I should have realized it was the spirit of World War II hero Ira Hayes that was whispering to me every time I drove by his home near Phoenix, Arizona. I've spent much of the winter out here and have driven back and forth between Phoenix and Green Valley several times, traversing the Gila River Reservation where Hayes was born and raised.

And where he died in 1954 at the ripe old age of 32.

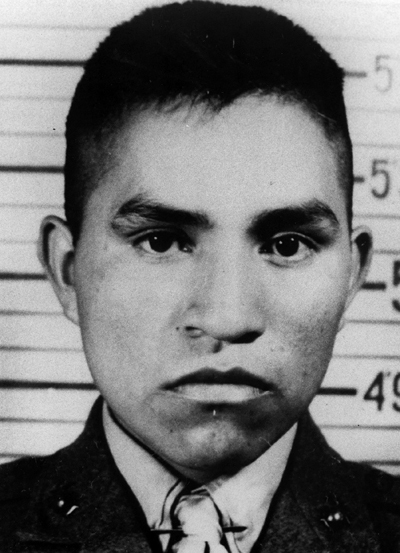

On February 19, 1945, Hayes (nicknamed Chief Falling Cloud because he was Indian and a paratrooper) and a few hundred of his fellow Marines landed on the tiny island of Iwo Jima. Four days later, he and five others raised the American flag over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima, an activity captured by Joe Rosenthal of the AP in one of the most iconic photographs ever shot. It became the only photograph to win the Pulitzer Prize for Photography in the same year as its publication and came to be regarded as one of the most significant and recognizable images of the war -- and possibly the most reproduced photograph of all time.

Regrettably, only Hayes and two others in that famous photo got out of World War II alive, and their lives, especially Ira's, were never ever the same after that famous moment.

But the voice that whispers to me from the Gila River Indian reservation doesn't speak of glory or honor or war or heroism. Nor does it speak of the years of injustice Hayes and his fellow Indians were subjected to. The voice, Ira Hayes's voice, tells of survivor guilt and PTSD and the long road home from war and killing. And it reminds me that some of us former soldiers, like Ira Hayes, never do make it back, even after we physically return to our homes and communities.

Unlike other vets plagued by similar tribulations, Ira Hayes had to deal with his demons out in the open where everyone could see. He became an instant celebrity and was everywhere and anywhere the U. S. government wanted him to be -- fundraisers, flag wavers, war bond sales, dedications, even Hollywood movies. The reality was that he hated every minute in the spotlight. In 1954, just before he died, Hayes was feted at the dedication ceremony of the Marine Corps War Memorial where he was lauded by President Dwight Eisenhower as a "national hero." Later, a reporter approached Hayes and asked him, "How do you like the pomp and circumstance?" Hayes hung his head and said, "I don't."

In order to cope with the limelight and the guilt and his PTSD, Ira Hayes turned to alcohol. He was arrested 52 times for public drunkenness, admitting after one such arrest that "I was sick. I guess I was about to crack up thinking about all my good buddies. They were better men than me and they're not coming back. Much less back to the White House like me." According to the Pinal County coroner alcohol contributed to the death of Ira Hayes in early 1955, at the age of 32. There are no iconic photographs to capture his sad, untimely death.

But there is a song, one that was written by Peter La Farge and made popular by the likes of Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan. My favorite is the version by Johnny Cash, both because of the ferocity and anger Cash brings to the lyrics

Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won't answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinkin' Indian

Nor the Marine that went to war

And because of a story Cash tells in his autobiography, Ring of Fire, about a night in 1968 when he sang that song to thousands of U. S. soldiers in Vietnam on the very base where I would be stationed a few years later. "One night at Long Binh," writes Cash, "a Pima Indian boy--crying, and with a beer in his hand--came up to the stage while I was singing 'The Ballad of Ira Hayes,' which is about the Pima Indian Marine who helped raise our flag at Iwo Jima. At the end of the song, that young Indian asked me to take a drink of his beer, and with the tears running off his chin, he said, 'I may die tomorrow, but I want you to know that I ain't never been so alive as I am tonight.'

Native Americans like that young Marine and Ira Hayes and others have fought valiantly in all of America's wars. Vietnam was no exception. Who knows if the Pima Marine who spoke with Johnny Cash that night in Vietnam ever made it home? Or if he came back haunted by the same demons that tormented Ira Hayes? We do know that Ira Hayes was buried in Section 34, Grave 479A at Arlington National Cemetery on February 2 1955.

But for me Ira Hayes is still somewhere on that Gila River Reservation. Or maybe atop Hayes Peak, the northernmost mountain in the Sierra Estrella range near Phoenix. Arizona, that's been named after him. Or repeating the verses in Peter La Farge's ballad.

He died drunk early one mornin'

Alone in the land he fought to save

Two inches of water in a lonely ditch

Was a grave for Ira Hayes

"The way I feel about it," lamented Johnny Cash, "is the only good thing that ever came from a war is a song and that's a hell of a way to have to get your songs."

On that Ira Hayes would agree.