"Look for the woman in the dress. If there is no woman, there is no dress."--Coco Chanel

"Fashion fades, only style remains the same."--Coco Chanel

Though many in my family will disagree, my mother was not a great natural beauty.

Her nose lacked bone, her hair was thin and, after her one and only pregnancy, she lost her waist.

Childhood diphtheria and malnutrition in the Deep South of the Great Depression left her with a fragile spine.

She and I inherited her mother Abalena Boleman's knobby hands and arthritis, and it came early to both of us. One of the things my mother always told me is that the only way truly to tell a woman's age is by looking at her hands and, alas, she was so right. Till her death at 72 due to a crafty and perseverant form of cancer, her complexion, figure and bearing were all those of a much younger woman: the phalanges of her fingers told a different story (as do mine, now, at 61).

In her youth and in middle age, my mother wore kid gloves in a palette of colors, all just one size too small for me. In late photographs, just before cancer stole her final bloom, she cradles one hand in the other. We both knew too that, to lessen the appearance of veins and swelling in the hands, you must raise your arms above your head for half a minute and, voila, your hands will appear a decade younger.

My mother was not, though, vain in the least. Her beauty, and her lifelong fascination with fashion, with what must really be termed elegance, had to do with aesthetics and self-respect, not vanity. She, herself, was her own most memorable work of art.

Though she came up and out of a tiny, upstate South Carolina hamlet, population 100 at most, she had an uncanny eye; an unfailing, unwavering instinct about what objects, what clothing, what design, what manmade creation, what-so-ever . . . was sans-pareil.

When it came to what she selected to wear--her make-up, her jewelry, her hats, her gloves, her scent--she never, as long as I knew her, put a foot wrong.

And though she bequeathed me, through dumb genetics and, then, ceaseless training, her gift for language, I believe that, as a daughter, as the woman who might have been her heir in terms of self-recreation, I was a stunning disappointment.

Doomed from the start, as it were.

From birth, a long-limbed, angular creature made more along the lines of my father, I was not, to a stranger's eye, her biological kin. I shot up to 5'7" and could "eat ice cream off her head" (as we say in The South) from the age of 14. And then, too, I rebelled, openly and very early, against her personal culture of Chanel suits and scent, Charles of The Ritz make-up, three-inch heels, merry widows and garter belts and nylons, and her perfect French twist.

Ironically, we wore the same dress size and so, through the 1960s and 70s, when she was wearing Gucci and Pucci (would that I had those dresses now) I, some 31 years younger than she, could wear clothes out of her wardrobe. On me, they fell above the knee.

When I think of her, dressed to go out--and a day never dawned that she did not begin with her eyelash curler, her mascara, her light foundation and her drop-dead-beautiful lingerie--I think of her in the clothing of the very early 60s.

She was then, in her 40s, at the height of her beauty, at the height of her creative powers and, not incidentally, living in Europe, where she had scope unheard of in then-still-provincial California, where I grew up.

In Greece, a humble tailor would copy, for a song, anything out of the latest issue of Vogue. In Paris and Rome--and even in Scandinavia, where she bought dresses made by Marimekko, and wore them over tight black cropped trousers, with flats--she was in heaven.

My parents were, patently, poor. My father was a Fulbright scholar. There was never any real money. But money was not at all essential for my mother. She would find the one leather craftsman in Florence making a copy of a $2,000 French purse, and she would carry that Florentine bag, tucked away lovingly into its fabric-carrying sack at night, for the rest of her life.

Shopping, for her, was always so much more about simply running garments through her hands, inspecting the stitching, studying line and color. And this, she taught me too to love. She and I were surely the bane of many a department store clerk, as we "shopped" like two ascetics at a feast. To go see the new seasonal collections was a ritual for us, usually interrupted by lunch at Neiman Marcus (in Atlanta, just for instance), but rarely resulting in purchases.

Today, I continue this rite alone, as I have never met another woman with my mother's visceral joy in simply "grazing couture." I will go--as I do now--to Century 21 or Off (Saks) Fifth (Avenue), for times are decidedly tough in 2013's New Jersey, and revel in what's just been brought in from London or Milan or Paris.

The other day, slumming in my faded yoga gear, as usual, with not a smidgeon of make-up on my face and no scent--my Mother would decant her Chanel into an atomizer, spray it, and then walk through it: none of this dabbing behind the ears for her--I spotted a woman in her 70s darting about, several expensive (for Century 21) garments draped over one thin arm.

A buyer. From The City.

We made eye contact and, as I watched, she snapped up, one after another, the few pieces that would have met my mother's approval. She moved very rapidly through the couture section of the big box store. Very little pleased her. But, occasionally, she would stoop upon a hand-beaded, tulle over-blouse or a severely tailored riding jacket. She selected the very things I'd just been fingering with pleasure.

I was so happy just to watch her.

When my mother received her copy of Vogue every month in the mail, we would sit next to one another on her pale-blue Chippendale sofa (perhaps a Revival piece, but tant pis: it's a beauty even now), and go through the issue page by page.

We never skipped a page; never forged ahead. We were not, at this point, reading the magazine: we were devouring it.

The ads were always as important as the features; the clothing, and accessories, and hair-styles, and make-up were what she was after; what she was keeping up with; what she was showing me. There was always running commentary; critical response to this, that, the other. After her return from Europe, and the brief pleasure of the inner city in 60s Chicago, where my father took a faculty position and my parents had a lively social life they returned, out of a sense of shared duty, to The South, where my mother found herself, once again, in a part of the world where her particular gifts were invisible.

