"For a collective censorship, for an oppressive mentality, making films about politics that seem very progressive, very revolutionary is much more comfortable than making films that question you, as a human being. And that's where the real censorship lies." Meeting Yousry Nasrallah face to face is a true luxury. Not because the Egyptian filmmaker makes himself precious -- quite the opposite really -- but because Nasrallah's extraordinary insight, languid expression and sensual voice all combine to create the most perfect conversation.

"For a collective censorship, for an oppressive mentality, making films about politics that seem very progressive, very revolutionary is much more comfortable than making films that question you, as a human being. And that's where the real censorship lies." Meeting Yousry Nasrallah face to face is a true luxury. Not because the Egyptian filmmaker makes himself precious -- quite the opposite really -- but because Nasrallah's extraordinary insight, languid expression and sensual voice all combine to create the most perfect conversation.

Sitting across from him in the Dubai sun, during the recent Gulf Film Festival, I couldn't help but imagine that he'd always occupy the seat at the head of the table in any personal "who would be your dream dinner party guest" scenario. With music playing, the breeze of the air conditioning from the bar's open doors cooling down the sweltering desert air and the smell of scented tobacco wafting from the hookah lounge next door, it all seemed like a mirage, a culturally stimulating, wonderful mirage.

This was not my first time interviewing Nasrallah, but during our other talk -- at last year's Abu Dhabi Film Festival where his latest film After the Battle screened -- I remembered him as being more mysterious, somewhat cryptic. In Dubai instead I found an open, generous and (forgive my impertinence) bewitching man, perhaps because the artificial familiarity of Twitter had helped me to believe I understood him and his work more. Putting aside religious beliefs, I'll never forget Nasrallah's touching words on the day Pope Benedict XVI left the pontificate: "Pope lands in Castel Gandolfo. When a man declares himself unable to lead, and resigns, he becomes truly great and an example to follow."

But ultimately, it all boils down to Nasrallah being a complex man of many layers, much depth and inspired heights. I would hope to interview him a thousand times, and his words will keep cinema alive forever for me, similarly to the stories of The Arabian Nights, which he himself so masterfully reset into contemporary Cairo for the film Scheherazade, Tell me a Story. When asked to describe himself, Nasrallah said "Film maker, a good one." Could not have put it better myself.

After the Battle is so very personal for a woman to watch. How do you as a filmmaker, connect so beautifully to women's issues?

Yousry Nasrallah: You start out by a very simple feeling, it's not even something that you have to reflect upon too long, once you start dealing with women as equals, as human beings... I don't idealize women, in any way. I don't think there is anything idealistic about it, nor do I consider them special in any way. I feel they are part of humanity, a part that I happen to like and that intrigues me a lot.

But most men don't know how to do that.

YN: Maybe I'm not like most men (laughs). When you write, or when you make a film -- the first thing about filmmaking for me -- is never treat a character as being less intelligent than you are. It's a way of also respecting your audience. So as not to appear as someone flaunting myself to be adorable and respecting human rights, respecting women and whatever, but at least somebody who knows what cinema or drama is.

What appeals to you in a story?

YN: A story about people who are not identical to me -- this has always been a theme in my films. I go to places that I'm afraid of, people I don't know. Starting from the third film which was a documentary called On Boys, Girls and the Veil (Sobyan wa banat) and then The City (el Madina) and The Gate of the Sun (Bab el shams) about Palestinians, I've always been going places I'm not familiar with and trying not to conciliate, but simply understand. And I think maybe the relationship to women is the same. In After the Battle, there's something in the women, the opposition between a very romantic, idealistic woman and a very down-to-earth, very pragmatic, survivalist woman, with no cynicism at all, I don't like cynicism. Shrewd, slightly perverse, they are all things that I find very attractive in the character of Fatma, and the confrontation between one very unpractical and one very practical reality sounded like good drama to me.

Do you think cinema could change the world?

YN: No, because it's pretentious. If you set out making a film thinking that you're going to change the world then you're in big trouble, because it won't change.

Do you think that Egyptian, Tunisian and now Syrian filmmakers are going to get stuck in making films about the revolutions?

YN: If you look at cinema anywhere in the world, it has always dealt with the present. Even if you make a historical film about Elizabeth I it always has resonance in the present and the present being what it is. Rather than be stuck in depicting a reality that does not exist I think what the revolutions have done is allowed filmmakers and artists to really be part of the 21st century. I don't think anybody will buy slogans, I think that people need cinema to be what it is supposed to be, telling them good fairy tales that will allow them to sleep.

YN: If you look at cinema anywhere in the world, it has always dealt with the present. Even if you make a historical film about Elizabeth I it always has resonance in the present and the present being what it is. Rather than be stuck in depicting a reality that does not exist I think what the revolutions have done is allowed filmmakers and artists to really be part of the 21st century. I don't think anybody will buy slogans, I think that people need cinema to be what it is supposed to be, telling them good fairy tales that will allow them to sleep.

You've tweeted about the talented filmmakers you've mentored here during the Gulf Film Market, treated them as equals, that's not something you get often from master filmmakers.

YN: Twenty five years ago I made my first film and I was treated with respect, I wasn't a battered child. Or maybe I was... Talent is something you have to respect, even if ultimately you end up detesting the person because you are jealous of them. But at the end of the day -- and I swear I'm not patronizing at all -- if you see talent, you respect talent. When I write a script I give it to my friends to read and discuss, they're my mentors. You don't make a film alone, even when you do.

The biggest challenge for filmmakers from the Gulf?

YN: We're under the impression that Gulf people are pampered, they're rich and that filmmakers in the Gulf, the reason they don't make films is probably because they are too spoiled to make films. And then you discover the bitter reality that they're not even funded here. People prefer giving money to American and international productions rather than help young filmmakers here. You have an incredible opportunity in the Emirates, it's a culture we don't know anything about, it's a language we have hardly heard at all, it's a landscape which we are not at all familiar with, it's like reinventing cinema. It can only be a win/win situation if you start encouraging a thing like this.

There is this misunderstanding that if you come from the Emirates you must be rolling in dough.

YN: Exactly, whereas they're as poor as any African filmmaker!

What's going on with Egyptian cinema?

YN: If we're talking in terms of industry, it's in big trouble, but creatively, there are films being made, and some wonderful ones. I don't know if you've seen Hala Lofty's film, she's a young woman filmmaker who made a film called Coming Forth By Day, Ahmad Abdalla who made Microphone just finished a new film called Rags and Tatters, he's taken ages to finish it but I hear great things... Filmmakers make their films regardless of the industry, but the industry itself is in bad shape.

What's next for Mr. Nasrallah?

YN: Either I stay in Cairo and cook, or stay in France, just to keep away for a while from the political pressure. You know, you make great films when you talk about relationships of the individual with the universe, with God, with whatever, who am I, where I'm going -- this is what cinema is about. And somehow you are forced to stick to politics and political issues constantly. Actually, in a repressive society you don't exist as a person, you're a spokesperson.

I don't see a lot of cooking in your future...

YN: Are you a fortune teller? (laughs) I love to cook, you know you cook and you get the same kind of response you get for a movie! It's good, it's delicious, it's wonderful, or it's lousy. Come to Cairo, I'll cook you lunch.

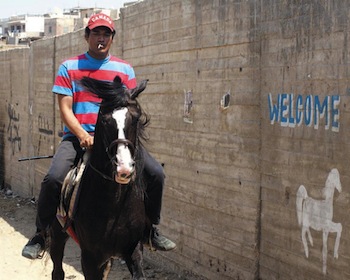

Photo of Yousry Nasrallah and still from After the Battle all courtesy of the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, used with permission