The odds were stacked against Gircilene Gilca de Castro when she set out to launch her catering company several years ago.

Gilca de Castro, 44, comes from a self-described “very humble” background. Many women in her community in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, have several kids and few job skills by the time they reach their late teens, she said. Gilca de Castro had already launched a company that failed after just one year.

Today, her business has 12 clients and a staff of 45, most of whom are women. The catering company allows Gilca de Castro to afford a prestigious bilingual school for her 7-year-old daughter, she said recently, her damp eyes beaming with pride. “My brothers were always like, ‘You’re crazy, how are you going to start a company now?’” she said through a translator. “That’s where the character, the profile of the entrepreneur, comes out. You believe in yourself.”

In addition to her own perseverance, Gilca de Castro credits another, more surprising source for her success: Goldman Sachs. Gilca de Castro is one of the thousands of graduates of Goldman’s 10,000 women initiative, which aims to help female entrepreneurs in emerging economies grow their businesses. Through the selective program, women attend classes at local business schools and participate in networking and mentoring events, with an eye towards learning skills like writing a business plan and raising capital.

Goldman launched the program in 2008, when the financial sector had become the public’s punching bag. Goldman, later dubbed the "Vampire Squid," symbolized for many the kinds of excesses, greed and penchant for extreme risk that dragged the economy into crisis. But for Gilca de Castro and thousands of other women in the program around the world, the bank has offered new resources to help them grow their small businesses.

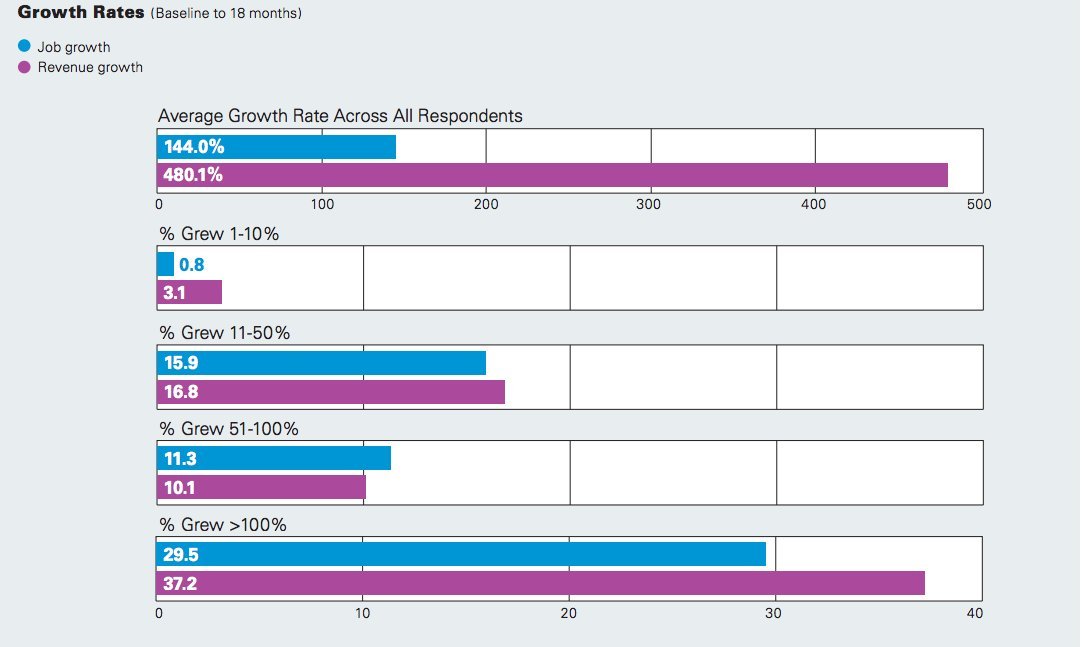

Nearly 70 percent of the participants in Goldman's program increased their revenues 18 months after graduation, according to a progress report by researchers at Babson College, produced earlier this month in collaboration with the bank. The women saw revenue growth of 480 percent on average, the report found.

This chart from the Babson report shows how program participants have increased their staff and revenues after 18 months.

Despite the impressive growth, the program has had trouble moving the needle in one important category: Convincing the entrepreneurs to ask for outside money. Just 47 percent of the women in the program applied for external funding before or after completion, even though a large share said they needed it, according to the progress report.

Part of the reason the women are so hesitant to ask for the money is because they’re nervous they won’t get it, according to Patricia Greene, a professor of entrepreneurship at Babson who worked on the report. Even in the U.S., where the business world is theoretically egalitarian, companies with female CEOs made up less than 3 percent of the businesses that got venture capital funding between 2011 and 2013, according to another study published Tuesday by Babson.

“No one likes to fail,” Greene said. “You like to have some confidence that when you’re stepping into something, there’s some good likelihood of success.”

Participating in Goldman’s program helped Sharmila Jain gain that confidence, she said. Jain owns a packaging company in Hyderabad, India, and she was seeking a loan to build a new plant at the same time that she was taking classes at a local business school through 10,000 Women. Securing the funding was of tantamount importance: At the time, Jain was pursuing a large, European client who would only sign on with her if she moved out of her “ramshackle” factory, she said.

As she was contemplating giving up on the client, Jain, 46, shared her story with a professor who urged her to press on. A month later, she got the client, and several months after that she had a brand new plant. Jain now has 57 workers and does $75,000 in business every year, she said.

Jain credits her success both to the Goldman program and to her own "stubborn" attitude in the face of societal pressures to focus on taking care of family instead of on a career. “I thought just because I’m a girl, it doesn’t mean that I don’t deserve respect,” she said.

Success stories like Jain’s are important to more than just the entrepreneurs themselves because “growth begets growth,” Greene said. “It changes stereotypes, changes the amount of money circulating in the economy, creates jobs,” she said.

Some have suggested that Goldman’s program could do more for economic development by not limiting the enrollees to women. At a lunch announcing the progress report to a group that included bankers, academics and philanthropists, a few attendees noted that entrepreneurs in emerging markets all face huge barriers to growing their businesses, regardless of gender. “Most of the efforts these days are more integrated,” said Mauro Guillen, the author of Women Entrepreneurs, Inspiring Stories from Emerging Economies and Developing Countries and a professor of international management at Penn's Wharton School of Business.

And even as Goldman pays special attention to female small business owners abroad, the bank -- like the rest of Wall Street -- could do more to help women internally. Just one of the company's executive officers is a woman, according to Goldman's website, and only about 20 percent of the managing directors in its latest class are female, according to an analysis by CNBC.

Still, since the 1970s, economists have recognized the importance of investing in women to spur growth in countries racing to become so-called “developed markets.” A book published around that time by Danish economist Ester Boserup, called Women’s Role In Economic Development, pushed organizations like the United Nations and the World Bank to launch programs focused on the issue.

“If you have this human capital embedded in women and if for whatever reason they’re underrepresented in any sphere of economic activity, then that’s a wasted resource, you’re wasting at least half of the talent pool,” said Guillen. “It’s impossible for any country in the world to be rich without having a very high labor participation rate by women.”