Honor Bound In Cuba:

With Values at the Center of our Election Process, Gitmo Remains Open

JOINT TASK FORCE, GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba -

As America struggles through her historic election process, it has also been a year of change for Cuba: this winter, President Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the communist country in 88 years, the Tampa Bay Rays played an exhibition game against the Cuban national team, and the Rolling Stones performed a free concert in Havana before a crowd of over 500,000 people.

With all this going on, throngs of people (Richard Gere, Naomi Campbell, and Jimmy Buffett) were all spotted flying into Havana's José Martí International Airport in March. But not me. As luck would have it, the events conflicted with dates for which I had been granted journalist access to a very different corner of the island.

By now, Guantánamo Bay is so much in the news, we almost take for granted that America maintains a naval base (and military prison) on the territory of a country that has been a declared rival for the past 60 years. That may state the obvious, but on my first trip to the base, flying just 90 miles in over 2 hours to avoid violating Cuban airspace, I was reminded of this epic historical fact.

"It's impossible to observe Guantánamo's recent history in a vacuum from its longer one."

My visit to Gitmo (as the base is commonly called) was a third chapter, a kind of bookend, in a three-part story of my coverage of key events in U.S. foreign policy over the past 15 years. As a photojournalist shooting for Magnum in 2001, I was at work on a photo series about Cuba when the first plane struck Tower One just a few hundred feet away from me in lower Manhattan. I rushed into the apocalyptic chaos on the streets and captured photos of desperation, destruction, and heroism.

A decade later, during the ensuing War on Terror, I traveled as an embed with the 172nd Airborne in Afghanistan to document life for soldiers at the center of a controversial, futile, and misguided conflict, where on the Pakistani border I experienced first-hand the raining of enemy bombs on our troops.

Now, I had the chance to gain a more nuanced understanding of the facility at the center of one of the War's most troubling legacies - first, the decision by George W. Bush to use Guantánamo as a secret military prison, and later, the failure of Barack Obama, despite his campaign promises otherwise, to close it.

Upon arrival at our naval base in Cuba, it quickly becomes evident that the onsite staff is acutely aware of the low regard in which Gitmo is held throughout the world, and why, dating back to the days of torture in Camp X-Ray. Before I even was billeted, I learned a few key things: 1) the U.S. military knows how to secure a facility, 2) detainees are held within Joint Task Force detention facilities on the windward side of the bay apart from the naval base, 3) the current troops know the baggage posited on them by their predecessors, and 4) policy is not set in Cuba, only followed there.

Context is everything, of course, and it's impossible to observe Guantánamo's recent history in a vacuum from its longer one. Established in 1898 after the Spanish-American war and under lease to America by Cuba since 1903 (Cubans today contest the validity of this arrangement), the base has historically handled drug interdiction in the Caribbean, refueling of U.S. Navy ships, and other unglamorous assignments over the years. Above all though, its relevance has been geo-strategically symbolic - an enduring signal of U.S. intentions to maintain sovereignty over the Western Hemisphere.

In 2002, though, the purpose and nature of the base were radically altered when the U.S. government reactivated Joint Task Force (JTF) 160 to guard the facility, created JTF 170 to interrogate those held there, and began renditioning terrorism suspects after 9/11. Soon, the task forces merged to establish "Joint Task Force Guantánamo" to house and secure "enemy combatants" in Camp X-Ray, which was closed after just 4 months following reports of torture. Detainees were next moved to Camp Delta in a remote section of the base for longer term detention in expanded numbers.

Today, 4,000 men and women continue to operate Guantánamo Naval Base. And 15 years after 9/11, another 2,000 JTF personnel are deployed to guard and maintain the detainees in Camps 5, 6, and 7, the newest facilities replacing Camp Delta. With a ratio of more than twenty guards for each of the nearly 80 captives still held there, the annual cost by the military's own estimate, is over $4 million/detainee to detain and secure these possible terrorists.

Naturally, in my mission to revisit the postwar reality of a conflict whose inception and execution I had documented firsthand, I wanted to try to understand the deeper meaning and long-term implications of America's response to 9/11.

And therefore I could not visit Guantánamo without asking to see the detainees, the men that are held indefinitely, and the distinguishing factor that causes such a stir. I am first taken to the abandoned Camp Delta, where the only operational parts now are the medical facilities and the library, which is a labyrinth of shipping containers housing several hundred books in English, French and Arabic.

It's impossible not to imagine the systematic interrogation that was inflicted upon the detainees transferred here from Camp X-Ray. Notwithstanding, I'm here to derive the truest picture of how such a facility continues to function and where its future may lead. Perhaps later, with time to reflect, I can examine the forces - internal and external - that cause a bell-curve of ordinary people like the men and women around me to have done very bad things in these same camps.

