Key Republican senators were busy on Sunday, expressing their reservations about the latest effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which Senate GOP leaders are vowing to bring to a vote this week.

Taken together, Sunday’s statements make it difficult to see how the bill could pass, although at this point nobody takes anything for granted.

Senate Republicans face a hard deadline of Sept. 30. After that, they lose the ability to pass repeal with just 50 votes, with Vice President Mike Pence breaking a tie, rather than the 60 it would take to overcome a filibuster. Republicans have only 52 seats in the Senate, meaning they can only lose two votes.

At the moment, at least five Republican senators are opposed to the bill or say they are leaning in that direction ― and these are not reasons the bill’s sponsors, Sens. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), can address easily.

Most of the wavering or opposed senators are angry about the rushed, partisan process that produced the bill. No committee of jurisdiction held a hearing on the bill and the Congressional Budget Office will not have time to provide a full analysis, including all-important projections on insurance coverage and premiums, before the Sept. 30 deadline passes.

In addition, and more important, some of the dissenters worry the law will undermine coverage for too many people. Others are insisting upon more dramatic cutbacks in spending and regulation, which would inevitably undermine coverage for even more people. Any effort to please one group is bound to alienate the other even more.

This should not be surprising. Republicans have spent seven years promising that they had a way to repeal “Obamacare,” while giving everybody coverage that would be more comprehensive and more affordable. But these promises are not compatible, at least given the menu of options Republicans are willing to consider.

The Affordable Care Act has its problems, and plenty of people feel worse off, but it’s also brought the number of Americans without insurance to a historic low, improving access to care and financial security. Scale back the law’s spending and regulation, or get rid of it entirely, and the inevitable result will be more people struggling to find care or facing hardship because of medical expenses.

Consider how the Graham-Cassidy bill would work if it became law. It would replace the Affordable Care Act with a less generous program that states would operate more or less on their own, with freedom to waive regulations that protect people with pre-existing conditions. The bill would also cut Medicaid funding on top of that, effectively limiting the federal government’s historic commitment to the program.

Graham and Cassidy insist states can “innovate,” in order to make coverage more available even with fewer funds ― and that the waivers from the Affordable Care Act’s insurance regulations wouldn’t undermine protections for people with pre-existing condition. Neither claim is credible, as a parade of independent experts and organizations have said.

Something like 21 million more people would end up without insurance coverage, according to the latest and most reliable estimate, while some people with cancer, diabetes, and a host of other medical problems would have no way to get the comprehensive coverage they need.

The bill is highly unpopular and has provoked condemnation from virtually every major organization that represents either the people who provide health care, the people who pay for it, or the people who get it. Over the weekend, six groups, including the American Medical Association and America’s Health Insurance Plans, issued a rare joint letter condemning the proposal.

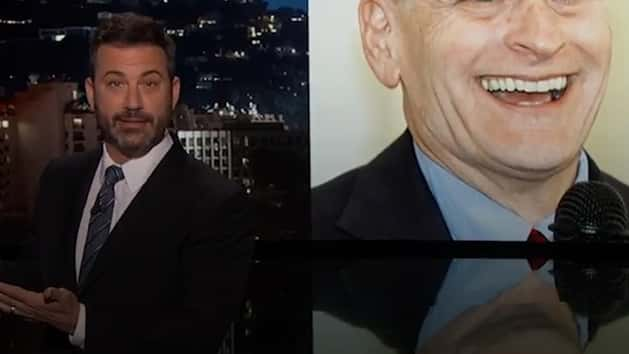

And that’s on top of the hammering Cassidy, in particular, has taken from late night television host Jimmy Kimmel.

Of course, the proposal would realize some the long-standing conservative goal of reducing government’s power over health care. It would also reduce premiums for those people, predominantly young or relatively healthy, for whom the 2010 health care law has meant higher premiums or out-of-pocket costs.

No less important, passing Graham-Cassidy would allow Republicans to tell their most fervent supporters that they have repealed “Obamacare” ― and to quiet donors who, according to a recent New York Times story, are “furious” at the GOP’s lack of legislative progress.

That probably goes a long way towards explaining why Graham and Cassidy are still tinkering with their bill, in the hopes of rallying 50 votes; why a vote could still take place, despite the long odds of success; and why the Affordable Care Act’s defenders are still pleading with supporters to make their outrage known.

Here is where key GOP senators stand, based on their most recent public comments. Remember, if Republicans lose any three of the following, the bill cannot pass.