If the high point of your day is a trip to the local Winn-Dixie or Piggly Wiggly for sweet corn and center cut pork chops, will you still have the desire to put on your make-up and stockings and scent?

Well, Dear Reader, she did, taking me along with her--in my perennial jeans--Tonto to her glamorous Lone Ranger, whenever I was home.

The point was, I "saw" her; I always saw my mother. To me, the work of art she was was never "in vain," or effort wasted, or something of a lesser genre than, say, epic poetry or the ballet or painting in oils. I appreciated her for the modern Geisha she was. Yes, she could recite dialogue from Shakespeare and play Gershwin, beat anyone anywhere at any time at Scrabble, and cook ᅢᅠ la Julia Child . . . but always in Dior Red lipstick.

My favorite of the great Coco Chanel's quotes reads: "Elegance is refusal." And I believe this is what my mother embodied: a firm and flamboyant refusal, all her life, to be just the girl from Townville, South Carolina; just a woman who fell in love with a man who could give her (for the most part) "only" love; just a middle-class American woman of the second half of the 20th century, with a second-rate university education, doomed to grow up and live out most of her life in a country (she felt, and I also believe) to be largely without style, without elegance.

Chanel, again: "If you were born without wings, do nothing to prevent them from growing." My mother went so much further than that. Born with her mother's graceless hands, she would raise them above her head, count to 30, and take flight.

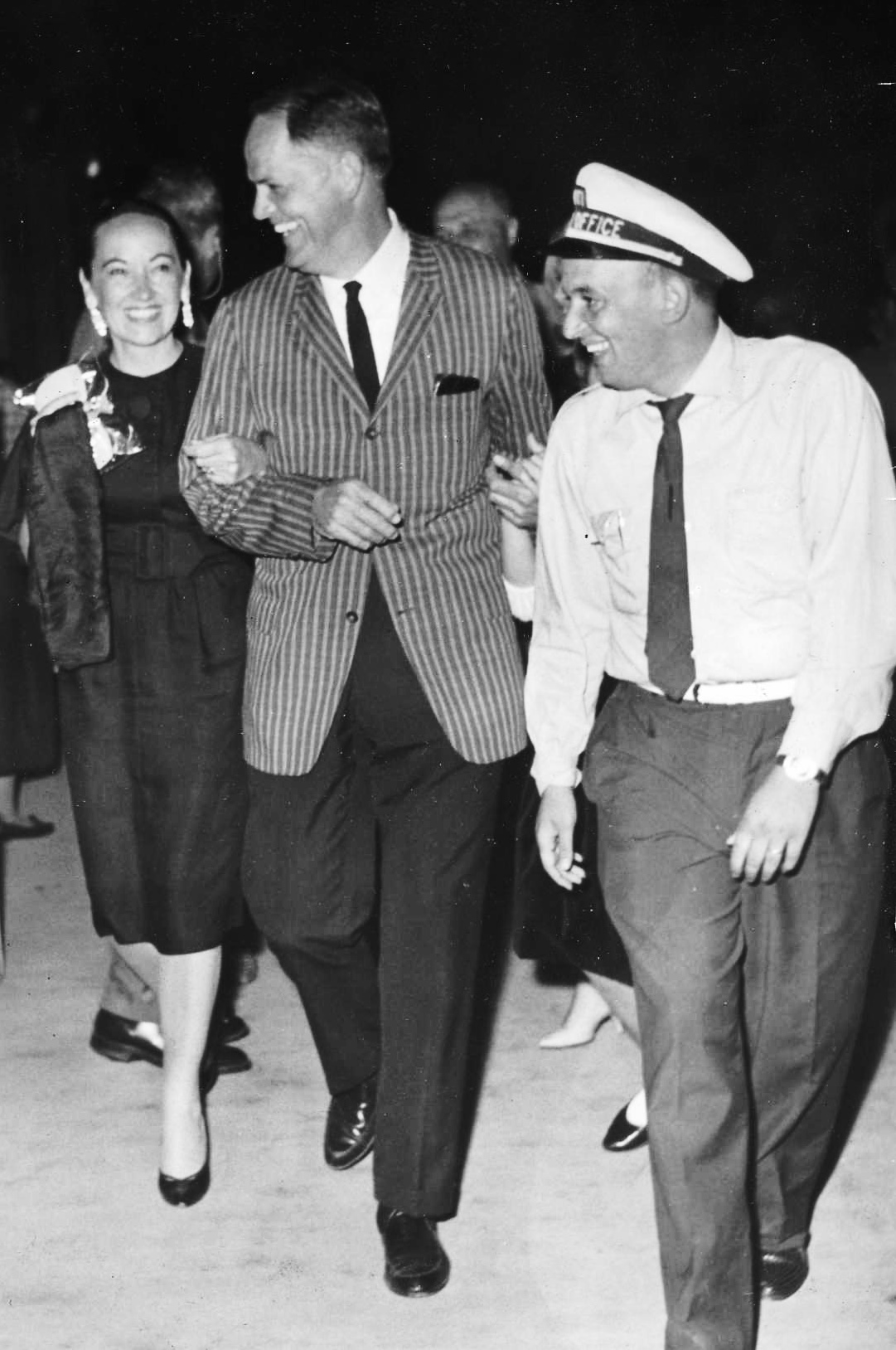

My parents, Naples, Italy, 1961.