Female sexuality: when asked to explain it, Freud threw up his hands in despair. Virginia Masters and William Johnson reported on it in The Human Sexual Response, studied it in action and declared it -- physiologically -- to be pretty much the same as men's (except for those multiple orgasms). Embryologists tell a neat little story about the near identity of the developing penis and the developing clitoris, each billed in adult life as THE organ of sexual sensitivity and expression. It turns out, though, that despite decades of study and centuries of speculation, we know surprisingly little about clitoral anatomy and physiology, especially how the nether parts and touch sensitive organs such as breasts communicate with the brain.

Anatomically speaking, the clitoris has a checkered history. Even after some of the best known anatomists of the 16th century, among them Falloppia and De Graaf, apparently discovered the clitoris, more prominent ones, such as Vesalius and Galen denied its existence. Since then, the anatomical pendulum has since swung back and forth although even recent anatomical textbooks (for example the 1999 edition of Last's Anatomy) do not always describe the organ, even while devoting pages of attention to penile anatomy. In this piece I will set aside the whys and wherefores of the clitoris' uneven history in order to focus on new anatomical findings about the clitoris itself, and how it is linked, neurologically to the brain. The questions resonate, of course, for our understanding of sexual function in women. Understanding clitoral anatomy is critical for medical reasons: what causes vaginal pain (a condition called dyspareunia), what are the long-term effects of genital surgery be it for rare cancers or genital cutting? When considering genital cutting, I think not only of the practice found primarily in some Middle Eastern and North African cultures, but also western cosmetic surgery (such as reduction of the pubic mound or shaping of the vaginal lips) and surgery on people born with altered genital anatomy, caused by one or another disorder of sexual development.

Over the last 25 years Australian urologist Dr. Helen O'Connell, has contributed importantly to our knowledge of clitoral anatomy. While most people (I hope) are familiar with the visible bit (called the glans) which looks like a mini-penis without the urethra running through it, it turns out that a larger portion of the structure runs underground. Beneath the surface, the glans attaches broadly to the vaginal lips and the pubic mound as well as to the urethra and vagina itself. Even in infants the nerve trunks (picture bundles of telephone wires) are large, and thoroughly connected to vagina, urethra, erectile portions of the clitoris and perineum (the bit of muscle that runs between the buttocks from pubic bone to tail bone).

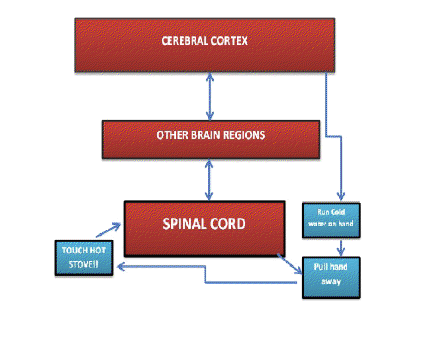

Beyond the on-site anatomy, though, run the remote connects, from the peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and brain. For example, touch a hot stove and a signal runs up a sensory nerve to the spinal cord which transmits the signal to a motor nerve, which in turn signals your arm muscles to pull away from the stove. All faster than a speeding bullet, and all without thinking. But the spinal cord also sends signals up to the brain. As these register you take conscious action, perhaps racing over to the sink and running your burnt fingers under cold water.

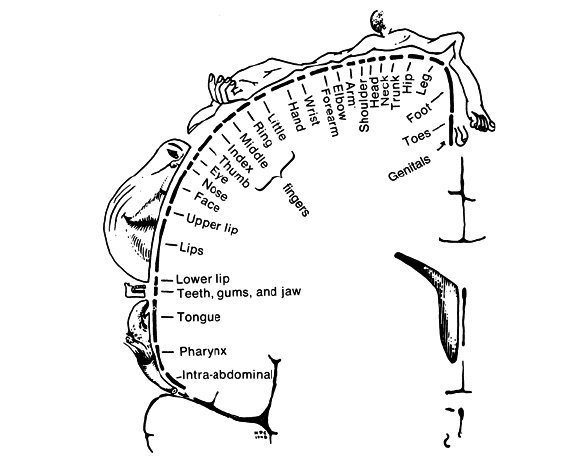

The sensory nerves that report on your hand and arm (or on any other sensitive body part) deliver their message to a specific place in the cerebral cortex, which then transmits orders for further movement. In the 1930s, Dr. William Penfield developed maps, in the form of pictograms (one for the sensory and one for the motor nerves, of oddly shaped and disarticulated body parts draped over the two-dimensional surface of the cortex. This pictogram became known as the homunculus. Look closely and you can see that at one end, beneath a grotesquely misshapen foot, is a tiny penis and testicles. No clitoris, no breast, no vagina, uterus, cervix or ovaries. Why? Because Penfield studied almost no female patients.