Sen. John McCain, Arizona: He said on Friday he cannot vote for the bill because it is not bipartisan and because it did not go through “regular order,” meaning no committee hearings and no CBO score.

Republican leaders have no way to meet either objection at this point, since Democrats are unified in opposition and, with only days left to pass the bill, it’s way too late to go through regular order. The Senate Finance Committee plans to hold a hearing this week, but at this point in the process such a hearing would be purely for show.

Note that McCain has been strikingly consistent about his insistence on a slow, deliberative, and ideally bipartisan process. He said it was his reason to vote no in July, when he cast a dramatic vote against repeal ― and he said on Friday it was reason enough to stand his ground, even though it meant voting against a proposal from Graham, who happens to be his best friend in the Senate.

Sen. Susan Collins, Maine: Like McCain, Collins voted against repeal in July. Like McCain, she has cited process concerns that Republican leaders cannot address at this point, even if they were willing to do so. Collins has also made a very big deal about the proposal’s impact on coverage ― the cuts to Medicaid, the gutting of protections for pre-existing conditions.

On Sunday, during an appearance on CNN’s “State of the Union,” Collins said “It’s very difficult for me to envision a scenario where I would end up voting for this bill.” It would take a “surprise” from the CBO, providing more optimistic assessments of the bill’s impact ― and CBO has already said it can’t do that in time for a vote.

Collins is the least conservative member of the Senate Republican caucus, representing a state that leans Democratic. She is also a former insurer regulator who knows that many claims Graham and Cassidy make on behalf of the bill are false.

Abortion funding hasn’t come up in the public debate a lot lately, but Graham-Cassidy would defund Planned Parenthood and if that ends up in the final bill that, too, could be a deal-breaker for Collins.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski, Alaska: Last of the trio to vote against repeal in July, she’s also been the most circumspect about her opinion. Like Collins, she has expressed worries about the process and an enthusiasm for bipartisan solutions. Like Collins, Murkowski opposes efforts to defund Planned Parenthood.

Mostly, though, she’s talked about what the bill would mean for her state ― expressing concern about the impact on coverage, but refusing to declare a position until she was comfortable she’d seen all the numbers.

GOP leaders have made no secret of their willingness to modify the bill to win her over, even if that means throwing extra money at Alaska, but so far every estimate shows her state faring worse, provoking criticism of the bill from her governor.

Murkowski’s opposition to the July bill won her plaudits at home. After the vote, she literally got hugs at the Anchorage airport when she arrived. She easily won reelection in 2016, six years after winning as a write-in.

Sen. Rand Paul, Kentucky: Paul has been the bill’s most outspoken critic, though he comes at it from the opposite side of the political spectrum. His beef with Graham-Cassidy is that, for all of its cuts and changes to regulations, it still leaves too much of “Obamacare” in place. On Sunday, as the bill’s fortunes seemed to be sinking fast, he began suggesting that maybe he could get yes after all, with enough concessions.

First he said on NBC’s “Meet the Press” that he’d support Graham-Cassidy if the sponsors just dropped the money the bill earmarks for (partly) replacing the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion ― and then, in an interview with the Washington Post, he said maybe he’d think about a yes if the bill cut its proposed funding in half.

But these are not concessions the bill’s sponsors are in a position to meet. With less funding Graham-Cassidy would leave even more people without insurance coverage, further alienating Collins and Murkowski ― a reality Paul acknowledged in the Post interview.

“Would I talk to them if they said they wanted to make the block grants half as much? I might,” Paul said. “But I’m afraid you get back in the box where the moderates want more and the conservatives want less.”

Sen. Ted Cruz, Texas: Cruz had very little to say publicly until Sunday, when, during an interview at the annual Texas Tribune Festival in Austin, he announced that “Right now they don’t have my vote and I don’t think they have Mike Lee’s either.”

Lee is the Republican senator from Utah and his objection, like the one from Cruz, would sound a lot like Paul ― they all think the Graham-Cassidy bill leaves too much of the Affordable Care Act’s spending and regulations in place.

It’s anybody’s guess whether Cruz and Lee would really vote no if they held the decisive votes ― if they were really all that stood between Republicans and a successful effort to repeal the 2010 health care law. Some are skeptical of Paul’s opposition for the same reason.

But their skepticism is one more reminder that Republican leaders find themselves torn between two competing imperatives ― to reduce federal spending and regulation on health care, while somehow helping people to get better, more affordable coverage. They’re going to keep running into this very same problem, no matter how many times they keep trying.