Corporate boardrooms are not known to be reliable benefactors of populations in greatest need. And yet, many of the nation's most recognizable corporations -- the Wells Fargo Foundation, the Bank of America Charitable Foundation, the JPMorgan Chase Foundation, ExxonMobil Foundation, the Walmart Foundation and others -- have ratcheted up their giving to underserved communities in the last decade, some by as much as 40 percent.

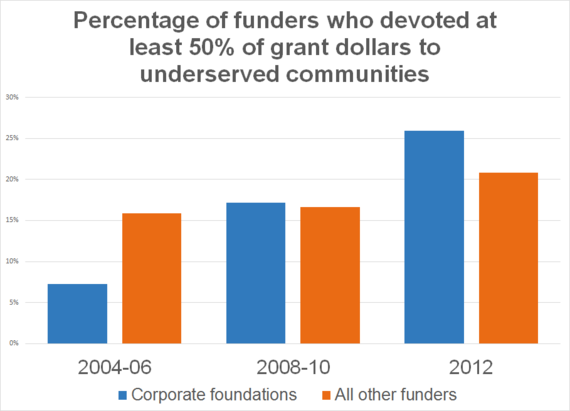

According to the latest available data, grantmaking by corporate foundations to underserved communities -- racial and ethnic minorities, the poor, women and girls, LGBTQ people, people living with AIDS and others -- increased dramatically from 2004 to 2012. Corporate funders now outspend their independent, family and community foundation counterparts in giving to these important populations. Between 2004 and 2012, the average amount given by corporate funders to underserved communities more than doubled, while the average amount given by non-corporate funders increased by about 50 percent. Additionally, 48 percent of corporate foundations' grant dollars went toward underserved communities, compared to just 38 percent from all other foundations. And three times as many corporate foundations allocated at least 50 percent of their annual giving to such grants in 2012 compared to 2004. This is a threshold that may be used to identify those grantmakers most committed to serving the public good.

Let's be honest: for most Fortune 500 companies, philanthropy is a vehicle for corporate interests. Corporations are designed for profit maximization and market expansion, and corporate philanthropy generally is in service to those objectives. When describing their goals, surveyed corporate philanthropists themselves admit that their aim is to expand into new markets, improve employee recruitment and retention, manage risk and enhance company reputation.

Less explicitly discussed, but equally important, are the ways in which many corporations use philanthropy to further political goals. Sometimes, they give to charities that benefit particular constituencies in an effort to win favor from those groups and the elected officials who represent them. Telecom industry contributions to civil rights groups may have helped sway them into siding with the industry on net neutrality. Other times, corporations fund a variety of noble causes to help convince regulators and lawmakers that they are benevolent and have the best interests of the community at heart. The banking industry often turns to philanthropy to stave off unwelcome regulation or divert attention away from egregious practices.

Wells Fargo President and CEO John Stumpf said in 2008, "When we build in ethnic communities, we build ethnic stores. Might we have gotten that concept without our community outreach? Maybe. But we wouldn't have gotten there as fast." The same year, trouble in the housing and credit markets cascaded into a global recession. Wells Fargo has since been fighting lawsuit after lawsuit alleging unfair lending practices targeting communities of color in the lead-up to the crash, and many of the suits have ended with settlements. When a suit brought by the city of Memphis was dismissed, Wells Fargo highlighted its foundation's work in Black and Latino communities in a press release about the case - a rhetorical shield for the bank against a volley of accusations alleging misinformation and outright theft.

Regardless of how one feels about their motives, it's clear that corporate funders have, through enlightened self-interest, made a shift towards prioritizing the underserved. While undoubtedly a change for the better, this is part of a larger, more complicated story. How can philanthropy, progressive movements and civil society reconcile the motives of corporate philanthropy with their own? This isn't an academic question: corporate foundations are playing an increasingly large role in providing much-needed funding to nonprofits serving the poor, people of color and other marginalized groups. Those serious about organizing and empowering these groups around human and civil rights, affordable housing and other critical issues ought to be suspicious of the rise of corporate philanthropy, especially given how market practices and outcomes are intertwined with these issues.

More urgent, however, is the need for non-corporate funders to start prioritizing marginalized groups the way corporate foundations do. If major philanthropies aren't giving to benefit the poor, communities of color and other underserved groups, but corporate funders are, it begs the question of what impedes them from doing so.

Donors are influenced by a variety motivations, and that's part of the beauty of the pluralism of American philanthropy. But I believe that most donors share a desire to make a positive difference for as many people as possible and for their giving to have a positive impact on the world. However, not all philanthropic strategies are equally effective. Where the money goes and how it's given away matters.

Every issue that our society faces -- whether it's related to health, education, clean air and water, the arts, etc. -- benefits when foundations prioritize the needs and empowerment of underserved populations. By directly confronting the social and economic disparities these communities face, foundations can encourage positive outcomes that ripple through all of society.

This kind of smart giving is strategic, socially just and has a staggering potential for transformative impact. There are many foundations around the country that are already giving in this way. The New York Foundation funded a group that increases tenant participation in determining annual rent increases for rent-stabilized apartments. Toledo, Ohio's Needmor Fund supported an organization that increased voter turnout in the 2014 elections by engaging disenfranchised voters in Kansas and Missouri. D.C.'s Hill-Snowdon Foundation is showing leadership in the BlackLivesMatter movement.

Imagine what we can accomplish if at least 50 percent of the $50 billion in annual foundation grants is channeled into this kind of high-impact giving.

Corporate interests are changing philanthropy. More money is getting to those most in need, but corporate funders are also using philanthropy to repair their public image and meet corporate and political objectives.

I urge the nation's independent and family foundations to take stock of their own giving and boost their support for women and girls, communities of color and other underserved populations. Doing so will most certainly help bring about a better society and a better world.

Aaron Dorfman is executive director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter.