Armando Serrano and another man were convicted in the 1993 slaying of a Humboldt Park resident as he left for work. The prosecution's case consisted of testimony by a jailhouse snitch who claimed the men confessed to him, and the widow of the victim who offered a possible motive for the crime. A decade later, the snitch admitted he had lied about the confession, and the widow recanted her testimony. Both swore they had been induced to testify falsely by Det. Reynaldo Guevara, accused of similar misconduct in more than 40 cases. Guevara recently pleaded the Fifth Amendment at an ongoing court hearing that will determine whether the men win new trials. Serrano asked to testify at the hearing, but prosecutors raised procedural objections and a Cook County judge barred him from taking the stand. Who is Armando Serrano -- and what would he tell the world if he had been allowed to talk?

One of 37 Serranos imprisoned in Illinois, officials distinguish Armando from the others by his given name and prison ID: B66082. The Department of Corrections reports that he is behind bars at the Dixon Correctional Center, 106 miles west of Chicago, where he is serving the twentieth year of a 55-year sentence for murder and armed robbery. He is described as a 41-year-old Hispanic, 5'6", 160 lbs., black hair, brown eyes.

Those are the cold facts. Here is Armando Serrano's version of the deeper truths.

"I am a son, a father and a brother. Above all, I am an innocent man sitting in prison," he says in the first of several letters. "I want the world to know, especially the victim's family, that I had nothing to do with the murder of [their loved one.] I am not the killer nor the animal that prosecutors portray me to be," he continues. "I am a human being with a heart that just wants back what was wrongfully taken from me."

Asked about the meaning of freedom as Independence Day approached, Serrano admits he does not really know. "Half of my life I've been imprisoned and the other half I was too ignorant to appreciate it," he writes. "Today, I can say freedom means vindication for my wrongful conviction and to live a normal life. That involves being reunited with my family so we can enjoy the simple things that so many take for granted."

Serrano's family includes his parents, Fernando and Neida, who still live in the two-story brick bungalow on the Northwest Side where they raised Armando, his sister and two brothers. The family is close, gathering for occasional Sunday meals of arroz con gandules (rice with pigeon peas), pollo guisado (chicken stew), pasteles (tamales), with a closing act of zucchini bread and flan.

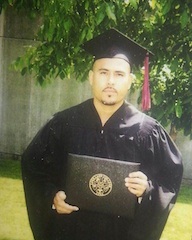

In stark contrast, for 20 consecutive birthdays Serrano and his family have shared slices of soggy cake from the prison's vending machine. Other milestones that would normally have called for all-day fiestas filled with the sounds of laughter and music and children underfoot -- such as the proud day Serrano received his associate's degree in liberal arts (see photo insert) -- are not celebrated at all. Prison regulations prohibit families from taking part.

Undeterred, the Serranos make the trek to Dixon every three or four weeks, often with Armando's sons -- Daniel, 20, and Joel, 19. Now in college, they have no memory of their father outside prison walls. "Life without my sons is extremely difficult," Serrano writes. "I've missed all those moments that every parent holds dear. Their first words, first steps, holidays, birthdays and graduations." But, he adds, "This injustice has not deterred my relationship with my boys. It has instead solidified it."

Other losses have been permanent. Earlier this year, Serrano's grandfather, Inocencio ("Innocence") died at age 91. "We were very close, and he promised he would not pass until after my name was cleared," Serrano wrote at the time. "It pained me not to be able to attend his funeral, but I know he will be watching when I am freed."

Serrano says that freedom became an option not long after he was granted a hearing in 2007 on the new evidence of his innocence -- affidavits by the jailhouse snitch and the widow recanting their testimony. "My lawyer back then told me that prosecutors didn't want a hearing and would agree to time served if I admitted the crime," he writes. By that time, Serrano had been locked up for more than 14 years, but says he did not give the offer a moment's thought. "I said to tell them 'no thanks,' but not in those words. How could I admit to something I didn't do? What kind of role model would I be for my boys? I'd rather die in prison than do that."

When the hearing moved forward last month, Serrano sat in the front of the courtroom wearing prison blues, watching intently as the lead detective in his case took the stand. "It was surreal to see [Det.] Guevara after all these years," he reflects. "I thought I'd be angry, but instead I found myself asking God to help him deal with the damage he caused." As for Guevara pleading the Fifth on every question about the case: "He didn't want to incriminate himself. That says it all," Serrano writes.

Despite two decades of setbacks, Serrano is hopeful about the future. "I currently have an amazing attorney that is fighting valiantly for me," he says, referring to Jennifer Bonjean, a Brooklyn-based civil rights lawyer. Bonjean has taken the case pro bono, even flying back and forth on her own dime for the monthly court appearances.

But Serrano is no longer presumed innocent so "the scales of justice are tilted against me," he acknowledges. "What would help is a transparent examination of all the facts [of] my case. All I've ever asked for is exposure and accountability."

"When the truth is known, it will set me free."

The hearing on Serrano's request for a new trial is scheduled to resume on July 10. To read more about this case, see Police Scandal Eludes Media Radar, Wrongful Conviction Hearing a Revelation, Why Prosecutors Fear Widow's Testimony in Wrongful Conviction Case, A Tale of Two Snitches and Tables Turned at Wrongful Conviction Hearing.