A couple of weeks ago the W. Eugene Smith Foundation announced that Darcy Padilla, a San Francisco-based documentary photographer, was the recipient of its coveted annual grant for "Humanistic Photography."

That term has always puzzled me, because I am hard-pressed to think of any kind of photography that isn't humanistic in one way or another. The grant was established in 1978, the year Smith died, to promote the kind of photography that he made. Actually, I want to say the kind of photography he embodied, because Smith's photographs were lived more than taken. He was famous for his courage and uncompromising spirit: In World War II he was hit by mortar fire while covering the battle for Okinawa. (He is reported to have later said, "I forgot to duck but got a wonderful shot of those that did.") In the 1950s, having resigned from the staff of Life magazine over creative differences, he took on a largely self-financed three-year documentary project on Pittsburgh that left him heavily in debt. In the early 1970s, while documenting mercury pollution in Japan's Minamata Bay, he was beaten by employees of the chemical company responsible for the environmental disaster, leading to the loss of vision in one eye. The humanism in Smith's work came from his willingness -- or need -- to suffer along with the subjects of his pictures.

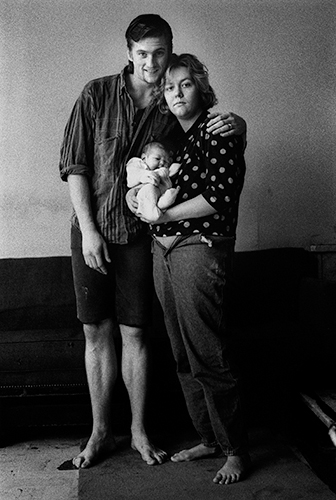

Which brings me back to Darcy Padilla, who won her Smith Grant for a project she started in 1993, when she was 26 years old. While photographing a team of doctors and social workers in San Francisco's Tenderloin district, she met Julie Baird, a 19-year-old recently diagnosed with AIDS. The young woman's pants were unzipped, and she was holding an eight-day-old infant named Rachel. Padilla photographed them, along with the man Baird was living with, who also had AIDS.

The documentary project that grew out of that meeting would last 18 years. Padilla followed Baird from home to home, through health and sickness, through drug use, through the births of three more children, and through an arrest and imprisonment for kidnapping when Baird tried to take two of them from a hospital after they had been claimed by the state. She followed Baird from San Francisco to Stockton, California, and from Stockton to Valdez, Alaska, where she moved in 2005 with a man named Jason to live "off the grid." In 2008 Baird gave birth to her fifth child, Elyssa, and Padilla was there to record the event. And she was there last September 27, when Julie Baird died quietly in her sleep.

Many of the hundreds of pictures Padilla took over all those years are available to view on her website, along with letters, journal entries, and other documents that trace the path of a remarkable journey taken by both photographer and subject.

Last week I spoke with Padilla, and I asked her what I assumed was a logical question: Why? What made her want to spend nearly two decades photographing the unruly and unraveling life of Julie Baird?

She told me that at one point, back when she was studying journalism at San Francisco State University, she thought she might become a photographer for Sports Illustrated, until she photographed a homeless family panhandling for tourists at a cable-car turnaround. "Something just clicked," Padilla said. Later, she interned at the New York Times, which offered a job and a relatively secure future. Instead she became a documentary photographer, like Gene Smith, which meant waitressing jobs and grant applications and freelance work, when available.

She did it, she said, because she was interested in the social issues surrounding poverty and the people she calls "the permanent poor." Explaining their lives became her life's work, in part, I expect, because she understood that no one but documentary photographers and filmmakers seem to do that kind of thing.

And then she met Julie Baird, whose life illustrated everything Padilla wanted to explain about the poor. "Julie was not that unusual," she said.

Except that she was. It does not take 18 years to illustrate a social issue. Nor would a documentary project like Padilla's be so absorbing if that's all it did. When I look at Padilla's pictures, I see a compulsively told story in which drugs, AIDS, and poverty are themes but not the point.

When Padilla speaks, she chooses words carefully, as if she doesn't trust them to explain what she has already said explicitly in her photographs. "I guess what motivated me," she told me after some moments of thought, "was this question that I kept thinking about all those years: How does a child born into this world like every other child, get to be Julie Baird?"

That's a novelist's question. Dickens asked it, perhaps compulsively. Steinbeck. Norris. Sinclair. They all had stories they needed to tell.

"Julie was witty and smart, and she might have grown up to be a teacher," said Padilla. "But her mother was an alcoholic and her stepfather abused her, and she ended up on the streets at age 14."

After 18 years of work, Padilla says she really only captured "a small sliver" of Baird's life. And she now wants to track down all of Baird's children and set up scholarships for them with the $30,000 she received from the Smith Grant. She can't bring an end to the story she began in 1993. Not yet.