Some of the most idyllic and memorable times of my early youth are the days and weeks I spent in the late 1940s with my parents and sister in the Oriente of my native Ecuador.

The Oriente is Ecuador's magnificent jungle region on the East side of the majestic Andes Mountains. It is the beginning of the Amazon rain forest basin -- some parts still pristine -- and one of the most biologically diverse regions on earth, an ecological miracle.

My sister and I visited our parents in the Oriente during our school vacations. My sister would chase the colorful, gigantic butterflies and admire the delicate, iridescent colibris, not realizing at the time that Ecuador has thousands of species of butterflies and is home to one of the largest profusions of hummingbirds in the world.

I would spend my days playing Tarzan, climbing some of the trees that reached for the sky, not knowing that the rainforest has 2,200 varieties of trees or that they are a critical part of our planet's "lungs." Of course, we knew that we had to be careful of poisonous snakes, frogs and certain plants. But we did not know then that such toxins and some chemicals from a treasure trove of "medicinal plants" would be used to make potent new medicines, powerful painkillers and -- who knows -- one day the wonder drugs that will cure cancer and other cruel diseases.

Our parents lived in a "company compound," Shell Mera, on the banks of a river at the headwaters of the powerful Pastaza, which eventually disgorges into the mighty Amazon.

At the end of our delightful, adventure-packed days, my sister and I would listen to our father tell us about his latest encounter with some heretofore unknown animal or insect, or how one of the company planes had flown low over the huts of some indigenous tribe, visible through openings in the emerald canopy, and dropped beads and small mirrors trying to establish contact with the natives, only to see them raise their bows and arrows or point their spears and blowpipes at the airplane.

For my sister and me, our short visits to the Oriente were like trips to Paradise.

But soon there would be trouble in Paradise, and it would be spelled O-I-L.

You see, underneath the lush Ecuadorean rain forest lie some of the country's largest oil deposits, Ecuador's principal export and one of its most important sources of revenue -- a resource that has been both a blessing and a curse.

While still visiting Paradise in the late 1940s, the oil company our father worked for, Shell, discovered the heavy, viscous oil below Ecuador's rain forest but apparently decided that the extraction, transport and other logistics were not economically or technically feasible. After a few more years, the company pulled up stakes but, to its credit, left the rain forest of Ecuador pretty much as it had found it.

Others, however, would not be as kind to El Oriente.

In a damning New York Times opinion piece a year ago, Bob Herbert describes the new arrivals this way:

Texaco came barreling into this delicate ancient landscape in the early 1960s with all the subtlety and grace of an invading army. And when it left in 1992, it left behind, according to the lawsuit, widespread toxic contamination that devastated the livelihoods and traditions of the local people, and took a severe toll on their physical well-being.

The lawsuit mentioned by Herbert was filed 18 years ago on behalf of 30,000 rainforest inhabitants against Chevron, which had merged with Texaco.

A brief filed by the plaintiffs says:

[The company] deliberately dumped many billions of gallons of waste byproduct from oil drilling directly into the rivers and streams of the rainforest covering an area the size of Rhode Island. It gouged more than 900 unlined waste pits out of the jungle floor -- pits which to this day leach toxic waste into soils and groundwater. It burned hundreds of millions of cubic feet of gas and waste oil into the atmosphere, poisoning the air and creating 'black rain' which inundated the area during tropical thunderstorms

.

The unprecedented multi-billion dollar lawsuit will eventually be settled, in one way or another. However, the incalculable damage done to Ecuador's Oriente will be with us -- with the Ecuadorean people -- for generations to come.

Deeper in Ecuador's Amazon rain forest, at the border with Peru, lies an even more pristine region, the Yasuní National Park. The Park is a nearly 4,000-square-mile rainforest wilderness of incredible biodiversity and the ancestral land to two of the most isolated and "uncontacted" indigenous tribes, the Taromenane and Tagaeri.

The region is so precious, so unique, that in 1989, Yasuní was designated a UNESCO "Man and the Biosphere Reserve."

According to a 2010 research article in the Journal PLoS One, this "quadruple richness center" encompassing less than 0.5% of the Amazon Basin, has 150 amphibian species, "a world record," and 121 species of reptiles. An average upland hectare in Yasuní contains 655 species of trees (more than the United States and Canada combined) and 100,000 species of insects. One section of the park holds at least 200 species of mammals, 247 amphibian and reptile species, and 550 species of birds, making the park the most biodiverse and the richest biological incubator on earth.

Yasuní is also home to a considerable number of endemic and endangered species, including several species of mammals and rare birds.

Sadly, because the Park sits atop an estimated 850 million to 1.3 billion barrels of oil reserves -- Ecuador's second largest untapped oil reserves -- this fragile and irreplaceable habitat has become the next target for oil companies. Companies that each year wipe out approximately 600 square miles of Amazon rain forest for the sake of oil production

But, finally, some sanity appears to be surfacing.

In a recent article in the Huffington Post, Johann Hari puts it this way:

Sometimes, there are hinge-points in human history -- moments when we have to choose between an exuberant descent into lunacy, and a still, sober voice offering us a sane way out. Usually, we can only see them when we look back from a distance.

What Hari is referring to is Ecuador's unprecedented and innovative plan -- some call it crazy, unworkable, even "heresy" and blackmail -- to leave the oil in the ground at Yasuní (estimated to be worth $7.2 billion) if the international community pledges to pay for half of the oil's value, $3.6 billion. The money is to be used for the country's sustainable social and economic development, for renewable energy, conservation and reforestation projects.

