[Photo credit: Alexis Rife]

Throughout history, people living near any sea coast have relied on fish as a key dietary staple. Middens of kitchen and household wastes left behind on all continents provide strong evidence of the long and deep linkages between people of the shores and the sea. Now, new science published in the top-tier journal, Nature, makes abundantly clear that fish continues to serve an even more important role in human nutrition than experts have previously appreciated.

Every ocean conservationist knows by heart a key statistic: three billion people around the world depend on fish as a key source of protein. That number (varying from three to even five billion, depending on how much protein is "key") comes from the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), from "food balance sheets" that track the production and movement of every major food source in the context of changing populations. This tool is used to determine the percentages of total protein and animal protein that come from various sources, for countries around the world.

Food balance sheets from the just-published 2014 Yearbook of Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics, based on 2013 data, show that many nations remain highly dependent on fish for animal protein, with major fishing nations in food-insecure regions near the top of the list, including Bangladesh (56 percent), Indonesia (55 percent) and Myanmar (47 percent). Some countries in West Africa, and many island states, approach or even exceed 60 percent of animal protein from fish.

Now, a new study by Christopher Golden and colleagues calls the protein insufficiency risk, "the tip of the iceberg." They went one important step further, to factor in deficiencies of specific nutrients that are directly related to important human health outcomes, including micronutrients like zinc, calcium and iron, vitamins A and B12 and DHA omega-3 fatty acids. They created a huge new database (Global Expanded Nutrient Supply, GENuS) that combines the FAO food balance sheets with production and trade data, as well as food group intake by age and sex, to estimate edible supplies and consumption patterns for 225 foods, and then to estimate nutritional availability and vulnerability.

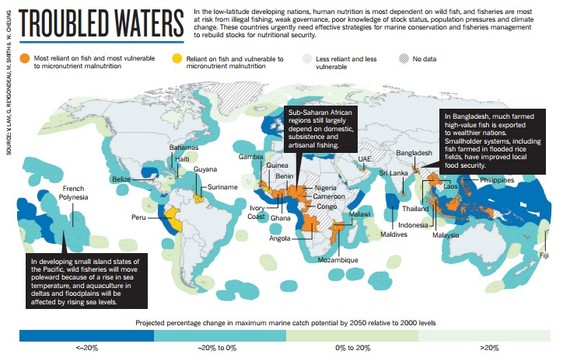

The researchers noted that 17 percent of the world population is already zinc deficient, that 20 percent of pregnant women already suffer iron-deficiency anemia, and that one third are already vitamin A deficient. Their new estimate is that today 845 million people (11 percent of the world population) are "poised to become deficient in one of these three micronutrients if current trajectories in fish-catch declines continue" and that 1.39 billion people (19 percent) are vulnerable to deficiencies and health impacts attributable to their dependence on fish as a limiting source of those key nutrients. They highlight special risks in South and Southeast Asia and West Africa.

Golden and company argue that the current trend of declining fish catches, documented in the Sea Around Us project, is likely to be exacerbated in many places by climate impacts, and will expand these risks significantly in the future, as the world population grows to nearly 10 billion by 2050, and past 11 billion by 2100. Undernourishment is already responsible for 45 percent of childhood mortality and for 50 percent of years lived with disabilities for children age four and under. The new model predicts that fully 10 percent of the global population will face micronutrient and fatty-acid deficiencies over coming decades, with the resulting health effects concentrated in the developing nations near the Equator, if nothing is done to fix overly intensive fishing.

The authors see some hope in expanding fish farming, as long as that is uncoupled from the wild-fish feeds currently in heavy use on fish farms.

I -- and our academic colleagues -- argue that there is also huge opportunity to transform wild fisheries, both to elevate fish stocks and improve ocean ecosystem health, to provide much more fish as food, and to provide income to help pay for nutrient-rich foodstuffs of all kinds, especially in vulnerable parts of the world.

Our recent paper in PNAS shows that 16 MMT per year of sustainable wild-caught fish can be landed from the world's ocean waters, feeding at least a half billion more people their annual protein. This new work suggests that, with careful management, this additional supply of fish would also supply an even more critical additional supply of micronutrients that could help keep those extra billions of people healthy!