An issue that has vexed me through much of my political life, and that is different in the United States than in many other countries' political discourse, is what might be called the problem of assumed equivalence. For a variety of historical reasons, the U.S. has two large political parties. Our political debates stem from this political duality; every general election has at most two truly viable candidates, and every issue is framed as having two sides.

During an election year, this tends to mean that every possible campaign issue has no more or less than two positions, and that a fair-minded individual, the self-identifying independent, has the privilege and responsibility of choosing between these positions.

Embedded in this idea are various frequently reasonable, or laudable, assumptions. One is that, if there are two positions, both must have at least some validity. Another is, good people in politics will advance their positions zealously, but within a reasonable, fair set of rules. A third one, that follows from the first two, is that following one position, or leader, without trying another after awhile, is likely to serve people's best interests. It's this last point that we frequently hear from some voters when they say that it's time for a change or that different branches of the U.S. government should have different party leadership.

I myself, a product of a white suburban American lower-middle class background, grew up with these assumptions. My articulate and ethical parents encouraged me to think independently, to judge candidates and their positions on their merits, and to appreciate the idea of two sides to every argument or story, an idea that later resonated in learning to debate and training to be a lawyer.

But what if the assumptions above are wrong? That is, what happens when there an argument doesn't truly have two valid positions, or when one or two parties doesn't play fair or reasonably? If either of these things happens, the third assumption mostly falls apart, and the Independent voter who sincerely believes to be representing political balance may be doing no such thing.

The undermining of the above assumptions, and the destruction of healthy political equivalence, is exactly what I think has happened in the recent presidential election, and perhaps, in U.S. elections more generally. By no means most, but a significant minority of political activists, mostly on the right, espouse positions that are, ultimately, not valid, and push them in an unfair manner that is not about reason. The line of attack that Obama was not born in the U.S. is an example of this. American society is so conditioned on the notion that there are two likely reasonable sides to every story that unreasonable folks can take advantage of this to force issues onto the national stage that are not issues at all.

Note that I'm not saying that activists on the left always resort to fair issues or tactics. But here is exactly where I think we have to be careful about assumed equivalence. It is a particular, but potent , group of largely conservatives, who have built their power base on attack, innuendo, unsubstantiated postures, and repetition who make the rest of us who strive to be fair-minded default to trying to analyze what they say through rationalism and benefits of the doubt that then get exploited.

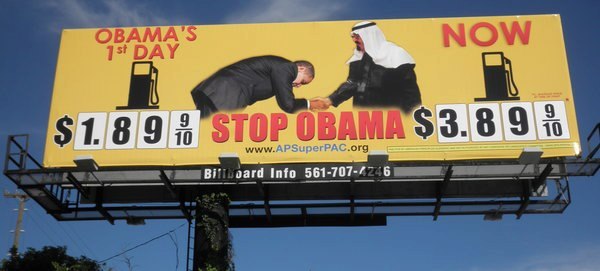

Take the following billboard, which was funded by a conservative Super PAC and highly visible in Florida:

The billboard clearly implies the following propositions:

1) The price of gas went up generally during Obama's presidency.

2) The price of gas in the U.S. is something over which the President has control.

3) If #2 is true, then Obama in fact pursued policies that were entirely insensitive to Americans' desires for lower gas prices.

4) Indeed, something inappropriate about Obama's relations to powerful Arabs (he defers inappropriately to Arab leaders? He is secretly a Muslim?) is the reason that Obama did not pursue lower gas prices.

Personally, I find this billboard extremely offensive. But its problem is that it forces each of the above propositions to be a position that deserves some attention from fair-minded people. Yet only the first of these is something that is subject to clear rational verification, while #2 and #4 are increasingly unprovable, and, indeed, as the numbers increase, increasingly false.

In short, it is truly difficult to embrace the assumption that some issues have two perspectives worthy of consideration when particular individuals and groups seem dedicated to purposefully spreading untenable, nasty positions. Moreover, for the other side, there is a dilemma of how to respond, and a temptation of fighting nasty innuendo with nasty innuendo.

And this is where much of today's American political discourse is firmly lodged. Small wonder that millions of Americans have been expressing fatigue and dismay with the presidential campaign, as it drags on and on in this sort of assumed equivalence that is really mutually assured destructive nastiness.

Given the above, it is actually heartening that the crisis that Hurricane Sandy brought has also brought political figures together who might espouse different positions but come together on common themes. Whatever your reaction to New York Mayor Bloomberg's endorsement of Obama for a second term or New Jersey's Republican Gov. Christie's willingness to stand alongside the President and accept federal money, it represents a modest return to the type of reasoned interaction that flows from an assumption of actual political equivalence. For me, at least, it has given me hope during a long, nasty campaign when my faith in political reason and fairness has been truly shaken, and not equivalently from two sides.