A 2005 survey of 401 chief financial officers revealed that CFOs of publicly traded firms are routinely willing to sacrifice shareholder value to meet earnings per share (EPS) targets and smooth reported earnings. This includes passing on valuable new projects and scrimping on R&D. According to the study, CFOs of private firms are equally willing to sacrifice long-term value to preserve credit worthiness and to establish a stable track record of earnings for possible future IPOs. The study's authors coined the phrase "excessive short-termism" to describe this willingness to sacrifice long-term value creation in order to hit short-term financial targets.

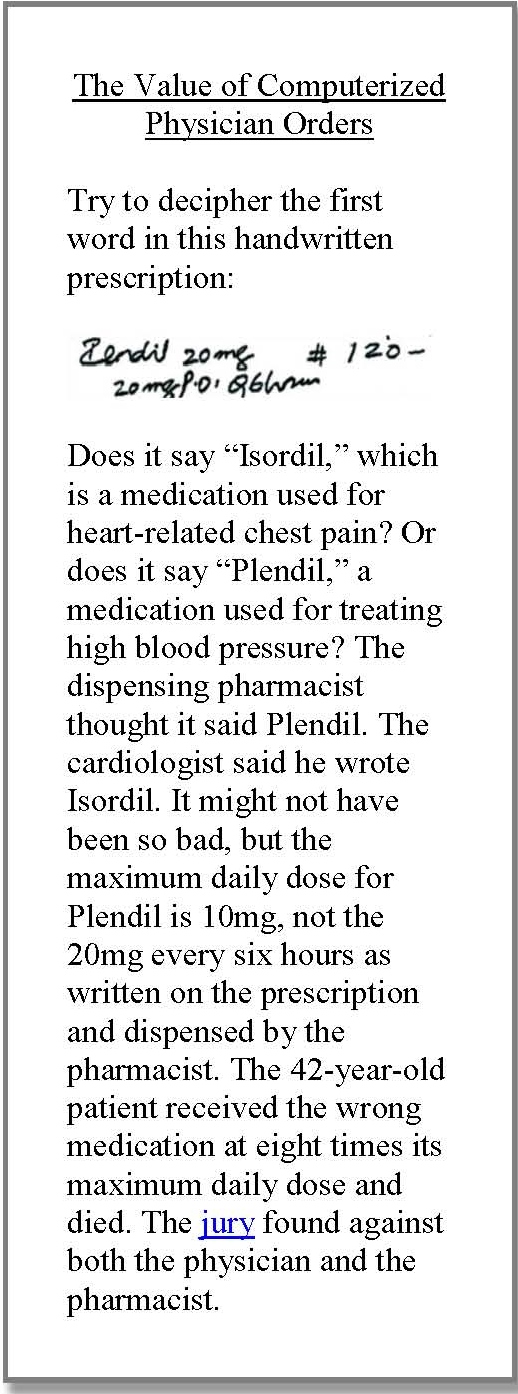

Unfortunately, excessive short-termism is not limited to public and private firms. It has also become an uncomfortable characteristic of many non-profit and for-profit hospitals. Similar to other businesses, the motivation for hospital excessive short-termism is to meet annual operating margin targets and preserve bond ratings, but the value forgone affects society, not just shareholders, and has slowed and even distorted the evolution of hospitals themselves. For example, until President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which instituted financial penalties for slow adoption of electronic records, 90 percent of hospitals still did not have a "basic" electronic medical record system, defined as a record that includes electronic physician and nurse documentation. Hospitals' reluctance to invest adequately in electronic medical records continued for two decades despite a 1991 Institute of Medicine report that called for the widespread adoption of electronic records over the following 10 years, and the unarguable evidence that poor physician handwriting and paper records lead to errors.

Many other examples exist of bright innovations in patient care, safety, and service that have been defeated by the query: "What's the ROI?" or the reminder: "We are not reimbursed for that," which is why hospitals still struggle with decades-old, solvable problems, such as how to ensure that most employees wash their hands frequently, how to prevent falls, and how to eliminate the occurrence of surgeons mistakenly leaving surgical sponges or instruments inside patients. It's also why hospital customer service lags behind consumer expectations--how many hotels still have double-occupancy rooms? How many businesses have no upfront prices?

Most of these examples stem from the underlying loss of what I call "management innovation"--to distinguish it from the amazing gains in clinical innovation driven by physicians and researchers in hospitals. Decades of excessive short-termism have withered hospital managers' desire and even ability to innovate. That's why few hospitals have innovation teams, innovation centers, R&D departments, or line items in their budgets dedicated to innovation.

Fortunately, in the hospital industry there is still some "long-termism," from which other hospitals can learn: children's hospitals always put long-term patient needs above short-term financial targets; academic medical centers overseen by academic physicians try to do the same; and a few faith-based hospitals have managed to preserve the long-termism cherished by their founding orders. The common theme here is an adherence to a superordinate--one might say sacred--mission that always trumps short-term financial targets: the care of children, the teaching of the next generation of healers, the continuation of a healing ministry.

Health care reform is about long-term value for patients, the antithesis of excessive short-termism. This means that, as heretical as it may sound, hospitals must question entrenched beliefs about the importance of 12-month budget targets and the inviolacy of bond ratings. They must--in action, not just words--put safety, quality, and service ahead of short-term returns, they must invest seriously in innovation, and when cost-cutting is necessary they must use patients' needs and clinicians' knowledge as their compass. Most of all, they must find and adhere to a superordinate mission and vision that keep excessive short-termism at bay. It's time to shift the paradigm from "no margin, no mission" to "no mission, no margin" and from "excessive short-termism" to "mission-focused long-termism."