"Don't blame me," argues Alan Greenspan in a piece of historical revisionism that would have embarrassed Kurt Waldheim. Greenspan offered up a Panglossian analysis in today's Wall Street Journal that goes something like this:

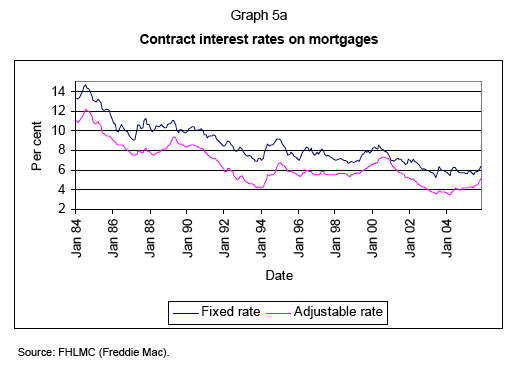

The rise in housing prices was tied to the decline in the rates for long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. Historically there has been a strong historic correlation between the fed-funds rate and rates for long-term, fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs). "Between 2002 and 2005, however, the correlation diminished to insignificance," writes Greenspan. There was no correlation, ergo the Federal Reserve did not inflate the housing bubble.

Here's the truth.

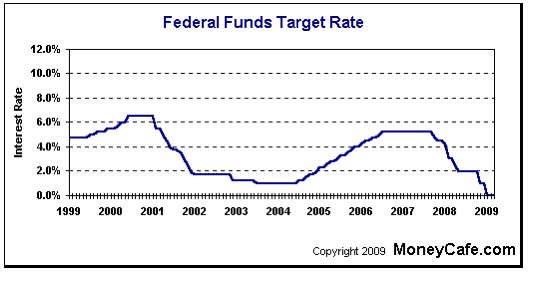

In the years following the end of the last recession, which ended in November 2001, Greenspan lowered rates relentlessly in order to prime the economy for the 2004 election. By mid-2003, the fed funds rate was one percent, a 45-year low. Mortgage rates for both FRMs and adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) fell dramatically, but rates on ARMs fell more. And this is a critical point. By early 2004 the rate difference between FRMs and ARMs was two percent, the highest it had been in 10 years. In other words, if you had a $120,000 mortgage, your monthly payments would have been $200 less under an ARM.

The bigger the rate difference, the more likely homeowners are to elect to finance with an ARM.

But in prior years when homeowners flocked to ARMs, interest rates were high, so the likelihood that homeowners would face sticker shock at the time of a rate reset, or the likelihood that home prices had been inflated by low interest rates, was fairly low. In early 2004, when 5-year ARMs hovered around four percent, compared to FRMs at six percent, the refinancing risk associated with an ARM was much greater.

And it was precisely at this point, going into an election year, when Greenspan threw gasoline on the fire, encouraging homeowners to try ARMs. "Greenspan says ARMs might be better deal," was the USA Today headline on February 24, 2004. "Alan Greenspan said Monday that Americans' preference for long-term, fixed-rate mortgages means many are paying more than necessary for their homes and suggested consumers would benefit if lenders offered more alternatives," the paper reported.

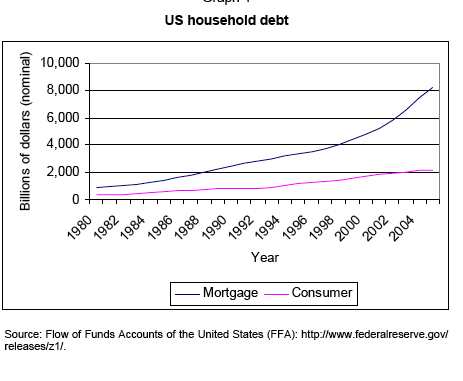

Bear in mind, that Greenspan knew perfectly well that homeowners' capacity to take on incremental debt was already becoming strained.

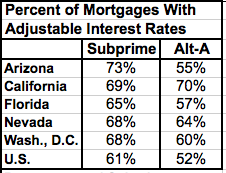

When Greenspan spoke, people listened. So by March 2005 the percentage of homeowners taking out adjustable-rate mortgages hit an all-time record, at 36%. In 2001, it was 12%. In 2002, it was 17%.

Moreover, ARMs were concentrated among the riskiest types of mortgages in the riskiest markets, as we see from statistics from the New York Federal Reserve. These are the markets, and the mortgages, that drove the bubble and the financial crisis we face today. (For more details, see, "The Simple Arithmetic of the Mortgage Crisis.")

Of course the housing bubble was not only inflated by low interest rates. It was also driven by fraud and predatory lending, which was allowed to flourish because Alan Greenspan refused to do his job, which was to provide appropriate regulatory oversight on mortgage lenders.

For his CNBC special, "House of Cards," David Faber confronted Greenspan on the issue of subprime mortgages.

DAVID FABER: Alan Greenspan clearly didn't realize the full extent of

the housing bubble in 2005, nor was he aware of the enormous growth in

subprime mortgages, which, by 2005, represented 20 percent of all new

mortgages.

ALAN GREENSPAN: I remember my initial response when a staff member

came up to me and he says, "I don't know if you have seen something like

this." I said, "I don't believe that number." It became a huge

revelation.

DAVID FABER: Really? I mean, I find that somewhat hard to believe.

ALAN GREENSPAN: It is hard to believe, but it was still perceived to

be a small part of the market.

DAVID FABER: Greenspan now says that even if he did know the true

dimensions of the housing bubble back then, he wouldn't have been able to

do much to stop it.

ALAN GREENSPAN: The presumption that you could incrementally defuse a

bubble was a fantasy. Clearly, you cannot defuse these things, unless you

hit them right on the head and break the economy. Essentially, break the

potential profitability that is engendering that sort of stuff.

DAVID FABER: So you're essentially saying there is nothing the Fed

could have done.

ALAN GREENSPAN: To prevent the bubble?

DAVID FABER: Correct.

ALAN GREENSPAN: Yes, we could have. We could have basically clamped

down on the American economy, generated a 10 percent unemployment rate.

And I will guarantee we would not have had a housing boom, stock market

boom or indeed a particularly good economy either.

Greenspan did to Faber what he did to The Wall Street Journal's readers. He threw sand in his face.

ADDENDUM: March 13, 2009, 4:55 pm Some of the comments below have noted that the Fed began raising the fed funds rate prior to the 2004 election, and contend that such actions disprove my point that Greenspan reduced rates in a way that would have helped Bush's reelection prospects. I had assumed that everyone was familiar with the concept of "monetary time lag" defined by one financial dictionary as, "The time between a change in interest rates and when an effect is felt in the economy. A typical lag time is 6 to 12 months." Voters' perceptions of changes in the economy lag further behind actual changes in GDP.

Greenspan kept the fed funds rate at 1% between June 2003 and June 2004, when he raised it to 1.25%. The impact of the increase - in terms of how it would be felt by voters perceptions of the economy, not measured GDP - would have been felt only after the November 2004. The timing of the increases suggests that Greenspan waited so that the impact of the rates would be felt only after the election.