David Hockney recently touched off a controversy with a poster advertising his new exhibition at London's Royal Academy of Arts that read: "All the works here were made by the artist himself, personally." When the BBC journalist Andrew Marr asked Hockney if the statement was a dig at Damien Hirst, who employs up to 100 craftsmen to fabricate works that Hirst designs, Hockney nodded, and said, "It's a little insulting to craftsmen... I used to point out at art school, you can teach the craft, it's the poetry you can't teach. But now they try to teach the poetry and not the craft."

Hockney's comments created a minor scandal for British journalists, because Hirst has effectively dominated the English art world for nearly two decades, and less than a week later Hockney was forced to backtrack, as the Royal Academy issued a statement on his behalf denying that Hockney had "made any comments which imply criticism of another artist's working practices." Yet Hockney's comments had clearly touched a raw nerve, for the issue of whether paintings should be executed by an artist personally is one that has never been fully resolved in the art world.

One prominent statement on this issue was that of the French philosopher Etienne Gilson, who presented his analysis of the art of painting in the 1955 Andrew Mellon Lectures at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. In considering the essence of painting, Gilson stated that:

The nature of painting is such that the artist who conceives the work is also the one who executes it... Except for tasks of secondary importance that can easily be left to his assistants, it is the painter himself who confers the material and physical existence upon the work he conceives.

For Gilson, unlike poets, novelists, and composers, who were white-collar workers, painters must necessarily work with their hands: "When all is said and done, painters... are related to manual laborers by a deep-rooted affinity that nothing can eliminate." Gilson left no room for doubt: "A painter is the sole and total cause of his work."

Gilson of course knew that many Old Masters used assistants extensively in their studios. So for example Vasari tells us that when Raphael became successful he "was never seen at court without some fifty painters," and John Pope-Hennessy noted that in this phase of his career "Raphael over a large part of his work became an ideator instead of an executant," as he made detailed preparatory drawings for works that would be painted by assistants. But Gilson described such cases as "a master and assistants working together under his direction and responsibility," and discussed several examples in which masters completed works that had been begun by assistants. And we know specific cases in which painters openly acknowledged these arrangements: so for example in 1618 Peter Paul Rubens wrote to a patron that paintings not entirely by his hand "are rated at a much lower price."

It is not necessary to struggle with the question of whether Old Masters took credit for paintings they had never touched, for the evidence on this is unambiguous for more recent times. Etienne Gilson's Mellon Lectures were published in 1958, and the ink was barely dry on his claim that it was the touch of the painter that created the work of art before a flamboyant compatriot of his conspicuously violated that claim. Early in 1960, in Paris, Yves Klein began to create paintings with what he called "living brushes." Nude female models would cover themselves with Klein's patented International Klein Blue paint, then press themselves against large sheets of paper tacked to the wall or spread out on the floor. To emphasize his separation from the physical act of painting, while the models were making the paintings Klein would often wear a tuxedo and white gloves; as he explained,

In this way I stayed clean. I no longer dirtied myself with color, not even the tips of my fingers. The work finished itself there in front of me, under my direction, in absolute collaboration with the model. And I could salute its birth into the tangible world in a dignified manner, dressed in a tuxedo.

The process followed Klein's conception of the artistic process, for he believed that the artist should conceive works of art but not personally produce physical objects, for as he put it, "True painters and poets don't paint and don't write poems."

Andy Warhol, Blue Marilyn (1962) Collection of the Princeton University Art Museum

Andy Warhol may have done more than any other artist of his generation to subvert traditional practices associated with painting. In 1962, he began using silkscreens to make his paintings, and almost overnight he came to be seen as the leader of the controversial new Pop movement. The demand for his work soared, and in 1963 Warhol hired Gerard Malanga as an assistant. In an interview that year, Warhol declared "I think somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me," and in 1965 he told an interviewer that "Gerard does all my paintings." Years later, Warhol denied this, and dismissed his earlier statement as a joke. Yet Malanga has said of the early years, "When the screens were very large, we worked together; otherwise I was left to my own devices." For Warhol, painting by proxy was related to his use of silkscreens, as he famously declared that "The reason I'm painting this way is that I want to be a machine."

Sol LeWitt, installation of Wall Drawing #1111 (2003) Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago

In 1968, Sol LeWitt began making what would become his trademark form of art, works drawn or painted directly onto walls. In 1971, in a published statement about this new genre, he described a complete separation, in which the artist planned the wall drawing, then had it executed entirely by a draftsman. LeWitt went on to make hundreds of plans for wall drawings throughout the remainder of his career, until his death in 2007. He virtually never executed these wall drawings himself, and in most cases he never even saw them. Interestingly, LeWitt went beyond the practices of Klein and Warhol in one intriguing respect, by achieving a kind of productive immortality: his drawings continued to be executed even after his death, in precisely the same manner as they were during his lifetime. So for example one of his drawings was executed on a wall of the new wing of Chicago's Art Institute when the wing was built in 2009, two years after LeWitt's death.

