The phrase to "think global and act local" is invoked frequently. But it has taken on a particular new energy across the Pacific as communities address declining fish populations in their traditional fishing grounds. People in small coastal towns remember when the fish was so plentiful they used to swim around the feet of those who got their protein from nature's "icebox" when they needed it. Prohibitions on fishing during certain periods, and restrictions on the kind of fish that could be caught and kept were strictly observed. Punishments were meted out that reflected the gravity of any violation. But as the people whose families have fished in the area for generations know, and as researchers have pointed out, "After western contact, a breakdown of the traditional kapu system and the demise of the watershed as a management unit led to the virtual elimination of traditional Hawaiian fisheries management practices."

Now, concerned grassroots leaders across the islands are saying it is past time to bring back ancestral fishing conservation practices. And the Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) is endorsing the solutions that the community has proposed to the crisis. Last year, the community's rules for the management of the Hāʻena fishery on Kauaʻi were enacted into law.

Restraint to allow the fish to rebound

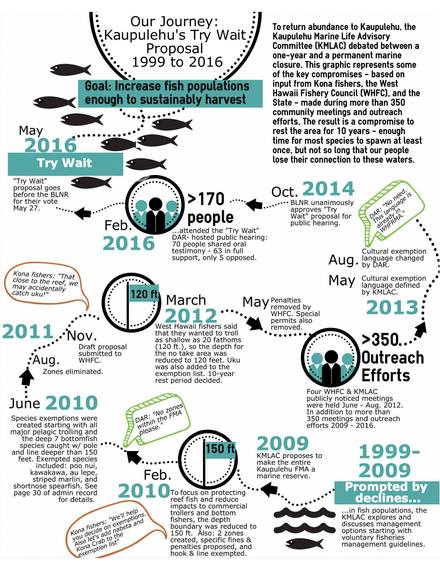

This year another community from the Kona coast on Hawaiʻi island came forward with their proposal. "TRY WAIT" said the T-shirts worn by several members of the Ka'ūpūlehu community, and supporters from the neighbor islands and Oʻahu when they testified before the Board of Land and Natural Resources in late May. The two simple words summed up the community's call for a 10-year moratorium on fishing along a 3.6 mile stretch of the north Kona coast, from Kalaemanō to Kikaua Point, from the shore to a depth of 120 feet (20 fathoms).

The testimony came from young and old, from those who remembered the way it used to be and those who are willing to make sacrifices now for a future in which generations yet to come can enjoy the bounty of the ocean.

Leinaala Lightner's voice broke as she spoke about why the 10 year rest for the reef was important. "I don't want to be the last generation to enjoy feeding my family from the waters," she said, through tears. Her daughter, Malia Lightner's testimony shared on the Ka'ūpūlehu Marine Life Advisory Committee's Facebook page tells a story of shared aspirations:

"We are not trying to take away 10 years of fishing. We fish too. We use the resource too. But we are willing to make a short term sacrifice in order to support our families and generations to come. This is our ahupuaʻa. This is our kuleana. If we don't do something, who will? This is not just for us, or just for me. It's for all of us."

The sense that this is a multi-generational effort was reflected in the mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, grandparents and grandchildren, husbands and wives who joined their energies to advance this effort.

Asked how her son, Kekaulike Prosper Tomich came to be as passionate as she is in advocating for a rest period for the reef, Hannah Kihalani Springer, laughed and said, "Because mama said!" She is proud he has brought his education and professional commitment back to the place where he grew up. She is proud he has embraced the mission of the Ka'ūpūlehu Marine Life Advisory Committee.

A solution from the ground up

The path leading to the realization that the 10 year rest period is needed was lit by input from more than 350 meetings. It was further illuminated by data gathered by the community with researchers working for The Nature Conservancy and the University of Hawaiʻi.

As another Ka'ūpūlehu resident, Shirley Keakealani pointed out, "The 10-year rest period represents a compromise, based on Hawaiian and Western science and Hawaiian cultural values, between the immediate desire for harvest and the long-term need for abundance and sustainability."

Fish righteously

The call to lawaiʻa pono (fish righteously) is a call to conscience. It is steeped in respect for kupuna, a reawakening to the value of ancestral practices that had served previous generations well, and a conviction deeply rooted in Hawaiian culture, that we must look to the past in order to envision the future.

Kelson "Mac" Poepoe of the island of Molokaʻi is widely seen as the godfather of the effort to bring back the fishing practices of his ancestors and mālama 'āina (take care of the land/ocean). As word of his tenacity and the results he has been able to achieve spread, people from across the islands began to come together to share their knowledge through a network started in 2003, known as E Alu Pū ("Move Forward Together")

BLNR's near unanimous acceptance of the community's "Try Wait" proposal was an acknowledgment that to restore the health of the ocean, state agencies must be attentive to the knowledge that resides in the community. In supporting the proposal, Dr. Bruce Anderson, the Administrator of the Division of Aquatic Resources at the Department of Land and Natural Resources, welcomed the fact that the community did not just identify a problem: it studied it thoroughly and came forward with a solution. That solution helps an under-financed and understaffed agency better discharge its obligations to help conserve and ensure the long term viability of the gifts of land and sea that once sustained all the people of these islands.

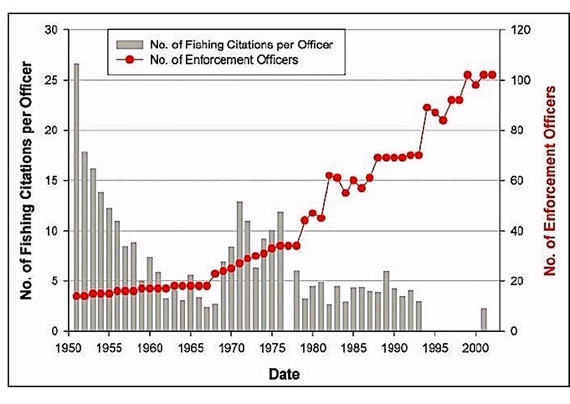

More DOCARE (Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement) officers now, but far fewer citations per officer. (The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Main Hawaiian Islands)

More DOCARE (Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement) officers now, but far fewer citations per officer. (The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Main Hawaiian Islands)

"Try Wait" is one community's commitment to recovering a measure of the food independence Hawaii once had. As Hoku Subiono of the student-produced Hiki Nō series on PBS Hawaii said in a recent episode about ʻōpelu fishing in the village of Miloliʻi: "It's all about taking care of the fish as much as they take care of you."