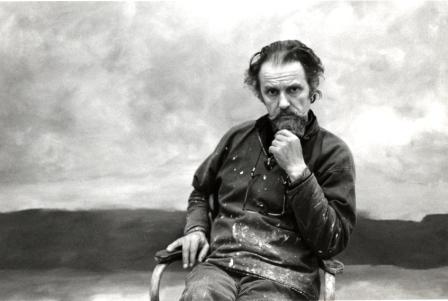

Jon Schueler, 1973, photograph by Magda Salvesen (c) Jon Schueler Estate (in his studio in Mallaig, Scotland)

In 1904, Paul Cézanne wrote to the younger painter Emile Bernard, "I progress very slowly, for nature reveals herself to me in very complex ways; and the progress needed is endless." Two decades earlier, Cézanne's friend Camille Pissarro wrote to his son Lucien, "I will calmly tread the path I have taken, and try to do my best. At bottom, I have only a vague sense of its rightness or wrongness."

Cézanne's letters, and those of Pissarro, are classic portraits of their authors as what I have called experimental artists -- those who seek to present visual perceptions, but lack a clear idea of how to accomplish this, so they work tentatively, by trial and error, dogged all the while by doubt and uncertainty. From a later generation, Jon Schueler's The Sound of Sleat adds another vivid self-portrait of the modern painter as an experimental artist.

In June, 1958, Schueler was living near Paris, during a year in Europe funded by sales from an exhibition of his work at Leo Castelli's new gallery in New York. He wrote in his journal of his frustration:

I am reminded of Picasso, saying "I do not seek, I discover."... He's a lucky man. I like the assurance with which he is able to make that statement. Schueler says, "I do not discover, I seek." That's the story of my painting. An eternal search. I never know precisely what I am looking for. I have faith that it is there, that I shall discover it, that I shall reveal this truth -- but I don't know when it shall be revealed.

Schueler understood the cost of his experimental personality: "I'm always dealing with the unknown and with the mystery, and therefore there is little sense of satisfaction or discovery." Yet he also recognized the benefit: "This is what my freedom is: To be uncertain, questing, wondering. I don't really want certainty there. I want to keep looking."

Schueler had gone to New York in 1951, and there he saw the work of Pollock, de Kooning, Kline, Rothko, Guston, and the other pioneers of Abstract Expressionism. His peers were the second-generation followers -- "A host of younger painters like myself who were struggling, fighting, full of energy and argument and drive, demanding, assertive, trying to make an original mark. Looking for the uniqueness of their souls on the canvas."

In New York, Schueler dreamed of making nature the visual basis for his abstraction. He had been fascinated by the sky ever since his childhood in Wisconsin, beside Lake Michigan. In 1957, he found the images he had been imagining, in the Scottish Highlands:

When I speak of nature I'm speaking of the sky... And when I think of the sky, I think of the Scottish sky over Mallaig... Time was there and motion was there--lands forming, colors emerging or giving birth to burning shapes, mountain snows showing emerald green...

Jon Schueler, Red Night Blues, 1987, 72 x 65 inches, oil on canvas (o/c 1514) Private Collection, New York (c) Jon Schueler Estate

Schueler's reflections take us into his studio. They let us hear him unravel some of the visual mysteries of his art, as, for example, in the connection of his time in the air, as a navigator of B-17 bombers during World War II, to the low horizons of his canvases: "Most of my paintings now, paintings of the sea and sky, are painted from an angle of view which I'm sure springs from those flying days."

In 1974 the collector and dealer Ben Heller, who was then representing Schueler, visited him in Mallaig. Schueler reported a conversation the two had as they sat on a hill looking across the Sound of Sleat to the Isle of Skye:

"What people don't realize," [Heller] said, "is that your work is completely abstract."

I nodded.

"And then what they don't realize is that your work is absolutely real."

"That's it, Ben," I said. "That's exactly it. That's exactly what I want. The abstract is real and the real is abstract."

The success of The Sound of Sleat as a self-portrait is a product of Schueler's honesty and of his eloquence. Before he became a painter he had planned to be a writer, and he got a M.A. in English literature at the University of Wisconsin. His critical judgment as a writer stood him in good stead in formulating and pursuing his goals for his book, and in assessing the success and failure of two of his predecessors in writing their own self-portraits:

What I am trying to do in this book is to write about the man who lives, who suffers, who chooses to paint, who wants to have a vision... I think of van Gogh. I think of Clyfford Still. But Clyfford's writing remains self-conscious and posturing. It does not show him at his best, nor does it clarify his meanings. By the very posture he assumes, he obscures the man, and, obscuring the man, obscures the artist. Van Gogh, on the other hand, is so patently naked that his writing has a great force and power.

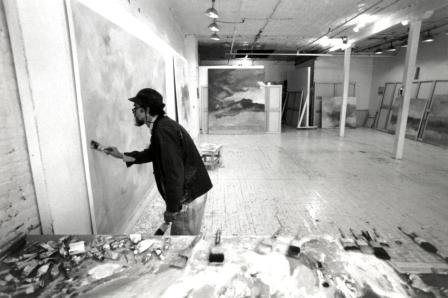

Jon Schueler, 1975-76, photograph by Dudley Gray (c) Jon Schueler Estate (in the 10 Jones Street, New York studio)

When Schueler first arrived in Mallaig in 1957, he wrote to a friend that "there is something here that I have been searching for and that I have been thinking about, and maybe I can find out more about how it works." At the end of The Sound of Sleat, in 1979, Schueler celebrated a triumph with a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum. He was thrilled, but he realized that this was not a conclusion, because for him there was never a conclusion: to him, art was not a product, but a process. His visual, experimental attitude is scorned in today's highly conceptual art world, in which the heirs of Picasso, Duchamp, and Warhol privilege ideas and solutions: most of today's leading artists are finders, not seekers. But the experimental approach has long been a vital element of modern art, from the Impressionists and Cézanne through the Abstract Expressionists. And it continues today, in the magisterial portraits of Lucian Freud, and the entrancing abstractions of Brice Marden.

The Sound of Sleat is one of the most vivid verbal self-portraits we have of the painter as a seeker. It will delight anyone interested in the inner lives of artists who consider their work, and their lives, as a quest to create images as beautiful as those they see in nature.