Not exploiting the oilfields in Yasuní will also benefit the global environment. For example, it would prevent the emission of approximately 410 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (equivalent to the annual emissions of France) which would result from burning the Yasuní fossil fuels.

Ecuador's President Rafael Correa first presented this historic initiative to the world community in 2007.

Getting pledges for the Yasuní Ishpingo Tambococha Tiputini (ITT) Initiative (named after the three oil fields at Yasuní) has not been easy. A few countries have offered small amounts towards the Initiative's fund. An initiative that has received mixed reviews, in Ecuador and elsewhere.

According to recent reports, Mr. Correa's offer to leave the oil untapped is conditional on receiving the funds requested -- and unless the first $100 million arrives by the end of this year, he would begin extracting oil from Yasuní.

Environmentalists and ecologists are keeping their fingers crossed. If this plan fails, it could mean even more destruction of Ecuador's irreplaceable rain forest with dire consequences for Ecuador and for our planet.

I will be returning to the banks of the Pastaza in a few days -- the first time in 60 years -- anxious to recapture some of my dreams in Paradise, prepared for disappointment, but with hope for the future.

===

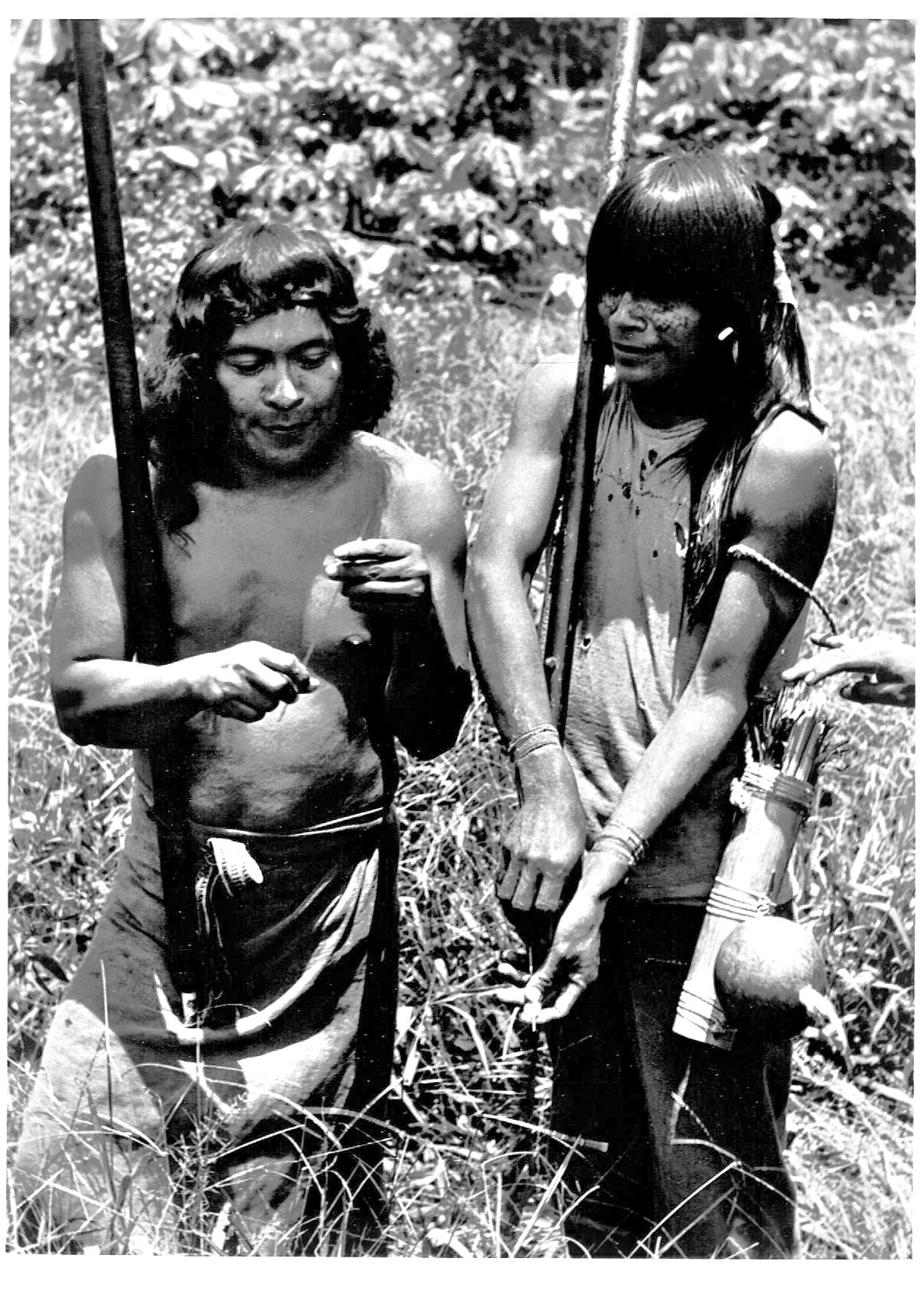

Photo by our late Father who wrote on the back of it: "Chief Taisha, of the Jivaro head hunters and his son, Segundo, with their 16-foot blowpipes, September 1948."