On September 17, 2013, Northeastern University released the results of its second annual Innovation Poll, "Innovation Imperative: Enhancing Higher Education Outcomes."

On page 13 of the 25-page report, we learn that 84 percent of the 263 business leaders who were surveyed agreed that "the ability to think creatively is just as important as the ability to think critically," and that only four percent disagreed. The business elite sample included hiring executives from a cross-section of companies, ranging from small businesses to larger companies with a global presence. Striking that in the 25-page report, the only reference to creativity occurs on that single page.

What we overlook is often as important as what see. Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris illustrated this in their study, "Gorillas in our Midst: Sustained Inattentional Blindness for Dynamic Events," in which participants were asked to watch this video and complete a simple perception exercise (click the link to try it yourself!) Subjects in this experiment literally failed to see the 800-pound gorilla in the room as it entered a basketball game, beat its chest and exited. Why? Because even though it was rather big and obvious, the subjects were not looking for the 800-pound gorilla. There was no illusion or perceptual chicanery. The subjects were instructed to stare directly at the space the gorilla occupied.

The work of Simons and Chabris illustrates a well-known truth: that there is no conscious perception without attention -- i.e. we see what we are looking for. It also illustrates "change blindness," which happens when we fixate on one pattern and fail to see changes in our direct field of vision, even when they impact the pattern.

Take what Kodak didn't see. It didn't see that the year after its largest sale of film that its business would tank. It didn't see that its success and its enormous market share were based on people deciding to go digital and other competitors moving to meet that new market. The 800-pound gorilla.

Selectivity in vision makes it difficult to see a new paradigm emerging, or to meet its demands, without shifting our selective vision. It explains why Kuhn's work notes that scientists working within a paradigm almost always find results that confirm the paradigm by marginalizing anomalies. On the other hand, a scientist in a contiguous field who cannot find what he or she needs will often look into the neighboring discipline and see what the other knowledge workers have missed. Or, of course, you could be like Einstein and sit in the patent office. Regardless, someone not working in that paradigm most often brings about the paradigm shift. Of course, the role of cross-disciplinary collaboration has helped reshape this a bit and promises greater potency in time.

We can also see how glaring disruptions often go unnoticed by more modest knowledge makers.

Here's an example: In a masters of design class that I help teach, teams of students were asked to think about what they would need to know in order to improve their personal and professional performance. The teams had five weeks to research, consider and devise. They were then given 15 minutes to present their results.

One of the teams was incredibly insightful about what they considered to be the "pillars of learning," referring to the concept numerous times during their presentation

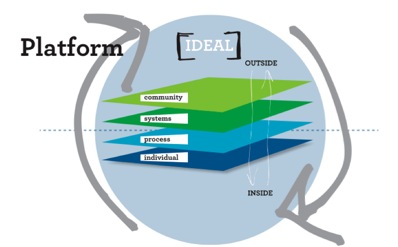

Here's how they illustrated their concept:

They were taken aback when I explained that unless they had been mispronouncing the word "pillows," their illustrations lacked "pillars." What they were calling pillars were neither rigidly and discretely vertical nor static. The graphic shows dynamic, permeable and highly interactive layers, like a soil sample with a great deal of hydraulic conductivity. However, the students were so focused on this concept of "pillars" that they failed to recognize the paradigm shift the graphic was actually illustrating. They were fixated on addressing the original question from an architectural paradigm rather than an ecological one, which was counterproductive because ecology is the new paradigm for system thinkers. Not the building, not the watch, not the car.

Speaking of architecture, we don't even think of buildings as we used to. A decade ago we might have thought of them as sited (presented to the external world, often boldly) and programmed (interiors shaped for the user's needs). Now we don't make distinctions between site and program. The site is also programmed as part of larger overlapping social, cultural, urban and natural systems. It is not discrete or enclosed. The building is open to the world and its force of shaping is not easily defined by internal or external boundaries.

Paradigm shifts, of course, involve whole scale re-thinking, which is difficult. They make us see the implications of our own actions on the world and the way that the conditions of the world enable or disable our actions to be effective.

So how does this affect the idea of talent development?

Recently I spoke with the head of talent development at Groupon, looking for advice. I explained that business leaders in my part of Michigan wanted to move to a talent development model but found that their HR departments were working in a different paradigm and that change was proving difficult. Her response was simple. She told me that it was not an HR problem. She said nothing more, but I immediately grasped her point. It was a systems problem. I was thinking of organizations as machines, but you can't induce talent in a machine. Successful talent development requires that the concept be at the center of the whole organization -- not just in the HR department. Until that happens HR will be powerless to change itself or to advance the organization.

In the same way, any approach to talent development in higher education that is not systemic will fail. It must touch every department and function -- the pedagogical functions with the performance functions with the support functions.

Those who believe in the democratic nature of talent development and its efficacy to move all groups to higher achievement need to understand that their job is not simply to change each student, one at a time, but to change the conditions of creating educational capital every place within and without their institutions.

Next, we will look at some of those "talent" developers and what they are doing. If you are one of them, let me know and I will try to include your work in my next post.

Answer to a question raised in my last post: Why don't we see organized sports as fundamentally creative? Because we see them through the mid-20th-century lenses of factories and the military. The team is a battalion, not a collaborative unit. But that is not the way we need to see it. When organized sports emerged in the mid-1800s, it was seen as a release from the urban, mechanized world and a return to a more primitive, healthful and natural world. So the real answer is that organized sports can be framed anyway we like and its usefulness to society will come from its frame -- the controlling paradigm. And that is the 800-pound gorilla that we are not seeing.