So, I went on the approved tour of the facilities, led by capable soldiers doing their jobs. Aside from Delta, I was shown various distractions around the base itself that are meant to keep the troops functional during tours from 9 to 24 months, including the only Irish pub on communist soil (O'Kelly's) and various sports fields, plus an outdoor movie theater with free nightly screenings for the troops (the nearby golf course, "The Lateral Hazard," looked aptly named from the road, as we trundled by). I had meals with captains and conversations with colonels, no one tried to dictate what I would write beyond keeping me on the scripted tour, and I was treated fairly from touchdown to takeoff. Still there's the sense that beyond the daily operation of one of the most secure places in the world, America as a nation is not expressing her best self here.

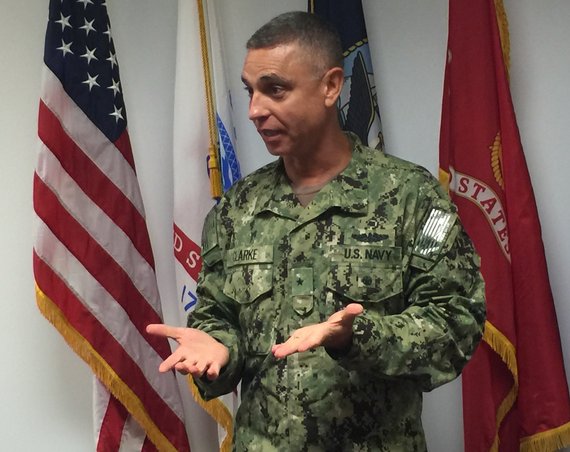

While the Rolling Stones put on an historic rock concert for a half million exhilarated Cubans in Havana, here at the other end of the island, things were unaffected. The goal of Rear Admiral Pete Clarke, commander of all that happens at the JTF, is singular - "the safety of the guard force" - and that mission relies on continuity.

President Obama has made seven years of pledges to close the JTF, yet 76 detainees remain today (32 have been approved for transfer but have not yet been moved). And there is what has been called the "irreducible minimum" with no clear path to determination for those deemed the worst of the bunch. A note for better understanding on what "closing Gitmo" means: this would be the closing of the detention center known as "JTF Guantanamo", but nothing about the naval base would change and those 4,000 civilians and troops would remain.

I was permitted inside Camp 6, where I carefully observed the detainees for some time. It's a strange place by nature - an atrium that's dark and chilly - with a perimeter of cellblocks or "pods" and common areas for tables and food, with two tiers of cells. It resembles a U.S. prison, with the exception of the atrium with the one-way glass.

After standing there in observation, one can't help but think of the endlessness of it all, the lack of any clear path to a determination of their fate as captives, and our standing as captors. It's a nagging and persistent issue that separates this place. Admittedly, it's complicated, as we send here those men we believe have attacked America with the worst intentions. I want the guilty men to be caught, and to pay severely for their bad acts. But, due process counts - and it's what we have sworn to provide even our worst and most hated attackers.

The ability to challenge evidence, hear charges, see witnesses appear and cross-examine them - that's the process part of due process. Here it feels unresolved, because it is. These men were mostly lifted off the streets in faraway places, taken to interim locations, and ultimately dropped into Gitmo for an indefinite period of detention. The process part makes us better, it's not just for them. It's a check on ourselves.

Indefinite detention is a reaction to terrorists and their attacks, not a policy representing the values of a nation. I want terrorists in custody - for our safety, and because we value how we treat others as a measure of our own identity. Give a fair trial, earn the conviction based on facts, don't torture, and stand by the results without a net.

We must all feel accountable to not only have the best troops in the world, but the best policies alongside them.

I was given access to significant personnel at Gitmo. I met with Colonel Heath, who describes his job at JTF as being "just like the warden," and his charge is security at the facilities. The Colonel was straight-forward and well-spoken, and said, "If I was a detainee I'd imagine it would give me some optimism to hear the President intending to close the facility, but I don't know, they don't discuss that with me." He talked about his mandate to keep the facility secure, and stated, "Everything I do here is with one thing in mind, and that is the safety of my guard force." Col. Heath said JTF should close "because the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forced says he wants it closed." Regarding the rule of law, Col. Heath advised that "the consistent application of the rules goes a long way for good behavior... we call what you can control the 'schedule of calls'... when people apply rules inconsistently, it creates a lot of frustration. We avoid doing that if we can."

