This is the fourth of a series of interviews that focus on Local 829's Scenic Artists' "behind the scenes" talent who sculpt and paint in a variety of ways the sets we see on television, in movies and documentaries, on theater stages, and in the backgrounds of television and internet commercials.

I first met Bradley Rubenstein very early on in my days in the scenic arts, and it was immediately apparent that he was, and still is, as respectfully dedicated to his work as a fine artist. I've followed his career closely since then, watching his art delve deeper and deeper into the human condition as he distorts and mutates his subjects. Most recently, Rubenstein will have one of his warped and mangled human forms in an exhibition titled HEAD that I curated for the Hampden Gallery at UMASS Amherst.

The interview below begins just days before the installation of HEAD, and is followed by a few thoughts and comments after my return from the opening. The goal of my interview is the get to the essence of Rubenstein's seemingly endless quest to analyze, interpret and re-present reality.

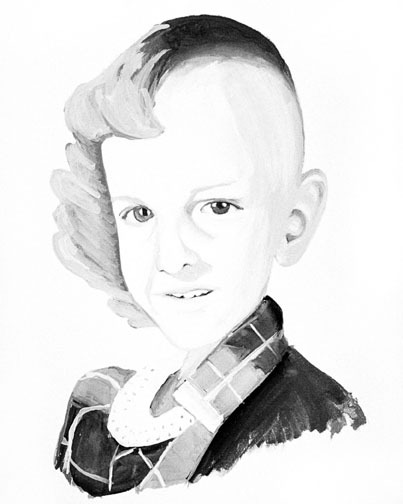

Bradley Rubenstein, Untitled (1995), ink on paper, 36" X 24"

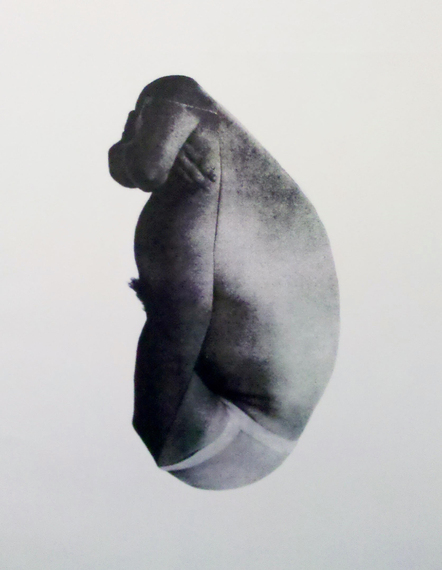

DDL: Let's start with the piece you have in the HEAD exhibition. When discussing the headless figure in your drawing, I write in my essay: "Are we looking at the future - a mutation set up for a specific task, or a mental eunuch poised and prepared for some invisible or imagined foe? Either way, we are left with a haunting form, a freak borne of science not nature reminding us that processes in physiology have their own system of checks and balances, and those rules, when set awry, have little to do with our own preconceptions."

Am I close to your thinking there?

BR: I like the poetry of that description. There is something kind of gothic about it that is very H.G. Wells. I think that it is really the present I was looking at, though, when I was doing those drawings. I had been looking at different ways of painting the figure, which is really what interests me, but I wasn't interested in approaching it like Freud or Pearlstein, which seemed like a dead end. I liked Kiki Smith's sculptures, the way that she combined a psychology of the body with a scientific, analytical approach. She was an EMT, and the idea of trauma seemed integral to her work. In some of the work I was doing at that time, like the kids with the puppy-dog eyes, I tried to get at that idea of something real, like eye transplants being done at UCLA with animal eyes, and examine it through art--portraits of kids with animals. Only in this case the kids and animals were the same portrait. With the drawings, like the one in your show, I was interested in doing figure studies that referenced the symbiotic systems that comprise the human body. At the time I think it was believed that there were five systems--like the spinal cortex, the gastrointestinal system, etc.--that all operated somewhat independently. So, how do you do a drawing of the figure when the figure isn't just one entity? It was my Cubist Period, I guess.

DDL: I see. It's always fascinating how stuff that is relatively concrete or scientific is represented after it's filtered through an artist's brain. I think that's why I'm still drawn to the Surrealists. It was the way they interpreted the advancements in everything from biology to physics that keeps the work fresh, in my mind at least. Thinking about the kids with the puppy-dog eyes and the images of children who have their faces divided in half and re-presented as two humans in one: is this as much about a surrealist approach as it is a Cubist leaning? Most might say conceptual, a far more overused and misleadingly term.

