In a 1999 essay, Ernst van de Wetering, professor of art history at the University of Amsterdam and chairman of the Rembrandt Research Project, noted that Rembrandt had painted himself at least 40 times, had etched himself 31 times, and had drawn a handful of self-portraits. Van de Wetering then declared that "This segment of his oeuvre is unique in art history, not only in its scale and the length of time it spans, but also in its regularity."

Van de Wetering's claim is not even close to being correct. The scholar Iris Müller-Westermann observed that Edvard Munch "recorded himself in more than seventy painted works and about twenty graphic self-portraits, as well as in more than one hundred watercolors, drawings, and studies; sometimes year by year, at times monthly or even daily." Munch thus produced more than twice as many images of himself in all media as had his great predecessor. Rembrandt first painted himself at 20, and continued to do so until near the end of his life at 63, but this span of 43 years also falls far short of the 62 years that separated Munch's first self-portrait at age 19 from his last at 81.

Van de Wetering's remarkable error is symptomatic of art scholars' failure to recognize a striking development of the modern era, that I have called personal visual art. Early in his career, Munch was deeply influenced by Hans Jaeger, a charismatic Norwegian philosopher who stressed the importance of self-examination. Munch's belief in self-scrutiny was reinforced when he saw a memorial exhibition of paintings by Vincent van Gogh in Paris in 1891. Munch later wrote of van Gogh that "Fire and embers were his brushes during the few years of his life... I have thought, and wished... to follow in his footsteps. Not to let my flame burn out, and with burning brush, to paint to the very end."

Munch thus became one of the earliest practitioners of personal visual art. Literary scholars have given a name -- confessional poetry -- to the practice, begun by Allen Ginsberg and Robert Lowell in the 1950s, of making poetry out of the poet's life, but art scholars have not noticed that this practice became important much earlier in visual art. Van Gogh and Munch were among the first painters to base their work almost entirely on their own lives, and they have been followed by Frida Kahlo, Francis Bacon, Louise Bourgeois, Joseph Beuys, Bruce Nauman, Tracey Emin, and many others. Like van Gogh, Munch hoped that his careful examination of his face, and his life, would be valuable to others. Thus he reflected that his focus on himself "could... be called egotism. However, I have always thought and felt that my art might be able to help others to clarify their own search for truth."

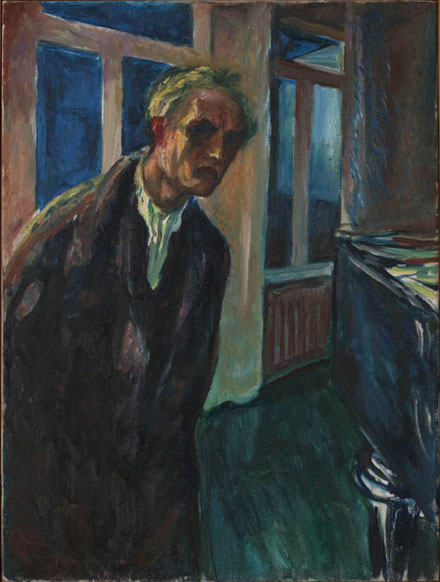

Self-Portrait. The night wanderer. Edvard Munch, 1923-1924, Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

Paris' Centre Pompidou is currently exhibiting more than 100 works by Munch, on loan from Oslo's Munch Museum. The show is an excellent opportunity to see many paintings that do not often travel. In one respect, however, the show does Munch a considerable disservice. At the beginning of the show, the curators tell visitors that Munch "created three quarters of his works after 1900 and died in 1944, the same year as Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky... [T]he present exhibition aims to show that Munch was also a 20th century artist."

That aim is misguided, and the association of Munch with Mondrian and Kandinsky as an artist of the 20th century is foolish. Munch's great contribution to advanced art occurred with the early Symbolist paintings he made in the 1890s. Unlike the great experimental innovators Mondrian and Kandinsky, Munch took no notice of the two great innovations of the early 20th century -- Fauvism and Cubism -- and his art of the 20th century had little if any stylistic or technical impact on younger artists. Like many young conceptual innovators, Munch's art failed to develop after his major early breakthrough. (In sharp contrast to Mondrian and Kandinsky, Munch's only apparent foray into abstraction was in fact an attempt to paint what he actually saw after he suffered a hemorrhage in one of his eyes in 1930.) Vampire (1893) and Puberty (1894-5) open the Pompidou exhibition. These display the innovative combination of line, color, and distortion that made Munch's early work a powerful influence on Expressionism in the 20th century. But for Munch these were the end of something, rather than the beginning. The Pompidou show demonstrates that his later work was less expressive, more decorative, and often repeated the images of his early work without matching its intensity. The nine self-portraits at the Pompidou, that range from 1901 through 1944, are period pieces that make no contact with the rapidly changing art world of the early 20th century. Like Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, Munch appears in these late works as if frozen in psychological time and space. Munch did paint to the end of his life, but his flame had long since burnt out.

Self-Portrait. Between the clock and the bed. Edvard Munch, 1940-1943, Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye runs in Paris through January 9, then moves to Frankfurt for the spring, and to London's Tate Modern for the summer. It provides an opportunity to see works of a great artist that can usually only be seen in Oslo. But it also serves as a cautionary warning to curators not to make inflated claims about the artists they present. As a young artist, Edvard Munch made fundamental innovations, by extending the means of visual representation of anguish and helping to pioneer the practice of personal visual art. These contributions should not be diminished by exaggerated assertions about the significance of his later work.