As a child, Byron Pitts was functionally illiterate and spoke with a stutter. Today, he is an Emmy-winning Chief National Correspondent for CBS News and Contributing Correspondent to 60 Minutes. I had the opportunity to chat with Byron recently about his rise from illiteracy, the importance of parental involvement, and his proudest moment.

Earl: You were deemed "functionally illiterate" until age 12. How did you make it through school without knowing how to read?

Byron: I hid in plain sight for the first several years of my education in school. It was sadly quite easy, because I wasn't a discipline problem and because I attended the same school as my older brother and sister. And my mother was actively involved in the school -- she was a PTA parent.

There's a school of thought that children learn to read until about age seven. From seven on, they read to learn. And so the assumption is that I just missed something in those early stages of reading. I fell behind and kept falling behind.

Earl: How did that change?

Byron: I started failing math. The school tested me to see why I was struggling and found out I couldn't read the directions.

I was tested further and it was determined I was functionally illiterate. At the time, there weren't many resources at the school to help someone like me, so they just put me in the basement with boys who were primarily discipline problems.

One afternoon, I was watching television and there was an ad for a reading machine. It said that this machine could help adults who didn't know how to read. So I thought, if it could help them, maybe it could help me.

At this point, my desire to learn to read had little to do with me and more to do with my mother and wanting to make her proud and not wanting to cause her further embarrassment.

So, my mom calls this program in D.C. Basically, it was a small microfiche machine. It started with the alphabet, with the consonants and the vowels, sentence fragments, and built me up. Like stripping down an old car and building it over again, reinforcing the notion that I had missed something those first seven years.

Earl: It sounds like your mother and grandmother were both so active and involved. Do you have any thoughts about why more parents don't take that same approach?

Byron: In my mother's case, she clearly understood the value of education. My mother was a seamstress -- then she went back to college after my sister was in college. She insisted that all of her kids go to college. Even though she didn't have access to education, she still valued it. It's a value system you have to have and you have to insist upon.

Earl: Currently, Reach Out and Read -- and several other literacy organizations -- are at serious risk of losing their federal funding. Why is it important to invest in literacy programs like these?

Byron: These programs are invaluable. They don't just improve someone's life. In many instance, they save a life. I say that not based on things I've read or stories I've covered. But -- from my own life experience.

Because of the handful of educators, my family, and the resources that my mother was able to scrape together, I finally learned to read and that saved my life. I was destined for an early grave or a life in prison.

What's the saying -- Pay me now or pay me later?

Earl: In your book, you talk a lot about the influence of your mentors. Why is it so important for young people to have mentors to help shape their lives?

Byron: It seems to me that all of us should have skin in the game, that all of us have something at stake. I don't know of a single person I've ever met who could say, "I made it on my own."

My grandmother used to say the only way that God can give you more is if you open up your arms and give away what you have. The wider you open up your arms, the more you can take in.

Earl: After everything you've been through, what do you consider to be your proudest moment?

Byron: As a professional journalist, I've won all the awards you can win. But the proudest moment in my life was when I was finally brought a note home from school that I was able to read to my mother out loud. She cried and I cried. Tears of joy.

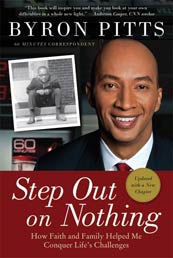

Byron Pitts's autobiography "Step Out on Nothing" was published in 2009.