BR: I'm not sure there was that much of a distinction between what Picasso was doing with his later Cubism and what Dalí was doing with his Paranoiac-Critical method. It was a particularly interesting time where you have Marie Curie's x-rays and Sigmund Freud's analysis--both ways of trying to see what is going on inside a living human body, and I say living as opposed to, say, da Vinci, who was investigating anatomy 400 years earlier on corpses. Now, both Picasso and Dalí liked to make comparisons between what they were doing and what was happening in science. Picasso liked the Wright Brothers, and Dalí wanted Freud to look at his paintings, but, really, they were just creatively misunderstanding these other disciplines. That, actually, is something I think is at the heart of what I do, and something I like to see in art. Creative misunderstanding. You start with something that might be pretty concrete, and then you interpret it rather than transcribe it. I'm not a genetic engineer. Not a psychiatrist. I just glean from what is going on in the world and make pictures. I think maybe it might be called the surrealism of everyday life. Like, I read a sentence in the newspaper the other day, "Caitlyn Jenner was 20 years old when she won her first Olympic Gold Medal in the Men's 100 meter dash." Now, how great is that, right? People complain the Wi-Fi sucks on airplane flights--or the movie. These are things that people take for granted now but were the stuff of imagination until very recently. The boy/girl hybrid heads, for instance...most people did not really get them at the time, but that was more than 20 years ago. I think in the best case, reality catches up with art.

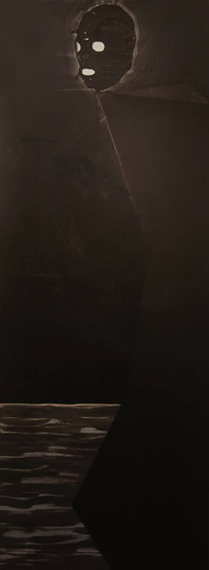

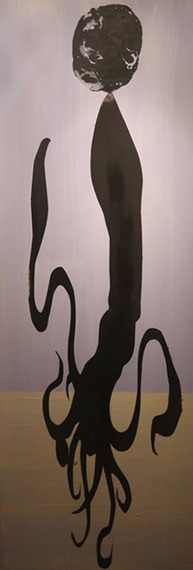

DDL: I like that, "reality catches up with art." And it is true--an artist's creative process most often advances in many different ways without ever addressing or conforming to any particular formula or type, so the "surrealism of everyday life" makes perfect sense for your approach and thinking. Let's talk about the more recent paintings on doors. These works feature, for lack of a better term, a "perched" head atop a mesmerizing and gesturing mass or form that often has a palpable iconic presence¬. It is almost as if they're a logo or symbol for some sort of ages-old secret society or belief system. Perhaps a "science fiction of everyday life"?

BR: Yeah, that's a really good read on them. They are portraits of a sort, but in an iconic way, like a Kouros statue or a Giacometti portrait. I was really taken by de Kooning's Women paintings on doors from the late 60s. The way that he captured these imaginary figures on a beach--he gave them a palpable sense of reality, of movement, narrative, or whatnot, and grounded them in a space--a door--which is real. My friend Brenda Goodman uses doors, and I was talking to her about why she does. The reasons were very similar. Also, there is a nod to Renaissance panel paintings, with them being on wood instead of canvas. There is a lot going on in them, but I am trying to create a painting that has few moving parts--something streamlined so that the viewer apprehends everything all at once and can then take it apart and see the movement...the story.

Cormac McCarthy said that he is only interested in writing that deals with death. That really strikes me as a concise way of describing how I feel about painting. It should tackle serious material; it should be iconic, address the eternal. The paintings are portraits of people who are interesting to me. When I don't have a subject, then I do self-portraits. I did a recent show with Mira Schor, a painter who has been my friend for 20 years and whose work has also been of great influence to me. We called the show Imaginary Anatomies. I think that is a good description of what I paint.

I start with the portrait, the idea of a figure painting, and try to get at the psychology of the figure. I begin with the head, with an objective element, like a sketch or a photograph, then build the narrative through the gesture of the figure. The blacks of the pigments tell the story. The paints are hand ground--carbon, for instance, for the head; we are carbon-based life forms. Different elements for different elements in the painting. For instance bone black for the spinal elements--those are the flat planes. They are based on needling points in acupuncture--meridians, or chakras. In the painting Night (2013), the figure is part goat. I was looking at Picasso's later works, the ones where he really tackled aging, and saw the dark humor there. The goat. The bull. The minotaur. The rest of the figure in that painting is like a map; it is the needling points of the male urogenital system--dangerous needling points that are seldom used. They are stretched out like Buckminster Fuller's geodesic maps, or a Mercator projection, to create the planes. The geometry gives the figure a sense of stasis, of arrested movement, of stillness. Then, growing out of the sides of the figure are three anamorphic skulls. They mark the spots of greatest danger, the places to not put the needles. The figure is either holding them or they are stuck into it like a picador spears into a bull. There's your narrative, a meditation on mortality.

