We're in deep doo-doo from the global threat of superbugs. The December announcement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) puts that threat back in the news. But I'm underwhelmed by FDA's response, and here's why.

The crème de la crème of public health agree: The infectious threat from super-resistant bacteria -- virtually untouchable with current antibiotics -- is scary. And growing.

In March, Sally Davies, Britain's chief doc, called it a "catastrophic threat" if greater action is not taken. Six month later, she published the book, The Drug's Don't Work: The Global Threat. That same month, the normally staid Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued its own warning: the Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013 report.

Earlier in the year, Drs. Kessler and Kennedy, former Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioners both, had lodged their own strong opinions in print.

The alarm bells are remarkably uniform. They rest on unassailable facts. According to the CDC's report, untreatable or very hard-to-treat infections are sickening over 2 million Americans yearly, conservatively, killing around 23,000 of them. In the future, the number of victims is certain to mount, perhaps drastically.

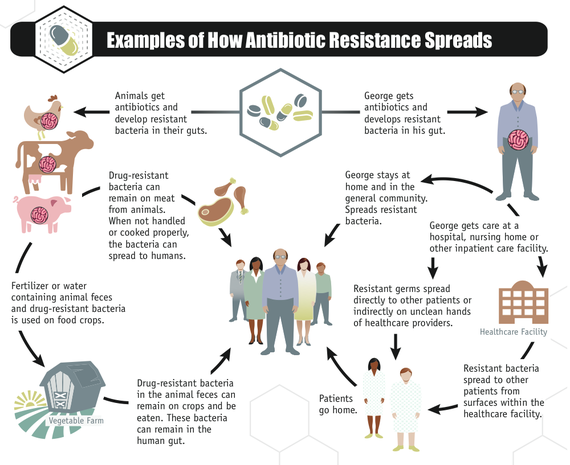

Experts also agree that decades of overusing antibiotics has been critical. It must stop. Overuse in agriculture is important -- no one really disputes that any more. A great new CDC infographic makes it abundantly that it's one big superbug ecosystem out there, with movement of drug resistance from kitchen to hospitals, farms to food, and back again.

Overuse in U.S. livestock is especially important, as the U.S. is one of the world's largest meat producers and exporters. According to FDA's own data, around 80 percent of all U.S. antimicrobials sold are for use in food animals -- the vast majority added at low dosages to feed to promote faster growth or to compensate for the stress of raising animals under crowded and confined conditions. We know this large-scale use has helped create reservoirs of antibiotic resistance in on and around farms, in farm animals, and in the meat supply.

So here's why I'm underwhelmed by the FDA. Beginning in 1999, the European Union phased out the use of antibiotics in animal feed to promote faster growth. In Denmark, this phase-out quickly reduced total antibiotic use by about half. The story in the Netherlands, one of the highest veterinary users of antimicrobials, was more mixed. How a country defines "therapeutic" and "non- therapeutic" use matters. Despite the Dutch phase-out of growth promoters, nothing changed in its food animal production -- at least initially.

From 1999 up to 2006, Dutch use in animals of "therapeutic" antibiotics simply increased to levels that kept the total antibiotic use static. By 2007, 90 percent of Dutch antibiotics were being given en masse to flocks or herds of animals and not to individual sick animals. However in 2010, the Minister of Agriculture set more ambitious goals for actually reducing use, by 50 percent from 2009 to 2013. The 2012 data revealed the Netherlands reached its targets even quicker, with 51 percent reductions in antibiotic use from 2009 to 2012.

While to varying degrees, EU countries seem to be walking the talk on reducing unnecessary uses of human antibiotics in animals, the same cannot be said about the U.S. Thirty five years after the FDA first marshaled the science to show that use of penicillins and tetracyclines in animal feeds was not safe, what the FDA actually announced earlier in December was this: An industry guidance document. That's right. It's a purely voluntary framework for the pharmaceutical industry, if it so chooses, to stop selling their animal antibiotics for the purpose of helping them grow faster.

The replay of the December 11 FDA's teleconference, which I attended (available by calling 866-501-0089), gives the strong impression that the FDA's top priority is to not upset the pharmaceutical industry's apple cart. By that measure, FDA is succeeding. Last month, the Wall Street Journal asked Juan Rámon Alaix, CEO of Zoetis, the world's number one producer of animal drugs and vaccines what he thought of it. Alaix was concise:

[W]e agree with the approach of the FDA to eliminate the growth-promotion indication of certain antibiotics which are relevant for humans in feed. But this will not have a significant impact on our revenues.

By contrast, FDA leadership seems less than focused on public health or the importance to people of having antibiotics that still work. The agency has set no clear targets for reducing antibiotic use in food animals. If the FDA really thinks its actions will reduce agricultural use of antibiotic, then why is Zoetis so content about its future sales?

Along with colleagues at NRDC, CSPI and Keep Antibiotics Working, we have long argued the FDA's approach risks the same bait and switch that occurred a decade ago in the Netherlands. Many human antibiotics currently sold for use in animal feed have multiple uses on their labels, even at the same identical dosage. Lincomycin, for example, is an antibiotic labeled so that poultry producers have FDA approval to feed it to flocks at the exact same dose -- 2 grams per ton of feed - for either growth promotion and for preventing a disease called necrotic enteritis. Voila! Even if the pharmaceutical maker withdraws the growth promotion claim for the product, its customers can continue to use it in the exact same way, so long as they call it "disease prevention."

As part of its announcement this week, the FDA is also asking drug makers to require veterinarian oversight of all antibiotics for use in feed and water. If the drug companies go along with this proposed veterinary feed directive, or VFD, most medically important antibiotics used in food animals will fall under the purview of a veterinarian. (They will no longer be sellable over the internet, for example, without a prescription). But this step, too, is problematic. In order to entice drug companies to make this change, the FDA's proposal (VFD) weakens how much information a vet would have to have before ordering an antibiotic in feed for a farm. Under current rules a vet actually has to be familiar with the farm and the animals in question, before making that order. But under its new rules, the FDA would instead let states decide how much information a vet must have about the farm and animals.

It's the veterinary community generally that has been saying for decades that feeding antibiotics routinely to animals to spur faster growth was a good idea, with little or no human health risk. This, despite that community's promotion of "judicious" use of antibiotics. Finally, the federal Government Accountability Office in 2011 noted the incentive for veterinarians to continue the practice, whatever the guise:

One veterinarian told us that if FDA withdrew an antibiotic's approval for growth promotion, he could continue to give the antibiotic to the animals under his care at higher doses for prevention of a disease commonly found in this species. The veterinarian stated that there is an incentive to do so because using an animal antibiotic can help the producers he serves use less feed, resulting in cost savings.

The FDA's elaboration in its new guidance on what it considers to be judicious use of antibiotics in animal feeds provides little reassurance:

[I]f a veterinarian determines, based on the client's production practices and herd health history, that cattle being transported or otherwise stressed are more likely to develop a certain bacterial infection, preventively treating these cattle with an antimicrobial approved for prevention of that bacterial infection would be considered a judicious use. Another example would be the prevention of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens. In this case, the preventive use of an antimicrobial approved for such use is important to manage this disease in certain flocks in the face of concurrent coccidiosis, a significant parasitic disease in chickens.

Will the FDA's voluntary program work, and quickly enough to help stem the escalating human misery from resistant infections? Only time will tell.

Personally, I was hoping for a little more holiday cheer from FDA. Instead, said Avi Kar of the NRDC, FDA handed "an early holiday gift to industry."