This is the first article of a four-part series.

"How has the recession affected the Mississippi Delta?" I asked American Blues Scene magazine editor-in-chief Matt Marshall as we tooled down Highway 61 from Memphis airport toward Gateway to the Blues Visitor Center in Tunica MS.

"Ha! It's brought the rest of the country a little closer to where the Delta's always been," he replied.

Tunica was first stop on the book tour American Blues Scene had arranged for my award-winning blues glossary The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu during Bridging the Blues, a 12-day event connecting Highway 61 Blues Festival and King Biscuit Blues Festival. As I traveled through the region, I discovered that passionate blues fans and entrepreneurs, as well as state and local governments, are committing significant time and money to see if blues tourism can make an economic rescue of this culturally significant region -- the poorest in our nation.

So if you haven't paid a visit to the Mississippi Delta yet, plan one now to this starkly beautiful, richly musical place. You'll thank me as you roll down 61, with cotton fields fanning out on either side under an impossibly wide blue sky, following the Mississippi Blues Trail to Robert Johnson's gravesite or to Dockery Farms -- where the first Delta blues stars, Son House and Charlie Patton, worked and lived.

These semi-mythic locations used to be tough for outsiders to find, but since the first Mississippi Blues Trail marker was unveiled six years ago, they've been emerging from the mists of time one by one.

Down in the Delta, the food is heavenly (if you dig real mayonnaise and your vegetables fried), the people are friendly and the music is nonstop and authentic. Cotton is still king, but it's no longer picked by hand. Farming has been mechanized, and workers struggle to find employment and the dignity of self-sufficiency. This cradle of American rock, jazz and blues needs us to come spread some love and tourist dollars around.

Nearly every blues legend I interviewed for my book -- like Robert Jr. Lockwood, Hubert Sumlin and "Little Milton" Campbell -- grew up here, as did B.B. King, Muddy Waters and more. This birthplace of the blues is a two-hundred-mile, leaf-shaped plain that flooded each spring before man intervened, and holds some of the world's most fertile soil. The land is completely flat from Memphis to Vicksburg, bound by the Tallahatchie and Yazoo Rivers to the east, and the Mississippi River to the west.

Today, the Delta is covered with cotton and soybean fields, and dotted with little towns -- but that river-rich soil was once hidden under dense forests and canebrakes. Cotton farmers began the hard, slow work of clearing the land in 1835, with little progress. Determined to get back on their feet after the Civil War ended in 1865, farmers redoubled their efforts to clear the land and build levees to block the flood waters. Thousands of freed slaves migrated to the Delta, recruited by labor agents promising higher wages and civil rights.

Irish immigrants flocked to the Delta, too. Like black workers, many were forcibly conscripted to work on levee and land-clearing crews. Irish workers were called "white niggers," and local storefront signs often read "No Blacks, No Irish."

Building the levees was dirty, dangerous work. Mules and men were killed or injured tumbling down the steep, muddy slopes. Lonnie Johnson's "Broken Levee Blues" tells the story:

The want me to work on the levee/They're coming to take me down

I'm scared the levee may break and I might drown

The police run me out from Cairo, all through Arkansas

And they threw me in jail, behind these cold iron bars

They said, "Work, fight or go to jail." I said, "I ain't totin' no sacks."

I won't drown on that levee and you ain't gonna break my back

This intense push created a new economy -- and a new society among poor blacks and whites. As polished blues bandleader "Little" Milton Campbell Jr. told me: "Prejudice? Yes, there was in some areas but for years and years you had whites and blacks living next door to each other in the same neighborhood, getting along. They would visit, they would be together, and of course," he added, laughing, "some of them would sleep together, which you can understand when you see the different shades of skin!"

This intense push created a new economy -- and a new society among poor blacks and whites. As polished blues bandleader "Little" Milton Campbell Jr. told me: "Prejudice? Yes, there was in some areas but for years and years you had whites and blacks living next door to each other in the same neighborhood, getting along. They would visit, they would be together, and of course," he added, laughing, "some of them would sleep together, which you can understand when you see the different shades of skin!"

Campbell was born in 1934 to sharecropper parents in Inverness, MS. Sharecropping is a feudal economic system that emerged after the Civil War. Many plantation owners couldn't afford to buy seeds and fertilizer, let alone pay workers. Meanwhile, their freed slaves had no work and nowhere to go. Many were still living in slave quarters or shacks they'd thrown up, trying to grow enough food in their gardens to survive.

