During the last decade, David Koch (above) and his brother Charles gave nearly $50 million to a network of policy and political groups that disparage climate science.

This six-part series, "Unreliable Sources: How the News Media Help the Kochs and ExxonMobil Spread Climate Disinformation," documents that the press routinely cites fossil fuel industry-backed climate contrarian think tanks without reporting their funding sources. For part 1, click here; part 2, click here; part 3, click here; part 4, click here; and part 5, click here.

Part 6: It's Time for the Media to Stop Giving Climate Contrarians a Free Ride

In October 2011, a government and industry watchdog group called the Checks and Balances Project sent a letter to the New York Times public editor -- what other papers call an ombudsman -- criticizing the paper for failing to report op-ed contributors' funding sources. Signed by more than 50 journalists and educators, the letter called on the paper to "set the nation's standard by disclosing financial conflicts of interest that their op-ed contributors may have at the time the piece is published."

The letter singled out an op-ed by Manhattan Institute fellow Robert Bryce as a prime example. To try to make the case that natural gas and nuclear power are more advantageous than solar, wind and other renewable technologies, Bryce overstated how much land renewable energy projects would need and ignored his favored energy sources' short-comings. Checks and Balances pointed out that Bryce's author bio failed to mention that two Manhattan Institute funders -- ExxonMobil and the Koch brothers -- are in the natural gas business.

The paper's public editor at the time, Arthur S. Brisbane, responded in an October 29 column, "The Times Gives Them Space, but Who Pays Them?" "...[E]xperts generally have a point of view," Brisbane wrote. "And the Manhattan Institute's dependence on this category of funding [the fossil fuel industry] is slight -- about 2.5 percent of its budget over the past 10 years. But the issue of authorial transparency is an important one, albeit one that isn't always simple."

Brisbane then asked the Times editorial page editor, Andrew Rosenthal, to weigh in--and then gently disagreed with him.

As for Mr. Bryce, Mr. Rosenthal said the Op-Ed article itself made very clear that he was a proponent of traditional energy sources. The Manhattan Institute is "well known for its pro-market stances, including its skepticism of subsidies for alternative energy," he said.

Certainly, the Manhattan Institute is well-known to some, including organized groups like the Checks and Balances Project, whose Web site's promotion of green energy makes clear that it is on the opposite side of the energy debate (something the petition does not mention).

But I don't think every reader knows what the Manhattan Institute is. So, while I recognize that the Times has limited space in print to provide more disclosure, I believe it should do more to help readers learn about outside Op-Ed contributors.

Did the Times take Brisbane's advice? Does it now disclose op-ed writers' financial conflicts of interest? Not that I've noticed. And I don't know of any newspaper that does.

That's a problem, not only when it comes to identifying contributing writers, but even more so when it comes to identifying sources cited in climate and energy news stories. More often than not, top U.S. news organizations fail to inform the public that spokespeople from seemingly independent climate contrarian policy groups are surrogates for the fossil fuel industry -- and that they are deliberately misrepresenting climate science and the potential of renewable energy.

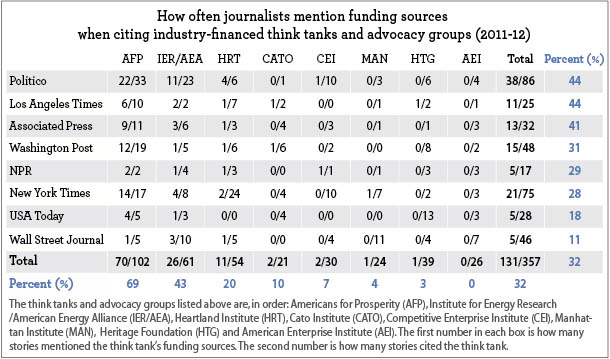

To measure the extent of this oversight, I reviewed two years' worth of climate and energy stories from the Associated Press, the trade journal Politico, NPR, and six leading newspapers -- the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. It turned out that 68 percent of the time, these news organizations neglected to provide information about funding for eight prominent climate contrarian think tanks and advocacy groups I call the Oil Eight. (For my survey results, see the table below, and for more information, click here.)

The Oil Eight includes the American Enterprise Institute, Americans for Prosperity, Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute, Heritage Foundation, Institute for Energy Research (and its political arm, American Energy Alliance), and Robert Bryce's Manhattan Institute. Altogether they received $6.7 million from ExxonMobil and $15.76 million from the three main Koch family foundations between 2001 and 2011. (For more details, see this list of the Oil Eight's primary fossil fuel industry funding.)

Why Don't Journalists Disclose the Industry-Think Tank Connection?

Given that each of the news organizations I tracked mentioned funding sources on at least five occasions between January 2011 and December 2012, they can't claim to be unaware of the connection. So if they could mention fossil fuel industry funding once, twice, even five times, why didn't they mention it more often? I contacted a few reporters to find out.

One reporter echoed Brisbane's observation about limited space. "Just look at how few inches we get in print!" she responded in an email. "If we cite Heritage's funding source, we have to cite your [Union of Concerned Scientists'] funding source, and all of that takes space."

Space is definitely an issue. Reporters need space -- or time when it comes to radio and television -- to tell a complicated story like climate change. And space is harder to come by, at least in newspaper print editions, while broadcast reporters have only a few minutes to cram everything in. But given ExxonMobil and the Koch brothers are now the largest remaining climate contrarian funders, using the descriptor "fossil fuel industry-funded" at the very least to describe a contrarian group wouldn't take up much space or time. And it would signal loud and clear that the group is not impartial.

