We are fast becoming a world of refugees. Most of us breathe, work and survive in a place that is not where we were born. Yet someone like me, one of the lucky ones, can choose to go home again, even if just to discover that the place I remembered from my childhood no longer exists.

The Palestinians are not so lucky. There are multiple generations born outside of their homeland and we all know that a world which does not learn from past history is bound to repeat the same mistakes. Today, Syrians, Iraqis, Afghani, Sudanese and perhaps soon the Egyptians are all discovering a fate not very different from that of the 1948 and 1967 displaced Palestinians.

And that should be worrying us. Or least pushing us to know more.

In his fascinating documentary A World Not Ours, and the short 'Epilogue' titled Xenos which just premiered at this year's Berlinale, filmmaker Mahdi Fleifel shows us his very personal connection to the refugee camp of his youth, Ain el-Helweh in Lebanon. He manages to teach without preaching and in the process entertain us, with a splendid soundtrack, great insight and hidden humor. While abstract ideas like the Palestinian "Right of Return" have become the proverbial carrot-on-the-stick used as a smokescreen to stall and avoid the real issues, Fleifel's films get to the heart of the matter, and tackle the issues head on, with great humanity.

I first met Fleifel at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival which supported A World Not Ours through its SANAD fund and where the film won the Black Pearl Award for Best Documentary in 2012. Ran into him again at the Dubai International Film Festival where he was beginning to plant the seeds for a new project and a crowdfunding campaign that would help him achieve eligibility for the Academy Awards in 2015.

I'll admit I'd resisted watching his film because I feared it would erode at what little hopefulness I had left, regarding the Palestinian cause. I should not have, because it turns out Fleifel infuses his truthful views with such wisdom, one can't help but feel there is much to look forward to. As long as Palestinian artists continue their cultural resistance, peaceful but constant, they'll achieve so much more than politicians ever could.

Following, Mahdi Fleifel shares his thoughts on crowdfunding, inspiration and Abu Eyad, the friend he tried not to leave behind.

You currently have a campaign on Aflamnah, the crowdfunding site. What are you hoping to achieve with it?

Mahdi Fleifel: I would love for the film to get more exposure in the US. Despite the fact that it has done so well at festivals, even some US festivals, it has been very hard to break through the barriers of 'Oh, here is just another Palestinian film'. And our film is not that, it's really just a film about family, memory, childhood, and friendship. It's about more universal things than merely a political situation.

What was the lightbulb moment that made you decide to turn the years of shooting video with your dad into a documentary?

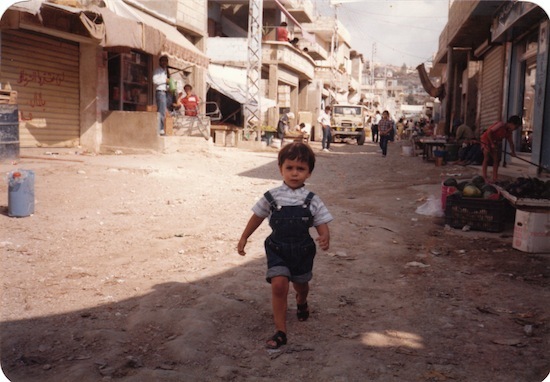

Fleifel: I'm not sure there was one particular moment, more years of frustration! Living in Denmark and visiting Ain el-Helweh each summer I always found it hard to explain to my classmates about the place I was from, the place I had just spent my holidays. While they would return with tales of club-med or the south of France I would tell them about chasing cats in alleyways and playing with Kalashnikovs. I would try my best but they could never properly understand this place. Then, when I was older, I started making fiction films in school. All of of these dealt with issues of identity, I think I was trying to explain once more where I was from and who I am. Despite some success with the shorts, I never felt I was telling the story I wanted to. Finally, in the summer of 2010, I went to the camp to research for a fiction feature, an adaptation of Spike Lee's Do The Right Thing, set around my uncle's sports shop during the 1994 world cup. I shot continuously for weeks on end and collected my father's old VHS tapes from around that time. On returning to London I sat down with my editor to cut a teaser and realized that I actually had everything I needed to tell the story I had wanted to tell all along - the reality would be far more satisfying than fiction. From then it was just a case of finding the story amongst all those hundreds of hours of footage. So maybe there was a lightbulb moment, but it certainly didn't come easy!

A filmmaker from Syria recently said to me, during an interview, "childhood is not a geographical place." Do you think that perhaps refugees are stuck in the plight of the child, forever trying to reconnect with their homeland because of what it represents, more than what it actually is?

Fleifel: I think this is very true, yes. In fact, as an Arabic speaker, if you go to Ain el-Helweh and speak to people there you realize that they have a dialect that is more or less unchanged since the time they were forced from Palestine. The actuality of Palestine today is so far divorced from what people are aspiring to that it can lead to despair, when you look at what happened to Abu Eyad I think this is clear. I often wonder what would happen if, one day, the people of Ain el-Helweh and all the other camps were told they were free to go back. What would they do? How do you undo Exile? I'm not sure if that is even possible...

You clarify so much in your films about the Palestinian struggle, and I believe the answer to the issues of this world lie in the hands of filmmakers. So what is the solution, for the Palestinians, as a whole people?

Fleifel: I don't think I know! I've always struggled since making this film to keep the line between film-maker and politician very clear. From a personal perspective, I don't see a lot of hope, especially for the refugees. They are pawns in a bigger game, a demographic threat to Israel and something to be traded. What I would like to see is a country where both people could live together with justice and peace. To me this would be a more realistic solution than to keep talking of a 'two-state-solution', which in essence is merely a Kafkaesque term, a way to keep 'kicking the can' down the road and postpone peace.

In Xenos, your 'Epilogue' to A World Not Ours you manage to show, in just over ten minutes, the results of ignoring a refugee situation, and how global a seemingly local problem really is. What is happening with Abu Eyad these days? And is there a solution to his situation?

Fleifel: After being deported from Greece Abu Eyad was sent back to Lebanon. Then, when AWNO played at the Berlinale in 2013, we managed to get him a visa to come present the film in Berlin and he decided to stay. Today he is once more facing deportation to Lebanon, so things aren't so great for him. I really don't know what the solution to his situation is. He didn't actually want to be in Greece, he's not really having a great time in Germany at the moment (they are not allowing him to work or study while his papers are in process). He just wants somewhere where he can work and have a family. As crazy as it seems, going back to the camp might actually make him happier but it certainly isn't a solution, and especially now that the whole country, Lebanon, is turning into a refugee camp with what's happening in Syria. The only real solution will come when his rights are recognized by someone, whether it be the Lebanese, the EU, or the Israelis.

Everyone talks about your soundtrack. How did you come up with the songs in your film?

Fleifel: From the outset I was determined not to make a 'typical' Palestinian film, and music was central to this. I also wanted to reflect the real influences in my life. While my parents may have listened to traditional music at home, it's not what I grew up with. A lot of my musical choices come from being a huge Woody Allen fan, a lot of the jazz comes from his soundtracks and, despite being from another part of the world, is from the era when my grandfather was exiled from Palestine to the camp in Lebanon so it's actually quite appropriate!

What are the lessons for the next waves of refugees which can be learned from the Palestinians displaced during the Nakba in 1948 and in 1967?

Fleifel: There's a long wait ahead of you!

And three words that describe you.

Fleifel: Handsome, funny and chubby (slightly).

Images courtesy of Nakba Filmworks, used with permission