This year, politics consumed the culture and attack ads became common currency. That makes it hard for the creative class to decide where to reside: Make work that engages the white hot topical moment or run for the hills seeking wisdom above the fray. Against long odds, the cultural highlights of 2012 managed to examine human nature with considerable nuance even as the background noise threaten to grow deafening.

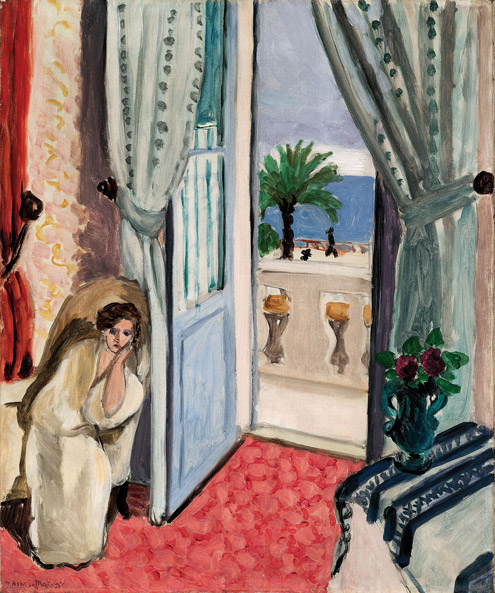

Henri Matisse: Interior at Nice (1919). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bring Up The Bodies: Hilary Mantel. Don't let praise turn you off from the most absorbing book of the year. Thomas Cromwell outflanks his rivals with a single-minded brilliance that's chilling yet utterly compelling. The suspense remains tangible centuries after the fact, thanks to Mantel's engrossing portrayal of backroom strategies, candlelit interiors and finely drawn court characters. You're left with a historic examination of ambition that manages to be a benchmark of our time. The trilogy's finale cannot come soon enough.

Henri Matisse: In Search of True Painting. Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition is even better as it reverberates in your memory. We witness considerations of a theme -- from Notre Dame to Nice, models to still lifes -- that provide varying formal clues to the master's brilliance. The results are both wide ranging and specific, different versions of the same subject don't simply offer evidence of genius they reveal the decisions behind how it came to be.

At Last: Edward St. Aubyn. The finale of the Patrick Melrose novels is so perfectly pitched in its social observation, so exacting in its humor that it can rightly be compared to any satirical English novel in memory. But it's more than satire. As Patrick achieves a resigned sense of peace, we revel in his harrowing lessons well-learned. His emotional tumult provided a catharsis to readers who are privileged to witness his transformation.

JMW Turner: Sea and Clouds (c. 1820-30). Tate Britain.

Vija Celmins' room at the Tate Britain was precise in its loveliness, as you would expect. The revelation, however, came in an adjacent gallery, where she selected Turner works on paper. His sketches of seascapes and shorelines possess the untroubled assurance that comes from expert virtuosity. Exquisite.

It was a year of partisan passions in such opposition that we were forced to question what we thought we knew. Nate Silver became the symbol of analytical reason in the age of cable TV's blind assertions. There were lighter moments: Nick Paumgarten's winning New Yorker piece about being a Deadhead was a hysterical portrait irrational fandom -- even for those of us who are jam band-averse. We prefer the sound of Trust's misanthropic dance music, which was a highlight of our annual pilgrimage to the madness at South by Southwest.

Some backward glances that felt surprisingly immediate. The Afghan Whigs delivered a completely unsentimental reunion that was as bracing and depressing as it was when we were in college. While Prestel's beautiful book Caspar David Friedrich got as near to the paint as possible. It was luxuriant, just what you want from a book the size of a record player. The xx, followed their debut with the enchanting Coexist. Withholding in the best sense--it's demure, tender and vulnerable, with a finely wrought emotional fragility, all delivered neatly in just over half an hour.

Let's leave principled compromise to the politicians -- there's no shame in that. But there remains an ongoing pursuit of singular vision. That's why we need artists. Good ones bring us closer to how we know ourselves. Great ones bring us closer still.