In the portraits I try to find an equivalent, something about the person. I like the marine elements, for example, of squids and octopuses. The squids obviously have the ink as well as the carbon. The figure of my niece on the beach is a good example. How do you capture something like that? Playing on a beach, this tiny figure engulfed by the giant ocean? Again, de Kooning got it in Clamdigger (1976). I think I got something of that--the iconic, a moment captured.

And there is something of that in making a film, which I'm drawn to. People see a movie, and they are immersed into a story; there is atmosphere. This also happens with television, but that is more of a writer's universe. When you make a film, in some ways, whether intentional or not, you are making a documentary, recording fact. You have all of these different elements, the actor, the camera operator, the make-up and hair department, the scenic painter, the set decorator, the prop person. They all assemble at a very specific time and place. For a few minutes, or sometimes hours, their work all hinges on the actor reading specific words. All of this is captured on film--all of this plus the incidental elements, such as the movement in the background. Things that just happen and are left in the film. Then all of these moments are cut together to tell a story. The story is the fiction, but the film is the fact. All of these people were here for a moment and did things, and it is all here, on film--what Bacon called the brutality of fact. I like that as a description of both painting and filmmaking.

Post HEAD opening:

A few days after the Head exhibition opening, I have the luxury of time to reflect on when the curatorial process begins. It is best to have something of a broad-spectrum of parameters with regard to the theme because, as with life, there are many different roads one might take. HEAD began over three years ago with an exhibition I co-curated with Robert Curcio for Bosi Contemporary. The show then was as eclectic and fun to curate as the current version of HEAD is now and I am very grateful to Anne LaPrade Seuthe and Sally Curcio for this opportunity to have a second installation of HEAD at the Hampden Gallery.

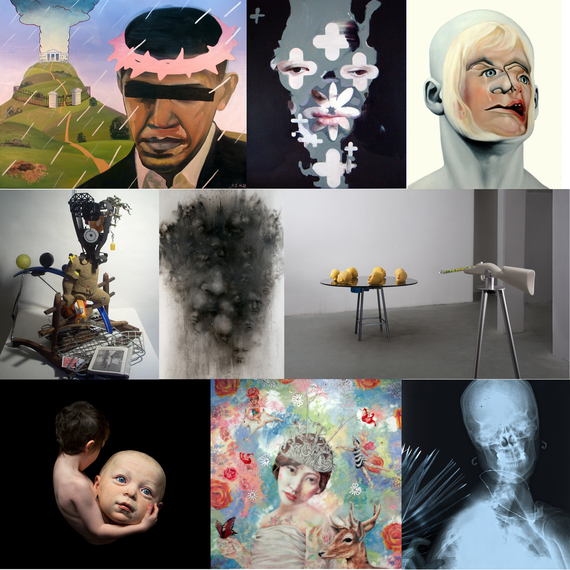

A selection of works from the first HEAD exhibition at Bosi Contemorary, top row left to right: Ronald L. Hall's Blind Nation, Richard Butler's smallconfessional and Christopher Avella-Bagur's Face FS Still Child 2; second row left to right: D. Dominick Lombardi's Urchin #48, Rieko Fujinami's Black Rain and Esther Naor's Be a Good Girl; third row left to right: Nina Levy's Boy with Baby Head, Lori Field's Be-Careful and Benedetta Bonichi's Donna Con Ventaglio

Looking back at Michiko Tachibana observations just before she interviewed Robert and me for her article in NY ART BEAT back in the summer of 2013 I was pleasantly surprised as I read again, her thoughts: "Upon a quick viewing of a section of the works on display, some of the terms that crossed my mind were: the imprisonment of perspective, the symbolic relationship between frailty and vanity, self-disgust arising from the internalization of external and wholly subjective standards, childhood bliss stemming from ignorance."

In his review of the show, John Mendelsohn wrote: "Curators D. Dominick Lombardi and Robert Curcio have gathered 36 idiosyncratic examples of the head as social signifier, troubled mask, and dream-like presence. The eleven artists represented here unsettle us with their evocations of head as the repository of the psyche which demands to make itself known."

