I first met Enrique Hitchman in a bar with no name on Neptuno Street in the neighborhood known as Central Havana. I had been living in Cuba, off and on, for several years to research the histories of race, national identity, and boxing for my dissertation.

The bartender, Pedro, was an Afro-Cuban in his late sixties. The week before, he had invited me to a funereal ceremony to reinter the bones of one of his brothers in the Abakua brotherhood, an Afro-Cuban secret society whose roots lay in West Africa and the slave trade that had brought the ancestors of so many Cubans to the island.

The day before I met Enrique Hitchman, Pedro had alerted me to be careful in talking to a regular at the bar who worked for state security, and liked to ask probing questions about opinions on Cuban politics. This was a neighborhood where everyone knew everyone else's business and as an American I had become a novelty and conversation piece.

I hadn't been there in a few days, but on this Friday afternoon Enrique Hitchman was asleep on a precarious stool at the bar, his face resting on a large scrapbook that contained the proof of his best days. Pedro and the other bar regulars were very interested in what I was uncovering in the archives, and they had put out the word in the neighborhood for anyone who had first-hand knowledge of boxing in Cuba, the older the better. Enrique had gotten word, and he had come each of the last three days that I hadn't been there, drinking steadily and keeping an eye out for me to come back.

Enrique Hitchman had once been the bantamweight boxing champion of Cuba. When the Revolution succeeded in 1959, he had chosen to stay because he believed in the changes that it entailed and in the ideas that had made idols of Fidel, Che, and Camilo Cienfuegos. Other professional fighters, his colleagues, had chosen to expatriate to Mexico or the United States. The Cuban regime outlawed professional sport in the early sixties because it was seen as decadent and capitalist and had clear connections to the mafia that was a symbol of so many things that the United States had brought to Cuba. Enrique explained his decision to stay in terms of a sacrifice in the name of ideas. Now, his only source of income was as a part time night watchman at a construction supply store, where those who had access to American dollars could buy expensive lumber and other goods to sure-up their aging homes.

Slowly waking, Enrique sized me up and dusted off his four-inch thick scrapbook. His story would come at a price, and he demanded the outlandish sum of thirty dollars, a month's salary for most Cubans. He wanted the money so he could have his wristwatch fixed. The watch was a gift from his father when he won the national title in late fifties. He still wore it, though it hadn't worked in a decade.

Hitchman is an unusual last name in Cuba. Enrique's father had emigrated from Barbados in the late 1920s to work on one of the massive American-owned sugar plantations in Oriente Province. Enrique was what most Cubans would call a mulatto, but he assured me that he was black and proud of being so. He presented his disfigured nose and large, swollen hands as proof of his former livelihood.

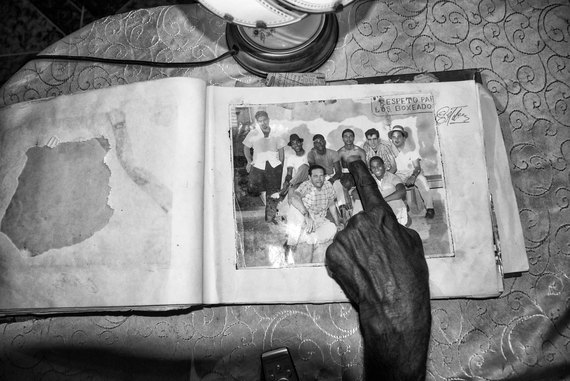

At El Mundo Bar later that evening, the young bartender viewed us with suspicion as we entered and took our seats where the long wooden bar joined the wall. We ordered two beers and with boozy gravitas Enrique opened his book, careful to make sure there was no spilled liquid underneath.

The book contained dozens of brittle newspaper clippings and sepia photographs from the late 1950s and early 1960s. Now balding, Enrique had had a full head of thick hair, all of his teeth, and a boxer's physique that could sell gym memberships. There were pictures of him in the ring, fighting white, black, and Mexican fighters. Other images showed him posing, trying to look threatening, among a group of his fellow boxers after a long training run along the sea front drive. His favorite picture though, was of him in street clothes, smiling behind his young daughter, at a lavish birthday party he had thrown for her with the winnings from a fight in the United States. When asked what happened to her, he evaded the question, muttering that he had a son who lived somewhere in the United States, Chicago, maybe.

As Enrique narrated his memories, young locals gathered around at the bar. The bartender stopped pretending to be upset that no one was buying anything and hung on the old boxer's words and jokes. In many of the pictures, Enrique appeared wearing his champion's belt, he was careful to point it out in each image, looking around proudly and saying "faja!" the belt. One of the last pictures in the book was an eight-by-ten print with Enrique in the center, surrounded by his entourage, with a sign on the wall in the background that read "Respect the Boxers."

For the next few months I saw Enrique often. He had his watch fixed and had bought a new baseball cap, so the women wouldn't see his white hair, he said. We walked through Old Havana and Central Havana, he commented on almost every attractive woman we passed, but they paid him no attention. This was in 2008.

In July of 2014, I returned again to Havana to continue the research I had started on previous trips. The rules of the national library had changed, and now they allowed researchers to photograph the documents, making it much easier than copying every word by hand as had been the previous policy.

I went by the bar where I had met Enrique. No one knew or had heard of what had happened to him. At the building where he had lived no one seemed to know him.

The bar with no name was no longer run by the state. New laws now allowed for limited private ownership and an entrepreneur from the interior of the island was renting the property. He was stockpiling bricks and other materials and had big plans to modernize, even offering imported beers and liquors. He hoped to tap into the tourist trade that was rapidly transforming Old Havana. Pedro, the bartender, had died, he told me.

I made a new friend there, who I'll call Roberto. Roberto had just gotten out of jail. He had been locked up for many years as a political prisoner. He recounted that he had been on a security detail for President Allende in Chile as a young man, but had been in Peru on that terrible day when Allende committed suicide in the face of an American-backed coup that ushered in over a decade of dictatorship, human rights violations, and murder there. He changed the topic of conversation when asked why he had been jailed. He had never heard of Enrique Hitchman.