Co-authored by Ellen M. Snyder-Grenier

What does your name mean to you?

How would you react if someone took away your name?

As the 1970s ended, I changed my name to Tukufu Zuberi, which is Swahili for "beyond praise" and "strength." I took the name because of a desire to make and have a connection with an important period where people were challenging what it means to be a human being. So, you can probably appreciate how important names are to me.

In the collections of Philadelphia's Independence Seaport Museum is a large, leather-bound ledger. Old, unassuming, and rare, its now-faded pages document business transactions that took place almost 250 years ago: transactions that force us to consider what it means to have a name, and what it means to be human. In this third in a series of blogs inspired by the exhibition Tides of Freedom -- in which we explore the notion of freedom through the material culture of the African experience along the Delaware -- we offer that understanding the dehumanizing processes of enslavement is a window for understanding what's in a name.

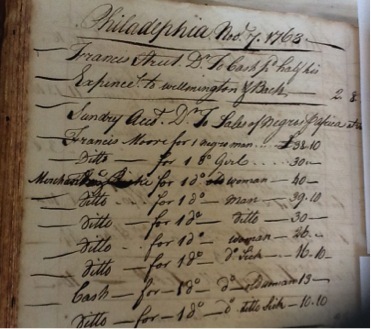

This ledger, which spans the time period from May 13, 1763 to July 2, 1764, bears the title, "Wastebook B" (Explore Wastebook B). In colonial times, a wastebook was a rough, daily diary of transactions; it was suppose to be discarded once it was recopied into a more formal ledger. "Wastebook B" lists the accounts kept by an unidentified Philadelphia merchant for groceries, liquor, dry goods, French lessons for his daughter -- and the enslaved.

Turn the pages, and you will find dozens of entries for enslaved Africans. These men, women, and children had managed to survive the unimaginable horrors of the Middle Passage. They had sailed up the last leg of that passage -- the Delaware River -- and docked in Philadelphia, the largest port in the British colonies.

Now, the Africans were about to be sold.

If you look closely at the entry for August 17, 1763 (pictured above), you can see that for slave sale entries, the white merchant does not write actual names. Instead, he writes, "2 negro men," "2 negro women," "2 negro women," "1 negro boy," "1 negro girl."

The words we choose to talk about people, places, and things are revealing. In this case, the words used by the white merchant to describe the shackled Africans before him -- words to which he likely gave no thought at all -- are disturbingly telling. They reflect the widespread, systematic attempts of dehumanizing Africans. It was a process that rationalized slavery by treating Africans as if they were less than human, and therefore acceptable to exploit as free labor like dogs and cows.

As the merchant dipped his quill pen in ink to write each entry for enslaved Africans in this ledger, as he formed each letter and wrote each word, he advanced the system of slavery. Mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters, people with proud families and family names, were now represented only by a descriptive term for the color of their skin: "negro" -- black. This was an important step in the process of enslavement; and required the enslaved to accept a brand not on their back, a brand based on their very name, a new taken from them in the process of enslavement.

In contrast, this page from Wastebook B lists the full names of the white slave traders who purchased the Africans. We see the name of Susannah [Riche] Badger, who charged the cost of "merchandise" -- six Africans -- to her account. Records show that Badger, a Philadelphian, handled business transactions for her husband (a ship captain who transported the enslaved from Africa to America) and her brother, Thomas Riche (a merchant who sold them). John Morris's name is also listed in full. Morris, the son of Philadelphia's mayor, deducted money from his account to pay for six Africans, who were probably the same people Susannah Badger had imported from Africa.

We can trace Badger and Morris in historical records because they, unlike the Africans, were named. Their names were recorded in account books and in legal documents; when they died, their names would be permanently carved in graveyard headstones. For the enslaved, it was a different story. While their masters would eventually rename them, it would usually only be a first name. And the only time it would ever be recorded, most likely, would be in a bill of sale.

In 1775 -- a year before the American Revolution -- radical writer and patriot Thomas Paine, then living in Philadelphia, looked out at the city's slave market from his window. The scene gave him pause. "That some desperate wretches should be willing to steal and enslave men by violence and murder for gain, is rather lamentable than strange," he said. "But that many civilized, nay, Christianized people should approve, and be concerned in the savage practice, is surprising." That same decade, a decade in which patriots fought for freedom from tyranny, slavery began to decline. The number of free blacks in Philadelphia began to grow, as would the abolitionist movement. Emancipation, though, was years away.

"Wastebook B" is a witness to our American past. In it, a merchant's careful writing in now-faded ink -- "negro men," "negro women," "negro boy," "negro girl" -- raises questions in the present about power, inequality, and injustice, what it means to be human, and who decides. Un-naming was an insult to the humanity of the enslaved Africans and as such an insult to what it means to be human. The ancestors of these un-named Africans would rise from the oppression of enslavement and reclaim their identity and save freedom and liberty from hypocrisy. The fight to restore dignity to the enslaved by emancipation was a fight to redefine what it means to be human.

My name means so much to me that I changed it in solidarity with the social movements of the 60s and 70s. What does your name mean to you?

Next installment: Emancipation

Ellen M. Snyder-Grenier is an independent curator, exhibition developer, and writer, and principal of REW & Co.

Image is a page from "Wastebook B," 1763-4, Courtesy of the Collections of the Independence Seaport Museum, gift courtesy of J. Welles Henderson [1971.044.021]