In recent decades it has become commonplace for successful painters to have assistants perform most or all of the labor involved in executing their finished works. Jeff Koons is among these. In 2000, Koons told the critic David Sylvester that he didn't have time to execute his paintings, but that his staff of dozens produced works identical to those he would have made. When Sylvester asked why, unlike Raphael and Rubens, Koons chose not to do any of the actual painting himself, Koons explained that painting would actually interfere with his development as an artist: "My vocabulary isn't just the execution of it; it's also a continued conception of where I want my work to go in another area. So it has more to do with the reality of being able to be in a position where I can continue to grow as much as possible as an artist, instead of being tied down in the execution of the work."

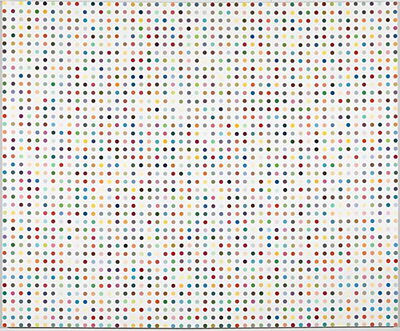

Damien Hirst has defended his practice of using assistants to make his spot paintings, on the grounds that the assistants do better work than he did: "I only ever made five spot paintings.  Personally... I did them on the wrong background, there's the pin-holes in the middle of the spots... Under close scrutiny, you can see the process by which they were made... The best person who ever painted spots for me was Rachel [Howard]. She's brilliant... The best spot painting you can have by me is one painted by Rachel." Hirst also commented that "The dots are boring [to make]. And I love other people." In the same interview, Hirst made a comment about the gridded spot paintings that echoed Warhol: "I want them to look like they've been made by a person trying to paint like a machine."

Personally... I did them on the wrong background, there's the pin-holes in the middle of the spots... Under close scrutiny, you can see the process by which they were made... The best person who ever painted spots for me was Rachel [Howard]. She's brilliant... The best spot painting you can have by me is one painted by Rachel." Hirst also commented that "The dots are boring [to make]. And I love other people." In the same interview, Hirst made a comment about the gridded spot paintings that echoed Warhol: "I want them to look like they've been made by a person trying to paint like a machine."

("Damien Hirst, Anthraquinone-1-Diazonium Chloride(1994), Courtesy of the Tate Collection, London, UK")

We might draw several conclusions from this brief examination of the history of painting by proxy. One is that Etienne Gilson made a fundamental error, by stating that there were immutable rules of art, that could never be violated. In doing this, he failed to recognize the force of the conceptual impulse in 20th-century art. The story of art in the past century is in large part one of young iconoclastic innovators breaking every significant rule, tradition, or convention that they could identify. Gilson was foolish not to anticipate that conceptual artists would find a way to break the rules of painting he published in 1958, and his supposedly immutable rule in fact survived less than two full years.

Gilson's analysis was less perceptive than the earlier reflections of another of his compatriots, the poet Paul Valéry. In 1936, Valéry wrote that,

It sometimes seems to me that the labor of the artist is of a very old-fashioned kind; the artist himself a survival, a craftsman or artisan of a disappearing species, working in his own room, following his own home-made empirical methods, living in untidy intimacy with his tools...Perhaps conditions are changing, and instead of this spectacle of an eccentric individual using whatever comes his way, there will instead be a picture-making laboratory, with its specialist officially clad in white, rubber-gloved, keeping to a precise schedule, armed with strictly appropriate apparatus and instruments, each with its appointed place and exact function... So far, chance has not been eliminated from practice, or mystery from method, inspiration from regular hours; but I do not vouch for the future.

Another conclusion is that it is readily understandable why David Hockney had to withdraw his criticism of Damien Hirst's painting by proxy. For Hockney's criticism applied not only to Hirst, but to one of the most vital trends in the advanced art of the past 50 years. Yves Klein, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Sol LeWitt, Jeff Koons, and Damien Hirst are only the most famous of the painters of recent years who have rarely if ever touched their own canvases. Painting by proxy simply appears too firmly established in the modern canon to challenge successfully. As Warhol succinctly explained in 1966, "In my art work, hand painting would take too long and anyway that's not the age we're living in. Mechanical means are today." More recently, Damien Hirst updated this attitude, observing that "The painter has stopped being this hairy guy with paint all over him. He became a guy in a suit, or a lab coat." Making the touch of the artist irrelevant to the authenticity of a painting is one of the many elements of the conceptual revolutions of the past century which no longer appear reversible.

Image links:

Yves Klein, Large Blue Anthropometry (1960), Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain

Andy Warhol, Blue Marilyn (1962), Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ

Sol LeWitt, Installation of Wall Drawing #1111 (2003), The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL