"Dennis Williams, a former death-row inmate whose exoneration became a rallying cry for opponents of the death penalty in Illinois, died on Thursday at his home. He was 46. An autopsy has not yet been performed..." -- The New York Times: March 25, 2003

To outsiders a decade ago this month, Dennis Williams had it all. He was vibrant and gregarious, with a sharp wit and infectious laugh. Women were drawn to him, and his latest "fiancee," Alicia, was as bright as she was beautiful.

And, there was the stuff: a $500,000 spacious home in south suburban Flossmoor and a garage filled with toys, including a Ford Mustang Shelby, a Toyota Land Cruiser and a GMC Yukon. He was often spotted on his Honda Shadow motorcycle, occasionally stopping to chat with neighbors. Living nearby was his best friend since high school, Kenneth Adams, and his wife Norma, both frequent guests at the Williams residence.

It appeared on the surface that life was good for a man who had spent 18 years on death row. Williams, Adams and two other friends -- together known as the Ford Heights Four -- had been wrongfully convicted of an interracial rape and double homicide. On July 2, 1996, they were finally exonerated by DNA and confessions by the actual killers -- local hoodlums whose culpability was known to the authorities almost right from the start. Three years later, the innocent men won a $36 million settlement of their civil rights suit against the Cook County Sheriff's Police, with Williams' share totaling $12 million.

The money had not softened Williams' resolve to campaign against the death penalty and reform the criminal justice system -- "more criminal than just," he quipped. His charisma made him a popular speaker at abolitionist rallies and before legislative bodies. In the six years following Williams' exoneration, he became a leading public figure in the burgeoning innocence movement.

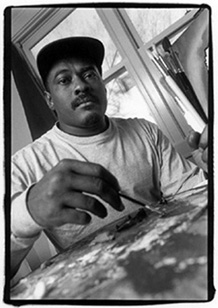

Photo courtesy of Loren Santow

Away from audiences, however, Williams was suffering. His inner world was increasingly dominated by fears and suspicions. He was haunted by flashbacks to life in an 6' by 10' cell near the death chamber and the ghosts of friends lost to the executioner.

A visitor to Williams' home found it dimly lit, partly to conceal cameras he believed would record intruding cops or acts of infidelity. His travels were limited by a fear of flying caused by an obsession that prosecutors would blow up the plane.

As Williams spoke about his unraveling life, he restlessly paced, as if still caged. Chain-smoking menthols, ashtrays rapidly filling, he was never far from a bottle of malt liquor. Drinking calmed him, Williams said, and helped with fitful sleep, a constant issue since his brother died in a garage fire the previous year. Unable to concentrate, he ceased oil painting, a creative outlet that also settled him. Now his only pleasures were talking into the night with best friend Adams and "bolting out" on his Honda bike.

After an embrace, the visitor left, shaken. Adams was similarly concerned, but did not know what to do. His friend refused help.

In 2003, the outside world was surprised to learn that Williams had collapsed at his home, a brain aneurism the likely cause of death. Adams believed it was more complicated than that. His diagnosis: a broken spirit. Eulogizing Williams at his funeral, Adams closed by saying: "The system didn't murder Dennis on death row, but they managed to kill him anyway."

Since Williams' death, at least 695 prisoners have been officially exonerated of major crimes in the U.S. Some died in prison and were posthumously exonerated. Others died free.

But most live on today. How can society help these men and women enjoy a fate different from Williams'?

Lawyers say it starts with money. Unfortunately, it often ends there, too. Williams had enough banked to last him several lifetimes, but it did not prevent the fatal pain of this one. And maybe that was unavoidable, under the circumstances.

But what if the authorities had corrected their mistake before Williams was sentenced to death at age 21? After all, the cops failed to pursue the real perpetrators because of tunnel vision, a common cause of wrongful convictions. And what if prosecutors had agreed to DNA testing when it became available instead of fighting it for years, another prevalent problem?

Want to save lives, prevent lawsuits and restore the integrity of the justice system? Remember Dennis Williams, who lost his 20s, 30s and eventually his life because those in power stubbornly refused to admit their fallibility. Remember the Ford Heights Four, who collectively spent 65 years behind bars for crimes they did not commit. And remember not to lamely claim "the system worked" simply because they were cut loose and paid for their time.

As Williams told reporters on the day his civil rights suit was settled: ''No amount of money can be satisfactory for what has been done to us. If someone asked me 18 years ago, 'Can I buy your life for $100 million or can I borrow your life for $100 million for 18 years?'

"I would have said, 'Hell, no.'''

David Protess co-authored a book with Rob Warden about the "Ford Heights Four case, A Promise of Justice: The Eighteen-Year Fight to Save Four Innocent Men."