It sounds like some exotic story that you would find in a National Geographic magazine, but it's actually a story that many physicists are increasingly worried about!

For the last 100 years physicists have built exotic "atom smashers" to probe the innermost constituents of matter. Along the way they uncovered a bewildering number of exotic particles called "mesons" and "baryons," only to discover that they are all just groups of two or three basic particles called "quarks." Today we have a breathtakingly elegant mathematical theory called the "standard model of particle physics" that seems to explain all of the physics we see at the atomic scale.

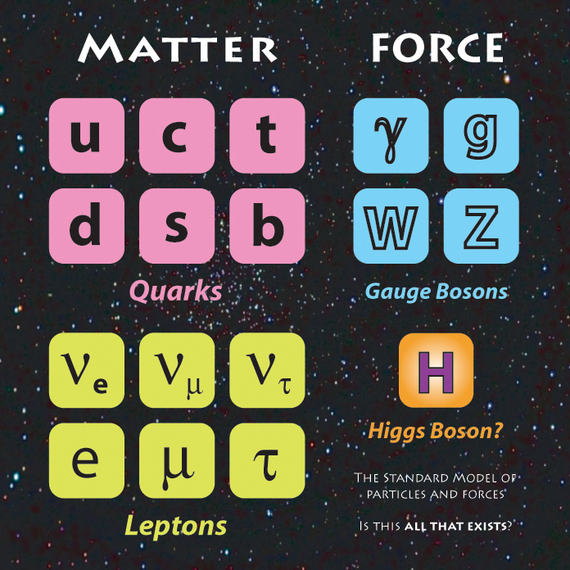

From a family of six quarks, six leptons and 12 gauge bosons, we can predict the properties of all known mesons and baryons, along with how they interact with one another to build up atomic nuclei, cause radioactive decay, and produce every natural phenomenon involving light and charged particles.

The particles and forces of the standard model (credit: GridPP.ac.uk)

Fifty years after its existence was predicted, the very last holdout needed to complete the standard model, the Higgs boson, was finally discovered in 2012. Whereas the other particles in the standard model explain the makeup of all composite particles, like protons, mesons and atomic nuclei, the Higgs boson explains why these particles have the masses that they do, and why the weak force is weak and carried by massive particles called the W+, W- and Z0.

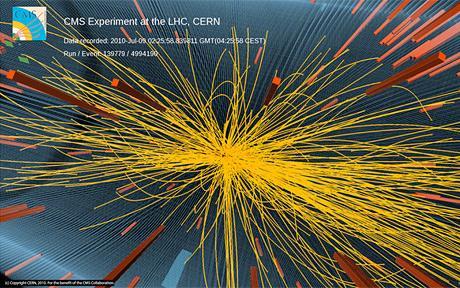

During all this time, teams of physicists working in the "data dumps" of billion-dollar colliders have sifted through terabytes of information to refine the accuracy of the standard model and compare its predictions with the real world (whatever that is!). The predictions always seemed to match reality and push the testing of the standard model to higher and higher energies. But at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, among the trillions of interactions studied up to energies of 7,000 GeV, no new physics has been seen in the furthest decimal points of the theoretical predictions and actual data -- not so much as a hint that something else has to be added to the standard model to bring it back in line with actual data!

One of many interesting collisions recorded by the LHC Compact Muon Solonoid detector (credit:CERN/LHC/CMS)

In the history of all previous colliders beginning in the 1950s, something new has always been found to move the development of the standard model forward. In the 1970s it was the discovery of quarks. In the 1980s it was the W and Z0 particles, and even recently it was the Higgs boson. All these particles were found below an energy of 200 GeV. But now, as the LHC has ended its first season of operation up to 7,000 GeV, a desperate mood has set in. No new particles or forces have been discovered in this new energy landscape.

Nada. Nothing. Zippo.

What's worse, theoreticians who have their lives invested in supersymmetry theory and the ever-popular string theory are worrying about abandoning much of this work if this empty energyscape persists to the limit of the LHC range, at 15,000 GeV. When the LHC resumes operation, it had better start seeing a handful of new partners to the quarks and other standard-model particles, or else theoreticians will have to come up with entirely new ideas not based upon supersymmetry or string theory!

The problem is that the proposed next-generation standard model, which is supposed to extend our understanding of quantum physics above 200 GeV, demands that there be massive partners to all the familiar standard-model particles. The minimally supersymmetric standard model (MSSM) requires a dozen new massive particles starting at an energy of 1,000 GeV. If these are not found by the LHC, theoretical and, by some accounts, inelegant explanations will have to be developed to explain "where they went." But there is another problem too.

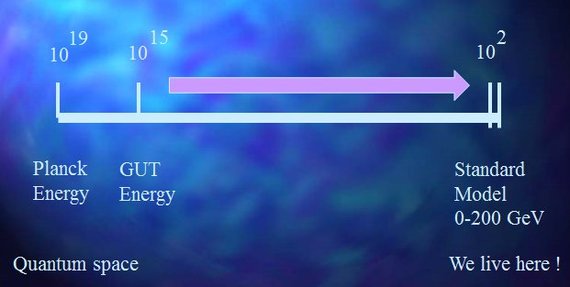

The Energy Desert

Most of the theories that go beyond the standard model provide ways to unify the strong force with the electromagnetic and weak forces. At some very high energy, they say, all three forces have the same strength, unlike their present circumstance, where the strong nuclear force is 100 times as strong as the electromagnetic force. The predicted energy is about 10 trillion GeV -- the so-called grand unification theory (GUT) energy. The theories also tend to say that between our world, at 200 GeV, and the GUT world, at 10 trillion GeV, there are no new particles or forces, hence the name "energy desert."

The energy desert, where 1 GeV of energy is about equal to the mass of a single proton (credit: author)

According to GUT calculations, if there were particles in the energy desert, the proton would decay much too quickly, and this effect would have led to there not being any protons in our universe today. That means no stars, planets, atoms, etc.! This energy desert is also required in order to keep neutrinos at such a low mass.

So the bottom line is that if, in 2015, the LHC discovers so much as one new particle, all will be well, and there will be huge parties around the world celebrating the new physics of supersymmetry. Legions of theoreticians will be able to return to working on supersymmetry and string theory with new data to think about.

But if no new particle is found, life will be much worse. There will continue to be no simple explanation for the existence of dark matter. Although nature favors simple theories, it will have decisively vetoed the simplest known theory that goes beyond the standard model. The LHC will have discovered that the energy range between 200 GeV and 15,000 GeV is devoid of new particles, and that the initial dune field of the energy desert has been traversed. But unlike the Sahara Desert, there are apparently no easily reachable oases of new particles to which physicists can target new generations of expensive colliders.

It remains to be seen whether the results from LHC after 2015 will confirm our greatest hopes or validate our worst fears. Either way, stay tuned for some exciting news headlines!