Later the top commander of Joint Task Force Guantanamo offered his time for questions, Rear Admiral Clarke. We talked about discretion and behavior, and Commander Clarke said "If we ever slip up and we behave contrary to our values and ideals, that's when the detainees win, and we just don't want that to happen." Regarding who comes and goes from Gitmo, that's a matter of policy. I asked Commander Clarke if he does not decide on these issues that are policy in nature, then where does accountability reside? He responded, "Policy in general is set at the office of the Secretary of Defense, or the White House, or if more at the tactical level of how to conduct business here, then at the U.S. Southern Command." And he's right - he with all his considerable authority - earned and deserved after years of exemplary service in the military - he is powerless to decide who comes and goes, or whether they are charged and receive process under the rule of law. His singular mission is to make Gitmo safe and secure, and that he does well.

But has it really all amounted to this? The tragic loss of 9/11, the misguided retaliation in Iraq and around the world from Pakistan to Afghanistan to Morocco, and yes, to Cuba. Has it been worth it? As I observed the men through the one-way glass, I couldn't help but imagine how it may have gone differently.

"We must capture terrorists to protect ourselves; we must also follow the rule of law to nurture self-respect, instead of sowing anti-American animus around the world."

The texture of a place and its people is best understood by standing on the ground, and through personal observation. Last September, after a 15-year hiatus, I visited Havana again on a film project for one of America's pre-eminent documentary film directors. I'm Eugene Jarecki's producer on his recent short film on Cuba called "The Cyclist," part of The New Yorker Presents/Amazon series.

Here is a link, go to Episode 10 to see it:

The film explores the state of U.S.-Cuba relations in these emergent times. The Cuban people are bursting with desire for more access to freedom, while maintaining an enviable love of country that to a person was sincerely expressed regardless of politics or other common gripes against power that all citizens have. So many years later, I appreciate the emerging nature of Cuba, but it begs the question, is America maturing, or in the era of Donald Trump, are we losing ground?

We have honorable men and women serving in the JTF at Gitmo, whom I respect for their commitment to a task that most Americans cannot begin to imagine. I also respect that our country was founded on the rule of law. We must capture and punish terrorists to protect ourselves; we must also have and follow the rule of law to nurture self-respect, instead of sowing anti-American animus around the world.

While the Rolling Stones performed in the name of freedom at one end of the island, detainees lay in endless repose at the other. How can we celebrate the pursuit of liberty there, while we suppress due process here?

Mick and Keith may rule the free (rock star) world, but the citizens of Cuba were forbidden to even listen to Jumpin' Jack Flash after the revolution (the band formed in 1962, just 3 years after Fidel Castro took control). More than 50 years later, the crowd saw an incredible show. Their freedoms, and U.S.-Cuba relations, are evolving. American values should travel with our policies, including to places like Gitmo. There the process rights of the detainees are suspended by semantics, while we try to decide who we want to be.

So, who are we? It cannot have all been for this: the suffering, the dead, the lashing out, the softening morality. All that I witnessed on September 11, 2001, and thereafter, cannot have been for what I witnessed in dark corridors of Camp 6.

We should both secure the detainees under the laws of war, but also provide all of the due process rights as described by our Constitution and the Geneva Convention to which we subscribe. We have the quality men and women in place already - I met a lot of them at Gitmo - but we need our leadership to be accountable to this higher ideal from the top, in order to keep those values alive all the way at the bottom. Our promises must actually become our action: hold our senior elected officials accountable until it happens.

We are wrong on this, and we should feel honor bound to get it right, not only in Havana, but in Gitmo too.

To contact the author, email: davidslucy@gmail.com.

Thanks to:

Rear Admiral CDR Pete Clarke

COL David Heath

CAPT Christopher Scholl

CDR Karin Burzynski

LTC David Olson

LTC Mike Meredith

1st LT. Chris Smith

CTO Frederick Agee

SGT. Patrick DeGeorge

Zak, Cultural Consultant

Navy pilots

Army

Air Force

Marine Corps hey devil dogs

All our armed forces serving in defense of freedom

ROLLING STONES SET LIST 3/25/16 Havana, Cuba:

Jumpin' Jack Flash

It's Only Rock 'N' Roll (But I Like It)

Tumbling Dice

Out Of Control

All Down The Line (Song vote winner)

Angie

Paint It Black

Honky Tonk Women

- Band Introductions -

Midnight Rambler

Miss You

Gimme Shelter

Start Me Up

Sympathy For The Devil

Brown Sugar

ENCORE

You Can't Always Get You Want

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction

Gitmo photo credits: David R. Kuhn

Rolling Stones concert photo credit: Eugene Jarecki