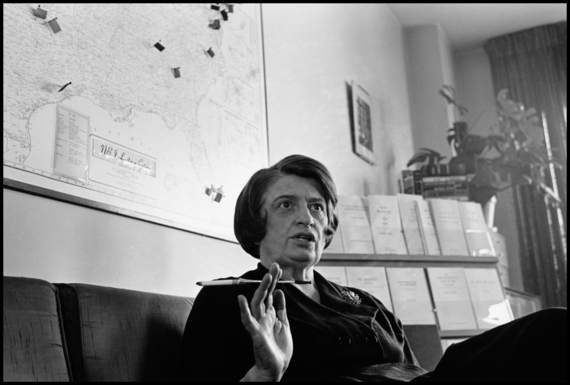

Ayn Rand -- the name makes liberals gasp and libertarians puff up their chests. But her philosophies aren't actually that polarizing.

After reading Rand's most famous work, Atlas Shrugged, I find my thoughts on politics and life profoundly inspired. Her characters and philosophical convictions are unapologetically pragmatic and simply refreshing.

Rand's work reminds me of an important lesson: haters will hate.

As a woman in 1957, Rand had the gumption to reframe overly politicized topics, like charity and love, which she thought threatened to obscure the value of the American dream.

Her philosophy or Objectivism might seem crass on first impression, but only because the integrity of her thinking made her unconcerned with political correctness. Or, as she would say, "if one's actions are honest, one does not need the predated confidence of others, only their rational perception."

In essence, Rand's philosophy is "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity and reason as his absolute." In other words, the philosophy calls for one to follow reason above whim, consistently recognize reality, pursue one's own happiness before that of others and be productive.

Rand used these unpretentious tenets to challenge a number of axioms -- and the legacy is liberating.

I am fabulous

Perhaps most obvious in Rand's writing is a call to unleash barefaced confidence. Her characters are shamelessly proud of their abilities, yet Rand manages to paint them without a hint of conceit.

Dagny Taggart, the protagonist of Atlas Shrugged, is a female railway executive operating a transcontinental line in a man's world who is buttressed by pride and even pleasure in her own capability.

For example, as Taggart faces near death she feels "in a flash of its full, violent purity, that special sense of existence which has always been hers. In a moment's consecration to her love -- to her rebellious denial of disaster, to her love of life and of the matchless value that was herself -- she felt the fiercely proud certainty that she would survive."

Rand's endorsement of such unashamed self-esteem makes it clear that women, especially, should stop confining their ability and self-worth.

I am not my sister's keeper

Secondly, Rand argues that we are not responsible for the lives of others -- not intending for people to never do good for one another, but only as a trade of virtue.

For example, in Atlas Shrugged, Hank Rearden, a brilliant steel industrialist, will not give his brother a job in his mills. Rearden's family condemns him, but he is steadfast in his decision because his brother has no relevant skills and is not interested in learning them. However, Rearden is eager to provide another young man, who isn't afraid of hard work and is excited about developing his own ability, with an opportunity.

Because Objectivism makes one's own happiness the central concern, it frees us from carrying the burden of supporting those who tirelessly ask for more. It doesn't mean, however, that providing a worthy candidate with an opportunity could not enhance our own happiness.

In a world where individual rights seem to be on the rise without an apparent corresponding escalation of individual duties, Rand's perspective is energizing.

My love is not sacrificial

Moreover, Rand frees us from the perspective that love is necessarily sacrificial, arguing that love is rather recognition of equal greatness between two people, or "our response to our highest values."

The argument remains controversial and relevant. If nothing else, it reminds us that love should uplift, fostering our potential greatness and bearing witness to our deepest values.

After all, when love holds us back and forces us to live a life in which we don't believe, shouldn't we let it go?

And so on

Rand goes on to confront other adages based on the principles of Objectivism. And, like most theories, Objectivism does include extremes, like the failure to recognize any form of spirituality or the failure to support any state responsibilities beyond the minimalist requirements of laissez faire economics.

However, one shouldn't write off Rand's work. Like any good writer, her audacious statements grab the reader's attention, while her analysis is actually much less extreme and appeals through carefully constructed logic.

Rand isn't a diplomat -- one writer refers to her as the "rebel queen of the icy kingdom, vilifying empathy and solidarity." But I respect her resolution in drawing confident conclusions and the value of the conclusions themselves. In an age where life has become apologetic and entitled, Atlas Shrugged is a truly revitalizing, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps saga.

Many will see my Rand-inspired outlooks as insensitive, but I feel liberated by and proud of my renewed thinking. Her work reminds me to have the integrity to reach my own conclusions through reason and to act on those beliefs without being wary of convention.

After all, haters will hate.