As we come into the Holiday season, I find this a good time to give thanks for all the blessings that my family, my friends and most of us have, in one way or another. And it's also a good time to think about those that are less unfortunate than we are. And this includes the medically uninsured.

Lest you believe that being medically under or uninsured is not as bad as it sounds, we should remember that roughly 40% of Americans owe collectors for medical bills and that U.S. adults are more likely than those in other developed countries to struggle to pay their medical bills or worse, to forgo care because of cost, as a recent piece in The Atlantic highlighted. Which means that medical bills have become the leading cause of personal bankruptcy. And being under or uninsured quite literally leads to an early death. An analysis by Families USA noted that across the nation, 26,100 people between the ages of 25 and 64 died prematurely due to a lack of health coverage in 2010, placing the lack of insurance in the top 15 causes of death per the US DHHS National Vital Statistics Report.

No, being medically uninsured is not just a small issue. It's a very bad thing for many Americans.

And in case you also don't think it's your problem, think again. Remember, the uninsured do receive care... just eventually and very late. In addition to the moral and ethics precepts that we all should be guided by, the sick will receive care in our country regardless of insurance status, when in extremis or under catastrophic circumstances by law (for example, under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act or EMTALA). The costs of this care are eventually (granted via very circuitous routes) borne by all taxpayers.

The problem, of course, is that by being uninsured you have to wait until you are in extraordinary circumstances, very ill or disabled, to receive health care. And the uninsured generally do not seek nor can afford preventive medicine. So a sickness that could be treated conservatively at a modest cost early on (say glucose intolerance or hypertension) becomes one that is severe, with multiple damaged organs (advanced diabetes with microvascular disease or a stroke) that costs a small fortune to treat - and with poorer results to boot - when the uninsured patient finally accesses medical care.

And so we have created a system which encourages citizens to forego preventive care and early treatment, encouraging the transformation of illnesses that could have cost cents to treat into something that will cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Not to mention the many ways that the high number of uninsured decrease our nation's ability to grow the economy - driving up the cost of health care, reducing the number of healthy workers available, limiting tax revenues that could be put to work stimulating economic growth, and diluting the competitiveness of businesses and health care providers. All around, not very smart. Nor very ethical.

I am not trying to argue about whether it is right or not for the larger society, through its organized bodies, to provide for the health (and education) of its citizens, although I very much believe it should. What I am arguing here is that regardless of how people in our nation feel about the uninsured, the cost of caring for the uninsured when they eventually become sick enough will come out of our collective pockets. And when we do pay, we will pay for more than we would have if the illnesses were taken care of early or prevented altogether.

The good news is that thanks to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2010 (i.e. Obamacare) and an improving economy the number of uninsured nationally has decreased by about 10 million individuals, with the uninsured rate for adults under 65 estimated to have fallen from 16% to 11%.

However, recent data also suggests that these gains are not uniform. A recent analysis by the New York Times, using large sets of data from Enroll America and Civis Analytics, indicated that the medically uninsured tended to live in the South and Southwest, where the administrations of many of these states has opted to turn down federal funding to expand Medicaid coverage for low-income families. And they tended to be poor.

Poor, yes. But are the uninsured also jobless? In fact, it may come as a surprise that a large proportion of the nation's uninsured are active participants in the nation's workforce ... the freshly minted college graduate waiting tables at your favorite restaurant, the woman at the antique shop who sold you the 18th century French armoire, or the man at the full service gas station who plugged the leak in your tire last week.

So while it's true that lack of health insurance often goes hand in hand with unemployment, it, tragically, is also true that a large number of the medically uninsured do work. To understand this dynamic, we need a better grasp on the structure of our nation's employer and employee marketplace.

Nationally, 48.4% of employees work in firms that employ less than 500 individuals (defined as small business) and 34.3% work in businesses with less than 100 employees (i.e. very small businesses), per data from the US Census Bureau.

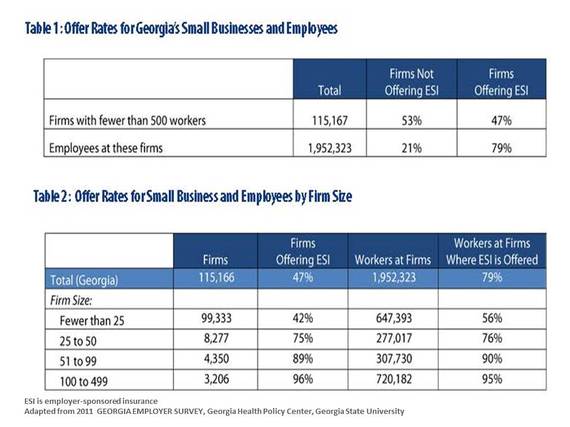

And the smaller the business, the less likely it is to offer health insurance. To illustrate let's use Georgia, a state that despite gains still ranks among the top ten states with the highest percentage of uninsured, according to an analysis by GeorgiaWatch. Data from the 2011 Georgia Employer Survey, conducted by the Georgia Health Policy Center at Georgia State University, indicated that 53% of firms with less than 500 employees did not offer employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) at the time. And the number of employees offered ESI decreased as the size of the firm decreased. In 2011, Georgia businesses that employed less than 25 individuals accounted for one-third of all employees in the state, but only 42% of these businesses offered ESI (Figure).

The high rate of uninsured and the low rate of ESI nationally is unlikely to improve in the short term without active intervention, such as a facile, accessible and transparent small/individual insurance marketplace, better education of the employer and employee population regarding the pros and cons of insurance coverage, and economic incentives and disincentives for small businesses to foster the offering of ESI, to increase employees to participation in those ESI programs offered, and to increase the offering and participation in health maintenance and illness prevention programs.

We need to stop thinking about the uninsured as "unemployed people without insurance" and see them instead as our working neighbors, colleagues, and employees who can get health care only when their problems become extreme or catastrophic ... which costs a lot more money to address than if they had been receiving preventive care ... which limits what we have available to do more economically productive things for our nation... and most importantly, leaves them both financially and physically poorly off.

We also need to recognize that the medically uninsured are everyone's problem. And that many of them are working folk too.