What about the reporter's contention that organizations like mine are fair game, too? In reality, there is a world of difference between the Oil Eight and the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), as well as most other public interest groups. The Oil Eight are mercenaries. They represent the interests of their corporate funders, which have a clear financial stake in frustrating federal and state efforts to address climate change.

Unlike the Oil Eight, UCS -- which is supported by individuals and foundations -- will not accept corporate financial or in-kind contributions that would create an actual or even an apparent conflict of interest. Likewise, UCS will not accept funding from a company that could gain a competitive advantage or other benefit from our work. (For more information about UCS's funders, click here.)

Most public interest groups have very tight corporate funding restrictions or shun it altogether. So when a public interest group surreptitiously takes corporate money and promotes its financial interests -- which is what the Sierra Club did a few years ago--that revelation is big news because it's an anomaly. Reporters could write that same story about any one of the Oil Eight every day, but it would not be news. That's how they roll. And that's why it is critical for reporters to make their financial links explicit.

Another reporter picked up on one of Brisbane's other points. "We should make clear that the organization is not neutral; we should label it 'conservative' or 'libertarian,' for example," she said. "But if ExxonMobil or the oil industry is not the majority funder of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, it's too much detail for that level of passing reference."

Implicit in that view is the contention that if funders are not responsible for a significant portion of a multi-issue think tank's annual budget, they don't have much influence. In fact, they have a lot -- at least over the specific programs they underwrite. Just ask David Koch. He'll tell you that he and his brother Charles keep their grantees on a short leash. "If we're going to give a lot of money, we'll make darn sure they spend it in a way that goes along with our intent," Koch told Brian Doherty, an editor at Reason magazine. "And if they make a wrong turn and start doing things we don't agree with, we withdraw funding."

Meanwhile, the reporter's solution of labeling contrarian groups "conservative" or "libertarian" doesn't go far enough to explain whose interests they're serving -- and labels can be deceiving. For example, most if not all of the Oil Eight call themselves "free-market" policy groups. Last December, five of the Oil Eight -- the American Energy Alliance, Americans for Prosperity, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute and the Heritage Foundation's political arm, Heritage Action--held a press conference to urge Congress to kill a wind industry subsidy that was due to expire at the end of the year. In keeping with their free-market philosophy, they denounced the wind production tax credit as a "wasteful handout." At the same time, however, the five groups -- which, as I've pointed out repeatedly, receive fossil fuel industry funding -- maintain that eliminating subsidies for oil and gas companies would be "a massive tax hike on a vital sector of American industry." That hardly qualifies as a consistent free-market position.

Contrarians are Wrong on the Science & Wrong on the Policy

New York Times blogger Andrew C. Revkin, who left his full-time job as a Times environment reporter in 2009, addressed the issue of identifying think tank funders in a chapter he wrote for a 2007 book, Climate Change: What it Means for Us, Our Children, and Our Grandchildren. He published an excerpt in his Dot Earth blog in October 2010:

One practice that can improve coverage of climate and similar issues is what I call ''truth in labeling.'' Reporters should discern and describe the motivations of the people cited in a story. If a meteor-ologist is also a senior fellow at the [George C.] Marshall Institute, an industry-funded think tank that opposes many environmental regulations, then the journalist's responsibility is to know that connection and to mention it.

Revkin elaborated in a recent email. "If a story is about climate science, [reporters should] talk to climate scientists (or other researchers whose expertise is relevant, as with statistics)," he wrote. "If story is about policy -- the role of taxes, regulations or other approaches -- the door is open to the full cross section of society, including libertarians and companies."

I obviously agree with Revkin's first point. When writing about climate science, reporters definitely should be talking to climate scientists -- not the relative handful of scientists who are paid by the American Petroleum Institute, ExxonMobil or the Kochs to malign their work. Reporters also need to be wary of other scientists who may be prominent in their own fields but have a tenuous grasp on the topic.

But what if the story is about policy? Revkin says "the full cross section of society" should be included in the discussion. OK. But the principal reason contrarian think tanks refute climate science is because their benefactors -- the fossil fuel industry -- would take a major hit if the U.S. government actually came up with policies to address it in a serious way. That's why it's so important for journalists to identify fossil fuel industry-backed spokespeople as such not only in climate science stories, but in policy stories as well. Anything less enables the industry to launder disinformation through its climate contrarian network.

Is it Time to Pull the Plug on the Climate Contrarians?

So what can journalists do to better protect the public interest?

First they need to understand the climate contrarian con game, and then they need to explain it to their readers, listeners and viewers. The Oil Eight -- and dozens of other contrarian think tanks -- are shilling for an industry that will do whatever it can to maintain its excessive profits and its stranglehold over our political system.

Every time journalists cite contrarian scientists or industry-funded think tank spokespeople, they validate them as a trustworthy source. And every time journalists fail to disclose where contrarians get their funding, they fail to explain whose interests they serve.

Despite the limitations of newsgathering, journalists have the responsibility to point out when funding sources may bias a source. They also have the responsibility to provide the facts when their sources distort them. When journalists abdicate that obligation and become mere stenographers, they corrupt the public debate.

All of what I just said, however, presupposes that the news media will continue to quote climate contrarian think tank "scholars"--and publish their opinion pieces--regardless of the fact that they have been trying to hoodwink the public for years about the reality of climate change and the pressing need to address it.

The other option, of course, is to stop quoting climate contrarians altogether. Do they really deserve a seat at the table? Are they really qualified to comment on this issue? After years of giving contrarians a free ride, perhaps it's time journalists left them out of their stories. These unreliable sources have caused enough damage, and we can't afford to waste any more time. #

Elliott Negin, the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is a former NPR news editor and former managing editor of American Journalism Review.