It's responses like the above and the feedback from the viewing public that help drive the artists and the arts. Thinking and speculating about any artist's intent is as important as the artist's own actual objective - and that's why artists need to show and their art needs to be seen and sometimes that works best in a group exhibition. In a group show you have a chance to see many different voices reflecting upon one rather basic premise whether that is something that the artist is conscious of at the time of the making of the art, or something that a curator sees and interprets later on. I guess what I am trying to say is the greatest reward in curating a group exhibition is that multifaceted connection between the artists and the public.

On top of all this, when such a variety of art is taken to someplace new, someplace far from where it was created, and in this instance thoroughly complemented by art that is more regional or local to Western Massachusetts and Amherst itself, something else happens - the conversation, the content and the meaning expands. This happens because the artists bring their insights, observations and energy to a new place and context. And finally, at the opening everything comes together for one very big day - the first day the public sees the exhibition where reactions are expressed and new thoughts and insights begin to unfold.

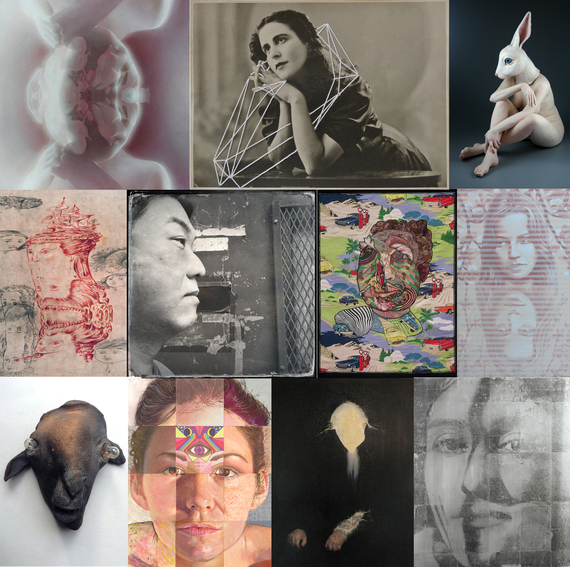

A selection of works from the current HEAD exhibition at Hampden Gallery, top row left to right: Yoshkazu Yanagi's Child of Space (maroon), Rossana Taormina's Portrait 2 and Cynthia Consentino's Nude; second row left to right: Brian Fekete's Encyclopedic Series No 5, Roman Turovsky's Kim, China Marks' Drive He said and Ivan Pazlamatchev DQ; third row left to right: Susan Halls Goat Head (bulb eyes), Outside-The-Line-Collective Mandy, Moray Hillary An Act of Performance and Eileen Claveloux Diasporan Portrait 2: Shahan

If I have enticed any of you to see the exhibition, and you are thinking of combining it with a one or two night stay during New England's most glorious time of fall foliage viewing then I have a few recommendations for you. The Amherst Inn, where Diane and I stayed, is a pretty special place - great décor, wonderful people running it and it's just a short walk to N Pleasant Street where you will find two excellent restaurants that we just happened to try.

For the restaurants, I'd like to pass my keyboard to Diane for her commentary, as she is a published reviewer.

We went to Miss Saigon on our first night, a very busy favorite of the locals and neighboring university students and faculty is affordable comfort food - especially for a cold fall evening. We enjoyed sharing an appetizer of spring rolls: one vegetarian, tofu wrapped in rice paper with fresh avocado, mint, carrot, cucumber, lettuce and rice vermicelli. In the second we added pork served with two dipping sauces - one hoisin style and the other a clear lightly spiced sweet vinegar based dip. Tired and hungry, we wanted the reinforcement of a good cup of soup and a satisfying noodle dish. First the banh canh, a thick noodle beef soup topped with crisp mung bean sprouts and other vegetables, topped with fresh herb seasonings. The second noodle dish was similar to traditional pad thai- nicely prepared and not overly sweet.

Our second evening was spent at Metacomet Café, a place where we enjoyed for different reasons. Yes, it is fairly priced but far less busy and more relaxed than Miss Saigon. Featuring a simple menu that largely consists of ground 100% grass fed beef burgers, lamb burgers and a veggie burger with your choice of toppings it's easy to decide what to try. Dom chose a lamb burger with chic pea fries and to change it up a bit, instead of ordering another burger, I ordered the Swedish meatballs served with a dollop of homemade mashed potatoes, some local lingonberry jam and thin slices of kirby cucumber - two excellent choices for the hungry and restless to stop and savor local fare.

Both restaurants are BYOB, but that is just fine as there is Russell's Liquor Inc. on Main right before light at N Pleasant. They have a full selection of beers, especially some of the IPAs such as Stone IPA that has a very short shelf life and is incredibly fresh and pleasingly bitter-hoppy.