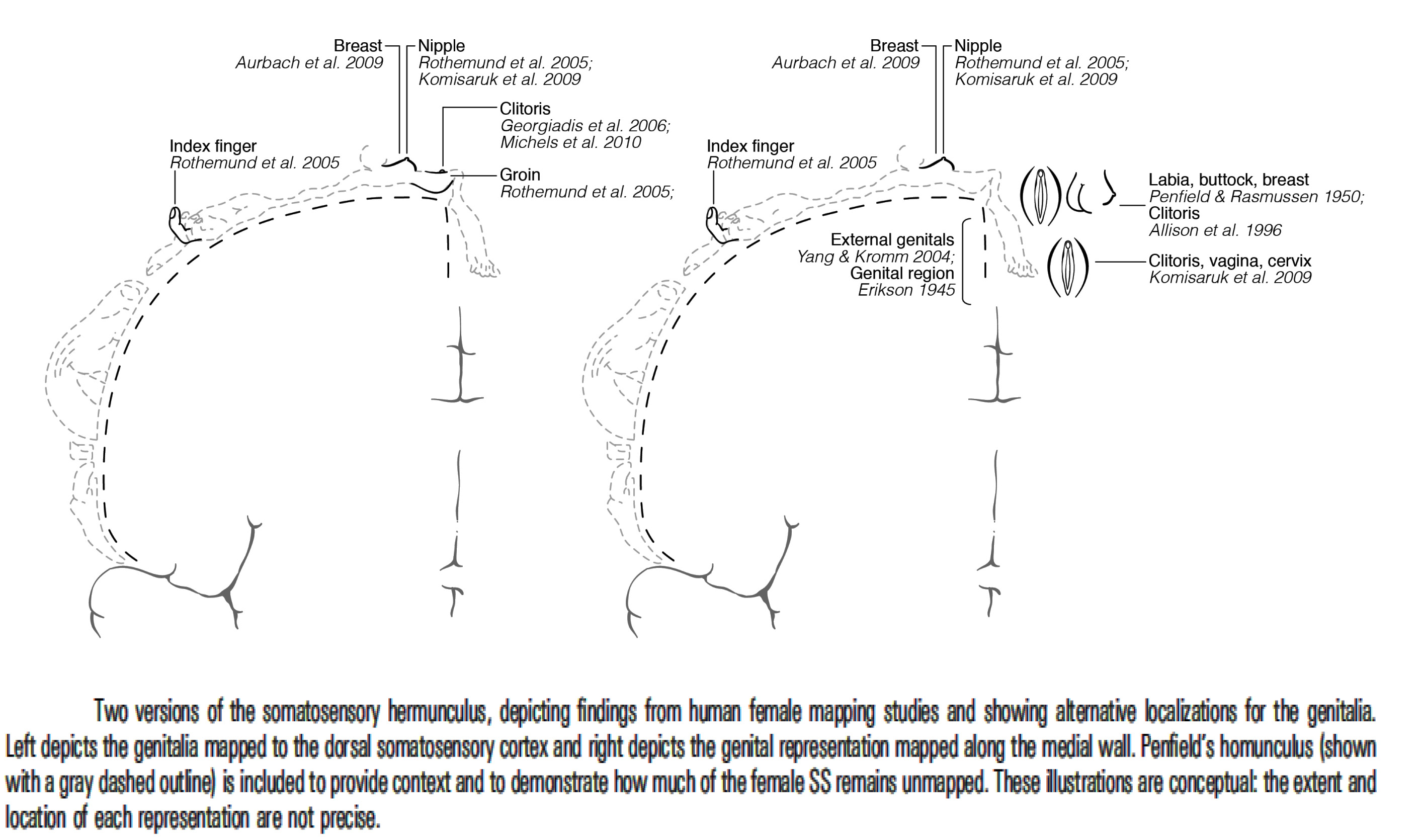

Surely, though, by now, this omission of critical knowledge about how female body parts experience and transmit sensation, both pleasurable and painful has been corrected. Not so much. A recent paper by neuroscientist, Dr. Gillian Einstein and her colleagues at the University of Toronto, Canada, reviews the still scarce information. What evidence they did find suggests that we need a HERmunculus, and that there are reasons to suspect it will differ from Penfield's map. For one thing, early results indicate that the large internally located bits of the female genitalia, described in such detail by O'Connell, may map onto a different portion of the cortex than the external bits. Furthermore, it seems likely that the hermunculus will change over the life cycle and depending on experiences -- including procedures such as mastectomy, or vaginal (including episiotomy) or clitoral surgery. Understanding more about the genital-brain connections would offer a better understanding of the chronic pain which can follow surgery and which can plague women and their partners during sexual interactions.

Penfield may have avoided studying genital sensations in women because he did not think female sexual responsiveness was properly feminine or normal. But that omission in his research mission has had the long-term consequence of ignorance about the hermunculus and the continued inadequate treatment of sexual pain and dysfunction in women.