TOKYO, Jan. 26, 1948 -- The third year of the U.S. Occupation of Japan. The Teikoku (Imperial) Bank near Ikebukuro in downtown Tokyo is closing for the day. A man knocks on the door. The man says he is a doctor sent by the U.S. Occupation authorities. The man says there has been an outbreak of dysentery in the neighbourhood. The man says he must inoculate all the employees of the bank. The assistant manager of the bank gathers together the fifteen members of his staff, including the bank's caretaker, his wife and his two children. The doctor pours out the vaccine into their sixteen tea-cups. The sixteen people drink the medicine. Two minutes later, twelve of them are dead, four unconscious and "the doctor" has disappeared along with some, but not all, of the bank's takings.

So begins the largest manhunt in Japanese history. Conspiracy theories abound; theories that suggest the involvement of ex-members of Japan's notorious bacteriological warfare Unit 731; theories of U.S. collusion; theories of a Soviet connection. But eight months later, the police arrest an artist called Sadamichi Hirasawa. Hirasawa initially confesses to the massacre, but then retracts his confession. He is put on trial, found guilty and sentenced to death. However, no Minister of Justice will ever sign the final execution order. And so Sadamichi Hirasawa will live the remainder of his life on Death Row where he dies of natural causes in 1987.

To this day, there is a campaign in Japan to posthumously clear Hirasawa's name and to find the real culprit behind the "Teigin Incident". And this is how I came to the story, though a Japanese newspaper article on Hirasawa and the campaign to exonerate him. And the more I read and the more I researched about the case, the more obsessed I became. And the more confused; there were so many conspiracies, so many theories, and so many tangents surrounding, even obscuring the case. But one thing did become clear; this was a tale of such complexity and uncertainty that it could not be told from one single perspective by one single narrator.

And so I went back to one of the first Japanese stories I had ever read, "In a Bamboo Grove" by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (above) and to the 1950 Kurosawa film of that story, "Rashōmon." In both the film and the original 1921 tale, there are seven different accounts of a rape and a murder. The reader must then decide for themselves which "testimony" is the "truth" (and for readers in 2010 who wish to take up the challenge, I would recommend Jay Rubin's translation in "Rashōmon and Seventeen Other Stories," published by Penguin Classics).  And to me, to use such contradictory and disparate narrative perspectives seemed the only plausible structure for "Occupied City," my own fictional account of the Teikoku Bank Massacre.

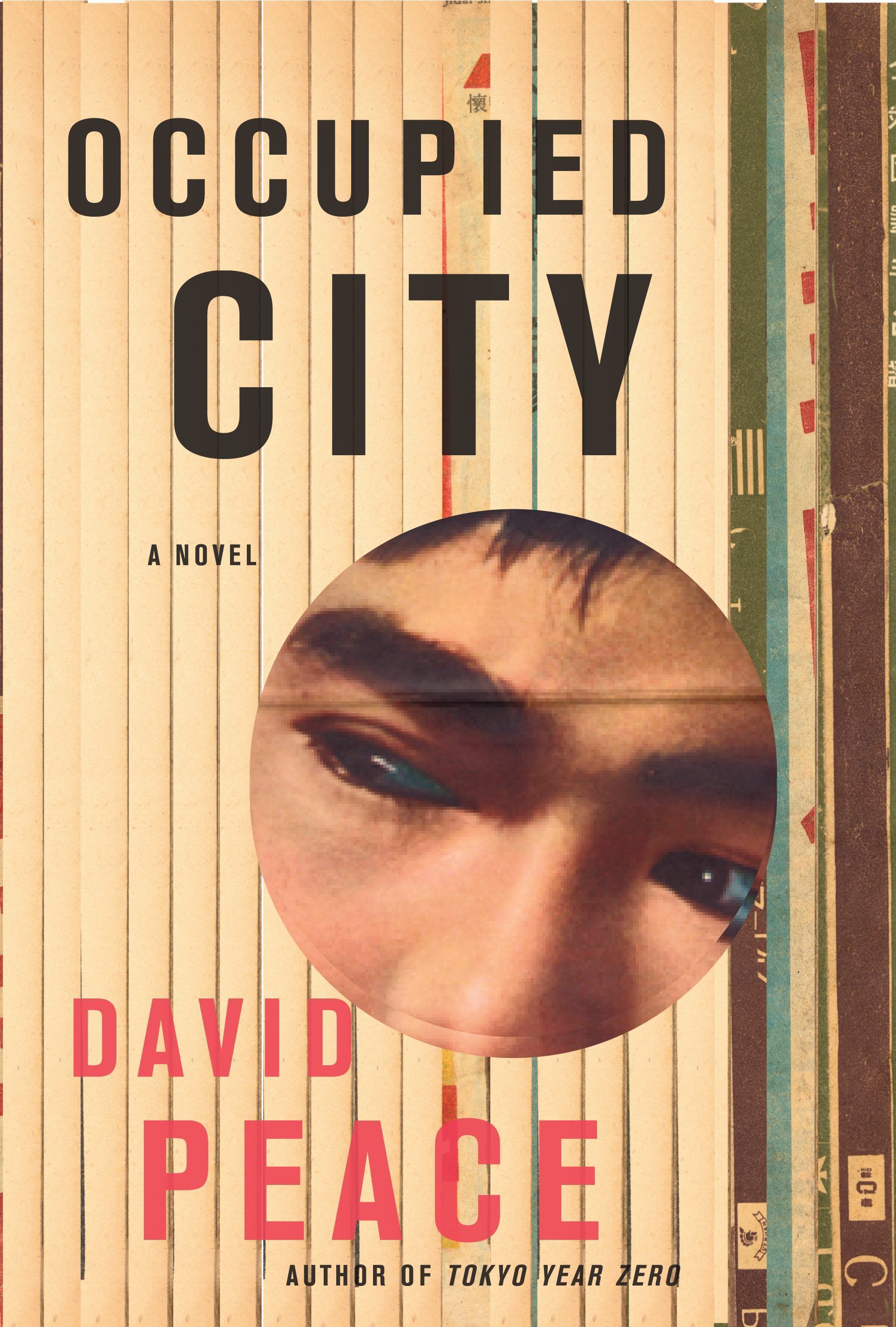

And to me, to use such contradictory and disparate narrative perspectives seemed the only plausible structure for "Occupied City," my own fictional account of the Teikoku Bank Massacre.

In "Occupied City," a writer is visited by twelve "voices"; the twelve murdered victims, two police detectives, a survivor of the massacre, an American scientist, an amateur "occult" detective, a journalist, a gangster-turned-politician, a Soviet investigator, Hirasawa himself, the relatives of the dead, and "the Killer" --

But which voice, which truth will you believe?