A bargain was struck. Landowners mortgaged their properties for bank loans to buy seeds, plantings, tools and provisions for their freed slaves. Ex-slaves, in turn, agreed to plant, tend and harvest crops in exchange for shares of the money the crops would bring when the landowner sold them.

Because the landowners sold the sharecroppers supplies on credit, though, the owners could set prices and interest rates as they wished. Although some landlords were fair, many overcharged so that a sharecropper's harvest earnings after expenses might total zero, or even leave the cropper in debt.

Still, a picker in the hill country could earn about a quarter a day, but in the Delta he could make a dollar or more. Fall cotton pickers often went home, packed up their families, and moved to the Delta to sharecrop year-round. Large plantations like 10,000 acre Dockery Farms hosted as many as 250 families. Owner Will Dockery earned a reputation for treating his croppers fairly that attracted more workers. Today, the family runs Dockery Farms Foundation, chaired by blues and Southern culture scholar William Ferris.

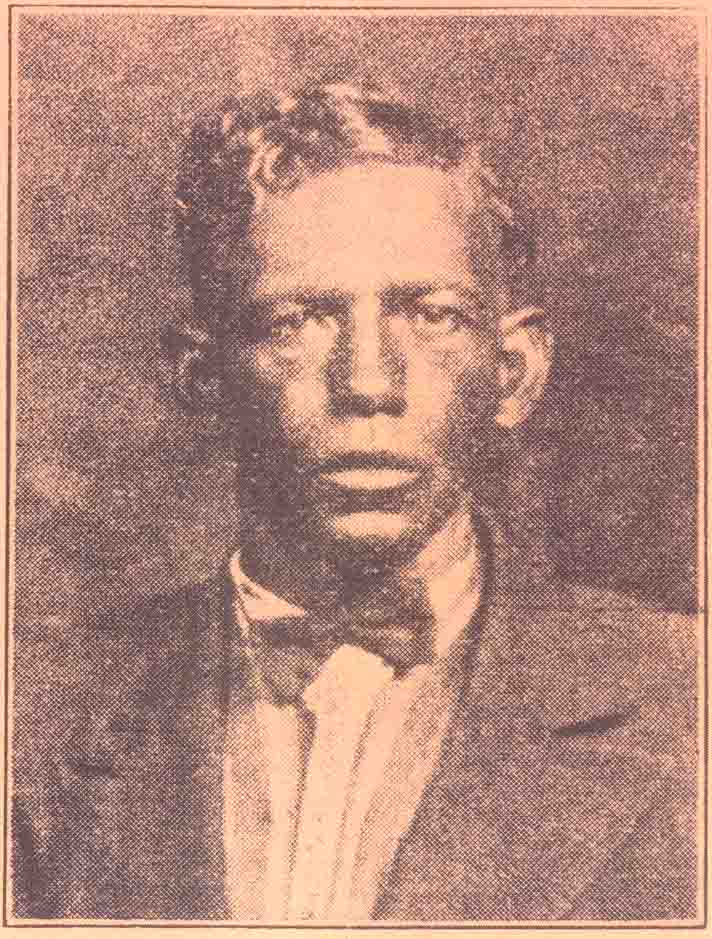

Dockery was home off and on to Charlie Patton, an enormous influence on Howlin' Wolf and the teenage Robert Johnson, who hung out at Dockery. Patton and his friends Willie Brown and Tommy Johnson played parties, picnics, and fish fries in the tenant quarters. Wolf moved to Dockery in 1929 not only to work, but also to learn from Patton.

Dockery was home off and on to Charlie Patton, an enormous influence on Howlin' Wolf and the teenage Robert Johnson, who hung out at Dockery. Patton and his friends Willie Brown and Tommy Johnson played parties, picnics, and fish fries in the tenant quarters. Wolf moved to Dockery in 1929 not only to work, but also to learn from Patton.

More next week! To find out what the words in your favorite blues songs really mean, check out my book The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu and my weekly American Blues Scene magazine column, "The Language of the Blues

Photo credit: Paramount Records catalog; courtesy photo archives, Delta Haze Corporation.