By, Kuda Chitsike

Last month, Zimbabwe ramped-up legal measures to end child marriage, a hopeful sign for a dire problem.

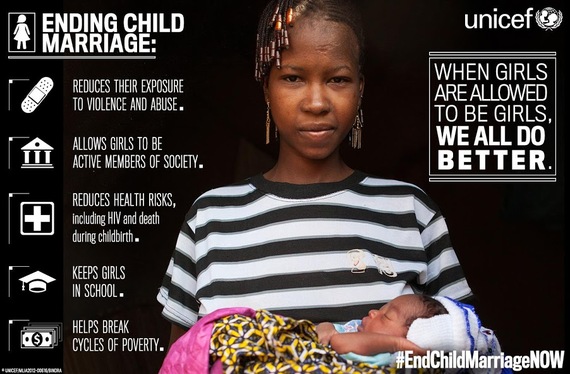

Child marriage is widely recognized as a violation of children's rights, and it is generally described as the marrying of (primarily) girls under the age of 18. According to UNICEF, in Southern Africa 33 percent of women between the ages of 20 and 24 were married in childhood. It is direct discrimination of the girl child, who, as a result, is often deprived of her basic rights to health, education, development, and equality. It also exposes girls to intimate partner violence and isolation from economic activities which have long lasting psychological consequences. Tradition, religion, patriarchy and poverty continue to fuel the practice of child marriage, despite its strong association with adverse consequences for girls.

For more than a decade there has been a sustained and dedicated effort by policymakers, government ministries, U.N. bodies, international and local non-governmental organisations, community-based organisations and individual activists to end child marriage in Zimbabwe. All these efforts culminated in a case being brought before Zimbabwe's Constitutional Court in January 2015, with the judgement coming a year later that finally outlawed marriage before 18 for both girls and boys.

The case was brought by Loveness Mudzure and Ruvimbo Tsopodzi, (two former child brides), who, through their lawyer, Tendai Biti, took the courageous step of challenging the Marriages Act, which had allowed girls to marry before the age of 18. This case was brought with the support of non-governmental organisations, Roots, Veritas and Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR).

The judgment is very welcome as the Marriages Act set the legal age for marriage at 16 for girls and 18 for boys, which contradicts the Constitution that promotes gender equality. Zimbabwe followed in the footsteps of other Southern African countries that have set 18, and, in some instances 21, as the legal age of marriage. Most recently Malawi did this, but many of these countries have exceptions where girls are allowed to marry as early as 15, if they have parental consent. As we celebrate this judgment, there is a need to look at the issues of child marriage and consent to sex holistically and educate society because the issue is interpreted in a confusing manner in our conservative and religious society.

The Criminal Codification and Reform Act states that girls under 12 cannot consent to sex and sexual relations at that age are always regarded as rape. This changes however, for girls who are above 12, but under 14, at which point the perpetrator, shall still be charged with rape. However, the law further states that, if the male can prove that the girl was capable of giving consent, and that she gave her consent, then the perpetrator cannot be charged with rape but with "sexual intercourse with a young person." The law goes on to states that if a girl above 14 but less than 16 has sex with her consent, it is not rape but "sexual intercourse with a young person." Girls over 16 can consent to sex but cannot marry until they are 18 according to the judgment.

The law is effectively saying it is permissible for girls to have sex at 16, and, if she is in love and/or becomes pregnant, and wants to get married, she cannot. This gets more confusing in reality. Culturally in Zimbabwe, having sex and becoming pregnant is an acceptable path towards marriage, but having unmarried sex and is highly disapproved of. The judgment now creates a clash between the law and age-old culture, but also removes discretion. Are we denying those over 16 who can consent to sex but are under 18, have parental consent, and want to get married, the right to do so? This lack of discretion is not the case in other Southern African countries, and the judgment seems a case of overkill for the problem of child marriage.

Although poverty is primarily blamed for driving the practice, there are other factors driving child marriage in Zimbabwe. These range from religious practices, lack of discipline at home, abuse, and family disruptions to over sexualization of the girl child. However, the main driver of child marriage is deeply rooted in the dignity of the family. In order to protect the family honor, as long as the girl is married the circumstances that preceded or led to the marriage are forgotten. According to research in one district in Zimbabwe, one woman stated that her standing in society is much better as a mother to a married child, whether over or under 18, rather than a single mother, regardless of the circumstances. The other women agreed, they talked about their dignity, (emphasis intended).

Another said "if she is sexually active at 13 how do I stop her from having sex and getting pregnant repeatedly? It is better for her to get pregnant when she has a husband even though she is young. I do not want the responsibility of looking after her and her child while the father is free to do as he wishes. As she has started doing grown up things, she must take responsibility for her actions and stay with the man who made her pregnant."

The views of these women are not uncommon, and highlight a problem with the law as it is now to be applied. Whilst it is commendable that there is a legal power to prevent child marriage, the law must also take cognizance of reality and the fact that there are exceptions. The judgment is part of an effort to stop families from marrying off their daughters at an inappropriate age, but should not also penalize the girl child unnecessarily.

Clearly there remains much to do, and little to do with the law. There is need to look at the legal system as a whole and propose a set of holistic legal and policy reforms that review the landscape of laws impacting on women and children. A broader range of policy alternatives and more sophisticated understanding of multiple strands of law and innovative legal strategies can converge to prevent child marriages.

Kuda Chitsike is Director of Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU), an independent, non-partisan, non-governmental organization with a mission to provide high-quality research on human rights and governance issues, particularly those pertaining to women and children as empirical evidence for advocacy to influence relevant and appropriate policy change. Kuda is a 2015 Eisenhower Fellow, a premier global network of leaders from all sectors working to better the world.