going to war.

Ali's draft refusal caused a profound split between those who saw Ali as a hero to be emulated, and those who pictured him as a draft-dodging villain. Across the country both African-Americans and whites alike greatly disapproved of Ali's decision. A proclamation from the senate of Ali's home state of Kentucky read: "His attitude brings discredit to all loyal Kentuckians and to the names of the thousands who gave their lives for this country during his lifetime." In addition, other black celebrities aligned with the NAACP, such as Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson and former heavyweight champion of the world Joe Louis, condemned Ali. And although the convictions of members of America's black community were not always as strong or negative as those of Robinson or Louis, many African Americans were perplexed by Muhammad Ali's refusal to fight in the Vietnam War and wondered why he would be willing to endure such trouble and financial burdens just based on principle. Ali was far from free of scrutiny when it came to the liberal media as well. On a 1968 television appearance on the Eamonn Andrews Show, David Susskind, a well-respected liberal television personality, brutally challenged the most famous boxer in the world:

I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man. He's a disgrace to his country, his race, and what he laughingly describes as his profession. He is a convicted felon of the United States. He has been found guilty. He is out on bail. He will inevitably go to prison, as well he should. He's a simplistic fool and a pawn.

While many saw Ali's actions as traitorous, millions of Americans and people throughout the world applauded his stance and his bravery. Sonia Sanchez, a poet and Civil Rights activist, remarked on the boxer's impact: "[When he refused his induction, it] was still a time when hardly any well-known people were resisting the draft. The heavyweight champion, a magic man, taking his fight out of the ring into the arena of politics and standing firm. The message was sent." While the notion of such a high profile figure rejecting the call to Vietnam was liberating, as it was to both Sanchez and Early, some of Ali's other supporters found the danger in his situation. Famed philosopher and pacifist Bertrand Russell wrote to Ali:

In the coming months, there is no doubt that the men who rule Washington will try to damage you in every way open to them, but I am sure you know that you spoke for your people and the oppressed everywhere in the courageous defiance of American power. They will try to break you because you are a symbol of a force they are unable to destroy, namely, the aroused consciousness of a people determined no longer to be butchered and debased with fear and oppression.

And even though Ali had just begun his fight against the army, it was not the first instance in which others sought to demonize him and the religious and political ideologies that he stood for.

You may access the other parts of this piece, as well as my other articles here.