In 2015, some 303,000 women died from childbirth or pregnancy-related complications. Yet that figure, disturbing as it is, is dwarfed by the number of young mothers who suffer injury, infection and disease after giving birth. According to the World Health Organization, these casualties measure in the dozens for every one mother who dies; and for the million infants who are left motherless every year, many do not survive past the age of two.

These figures may seem shocking in the U.S. where, despite a recent increase in maternal mortality (largely driven by obesity, doctors say), there were 17.8 deaths per 100,000 live births. Compare that to the Central African Republic, where the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is 880 per 100,000 deaths; or Chad, 980; or Nigeria, where the MMR can reach 3,200 deaths.

Worldwide, most maternal deaths (62 percent) occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and 14 percent occur in Nigeria alone. It was in 2008 that Dr. Laura Stachel witnessed this tragedy firsthand.

Hospitals Are Operating in the Dark

A board-certified obstetrician with fourteen years of clinical experience, Stachel visited Nigeria in 2008 as part of a research initiative to lower the country's MMR. Working with the clinicians for 10-14 hour days, it didn't take her long to identify the primary obstacle.

"These same places with high rates of maternal mortality are also places that have energy poverty," she told Planet Experts at the Earth to Paris summit this past December. "They don't have reliable electricity and those that are attached to the grid often don't have electricity twenty-four hours a day. Due to 'load shedding,' electricity is just allocated for certain hours every day to help facilities along with everyone else in the community."

Load shedding, also known as feeder rotation or rolling blackouts, is necessary in a developing nation like Nigeria. The electrical infrastructure simply cannot support a fully-powered grid. Many areas lack any access to the grid whatsoever. Though familiar with the concept of load shedding, Stachel says she hadn't realized it applied to hospitals as well.

Dr. Stachel experienced a blackout on her very first day of duty. "I remember thinking...I am literally and figuratively powerless here," she said. "I cannot do life-saving maneuvers if I can't even see patients. To be in an operating room when the lights go out, that was the scariest thing in the world to me, realizing that a body is open and there is no light to see what there is to do next. If I hadn't had my flashlight, I don't know how they would have finished the surgery."

The lack of power affects every aspect of hospital function, not limited to obstetrics and gynecology. Without energy, refrigerators can't store blood for transfusions. Operating theaters must close down. Midwives can't read the labels on medication or start intravenous therapy. There's also difficulty retaining qualified staff, because health workers don't want to work in unsafe conditions. Some healthcare facilities have burned down after accidents involving kerosene lamps or candles.

"If you can't provide a safe, reliable form of electricity, then health workers don't want to stay in these facilities," said Stachel. "I've been to health facilities that have burned down because the kerosene lantern or the candle that was being used for light caught fire in the health facility, and I've met with midwives who are too frightened to go to work at night because they're scared to go into a pitch-dark place."

The intermittent nature of the light means that the threat of rape or molestation is ever-present for female clinicians.

Building a Solar Suitcase

Backup generators that run on gas or diesel fuel seem to be the natural answer to intermittent electricity, but fossil fuel generators, said Stachel, are fraught with problems. First, many hospitals don't have them, many more can't afford them. In addition to being bad for the environment, they're also noisy, often break down and constantly require fuel. Some healthcare centers are so remote that it's difficult to bring in any supplies, let alone a regular quota of gas. And that gas is costly, which limits the number of hours that generators can be used.

But there is another form of energy, one that is clean, renewable and inexpensive: Solar power. It's a form of energy that Dr. Stachel is very familiar with. Her husband, Dr. Hal Aronson, is the co-creator of Solar Schoolhouse, a solar education program for California students, and has taught about renewable energy in Northern California for over 13 years.

From Nigeria, Stachel wrote to her husband asking if he could design a simple solar system for the hospital she was working at. She wanted to provide power to the labor room, operating room and laboratory. It would have to be small, something she could pack in a bag to bring back as a demonstration. Aronson would go on to create the prototype for the "Solar Suitcase," the tool that would become the cornerstone of the We Care Solar (WCS) mission.

The system Stachel brought to Nigeria was only meant to be a demonstration kit, but enthusiastic workers told her they could use it immediately. Stachel agreed to let the hospital use it while she raised funds for a larger system, but that decision precipitated a movement that has been gaining strength ever since.

"The moment we put that system in, other clinicians from outside the area said, 'Why are you only helping the big hospital? We are also in the dark.' And at first I said, 'Look, I'm not an organization. This is just one project my husband and I are doing,' but then we thought, maybe if we could package things in a small suitcase that would be a way to get them to more health centers."

From that point, Stachel would pack solar equipment with her every time she returned to Nigeria, distributing the pieces to one clinic after another. Her work caught the attention of the New York Times and before long she was flooded with requests from clinics around the world. "That's when we realized this was an international issue," said Stachel, "and that's when we started to really apply for major funding."

The organization received initial grants from the Blum Center for Developing Economies at UC Berkeley and the MacArthur Foundation. More recently, the United Nations has taken notice, and in September it honored WCS with the Department of Economic and Social Affairs' "Powering the Future We Want" award.

Environmental Justice and Social Justice Are Linked

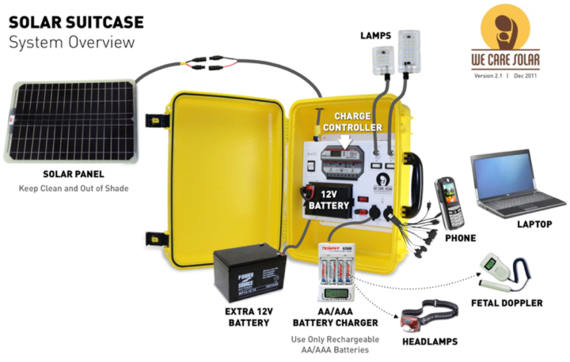

Today, the basic We Care Solar Suitcase is a complete system that includes two 20-watt solar panels, a 14 amp-hour lithium ferrous phosphate battery, a 15A charge controller, two headlamps, a phone charger, a AA/AAA battery charger and a fetal doppler (a handheld ultrasound device for detecting the fetal heartbeat). The LEDs provide medical quality lighting, there are no moving parts and the fuel (sunlight) is free and clean.

Because of their small size and utility, Solar Suitcases are also in demand where natural disasters have destroyed electric grids and infrastructure. Units have been shipped to Nepal following the devastating earthquake in 2015 and to the Philippines following Typhoon Haiyan.

"We're trying now to light up entire regions," said Stachel. "We would like to do country-wide initiatives, so women no longer have to bring a candle with them when they're going into a health center."

According to Stachel, there are an estimated 200,000-300,000 health centers around the globe that must operate without reliable electricity. Thus far, WCS has brought light to 1,500 and counting.

Yet despite those large numbers, Stachel's mission remains focused on eliminating the personal tragedies that inspired this solar revolution. WCS is dedicated to the survival of mothers and their children.

"If you're saving a mother's life," said Stachel, "you're actually saving an entire family." In developing countries, she explained, when a mother dies in childbirth, the infant is less likely to survive. Her older children are less likely to go to school and more likely to be malnourished. Her husband is less likely to be as productive. "By saving the life of that mother you're uplifting that family and uplifting the community," said Stachel.

It is a benefit to both the planet and its people, she said. "I guess one of the big messages here is, environmental justice and social justice are really linked. Something that's good for the environment is actually also really good for trying to empower health workers and saving the lives of mothers and children."

To learn more about We Care Solar, visit their website and Facebook page.