Last Friday morning, a 24-year-old New Jersey woman told me why she joined Occupy Wall Street. Around her, balding activists in their 50s tried to rekindle 1960s-era protests. Young Marxists flew red Che Guevara flags. The young woman, though, was different.

She commuted to the protests, she said, while holding down two part-time jobs. She lived at home and helped her schoolteacher mother, who also worked two jobs, support her jobless, 60-year-old father. She asked to be identified only by her middle name -- Susan -- because she feared her bosses would fire her for attending protests. She didn't talk of revolution. She talked of correction.

"Like any great nation and country, there are also hitches in the plan," she told me. "And things that need to be changed."

Corporate America has gained the upper hand on the American middle class, she told me. A year after graduating from college, she was working as a part-time manager at two different retail chains in New Jersey. The companies use part-time managers, she said, so they don't have to pay benefits.

"It's their policy," she said, "which is why I'm here."

Beneath the online vitriol swirling between supporters and opponents of Occupy Wall Street lies a central question: Does Wall Street help or hurt the American middle class? A variety of forces are slowly gutting the middle class -- and a paucity of values on Wall Street is one of them.

The problem is not every bank. It is a growing slice of the financial sector that has become a vast, computerized casino where staggering fortunes can be won or lost in minutes, with taxpayers left holding the bag.

Members of the middle class, of course, played as well. They bought houses they could not afford, dallied in day-trading and saved too little during an era of limitless credit.

"Finance had become the new American state religion," University of Michigan Prof. Gerald Davis writes in his book Managed by the Markets: How Finance Reshaped America. "All the world was a stock market, and we were all merely day traders, buying and selling various species of "capital" and hoping for the big score."

The middle class, though, is still waiting for its bailout.

As recently as twenty years ago, middle America saw the country's financial system as its ally. For decades after World War II, a carefully regulated Wall Street -- and the American financial industry as a whole -- helped create a growing middle class, according to Yale University political scientist Jacob Hacker. A stable financial industry was a vital part of a vast economic boom, reliably providing home, car and college loans to average Americans, as well as capital to the companies that employed them. Not every banker was malevolent; nor was every corporation evil.

The transformation of Wall Street and America over the last thirty years has been meticulously documented. The traditional, Jimmy Stewart notion of American banks and business, where companies built products, reputations and payrolls over time, has been eclipsed by a byzantine, non-transparent and insider-dominated financial industry.

The middle class -- for me the 60 percent of American household that make $30,000 to $80,000 a year -- have seen their median household incomes shrink in real dollars since the Great Recession ended, while Wall Street salaries have surged. A new study by the New York State Comptroller cited by The New York Times found that the average 2010 financial industry salary was $361,330 -- five and a half times the $66,120 average salary of other New York City private sector workers. Thirty years ago, financial salaries were only twice as high as those of other professionals.

Suspicion of Wall Street is not limited to the dozens of large cities where small protests have emerged. When I visited Bowling Green, Kentucky last week to gauge how the American middle class was faring in one small city, local businessmen lamented the role of the financial industry in the demise of several local companies. Executives used easy credit to rapidly expand firms, companies over-extended over time and eventually collapsed.

The anger in Bowling Green and Lower Manhattan is about excess: excessive risk, excessive ambition, excessive compensation. Companies should make profits, average Americans told me. Skilled executives should be rewarded. And businesses should be viewed as irreplaceable engines of economic growth.

Wall Street, though, should not be an all powerful force that pressures companies to live-and-die by their daily stock value. It should not assign inflated values to fledgling companies. And it should encourage, not deter, companies from developing, innovating and employing over the long-term. Most of all, the financial industry should be held accountable for its performance, like everyone else.

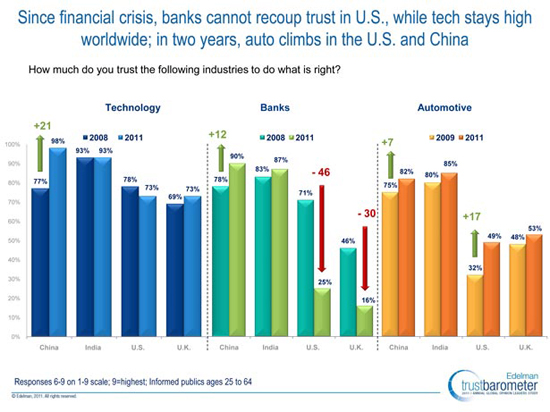

That core moral element -- the sense that Wall Street is making money for nothing -- is the financial industry's gravest threat. Recent surveys conducted by Edelman public relations found that Americans' trust in banks plummeted from 71 percent in 2008 to 25 percent in 2011, a dizzying decline of 46 percent. As this chart from the study shows, the public's trust in the technology industry, meanwhile, remained high.

The response to Wall Street in Washington has been ideological, petulant and tedious. The left has declared all Wall Street suspect. The right has declared the government -- and nothing but the government -- evil. The Volcker rule announced this week is an imperfect, but positive step forward. As much as possible, average Americans should be shielded from high-risk trading.

In another era, middle class Americans might be less incensed by the vagaries of Wall Street. The shift of retirement savings, though, from pensions to 401(k) stock plans has hurled middle America into the markets. During the 1929 stock market crash, only 2.5% of Americans owned stocks. Today, when 401(k)s and other financial products are included, the number stands at roughly 50%.

As a result, an increasingly volatile American financial industry is helping and hurting average Americans to an unprecedented extent. The middle class is more entangled in Wall Street than ever before in U.S. history. And the American middle class is losing.

This post originally appeared at Reuters.