"...let us sit upon the ground/And tell sad stories of the death of kings," stoically laments Richard of Bordeaux to his surviving band of loyal retainers on his return to his once divinely held kingdom of England.

That "let us sit" in Richard II is a last gasp of imperious dictum from a monarch in decline. And it retains its impact today.

Indeed, BAM's Harvey Theater is having a remarkable Shakespeare run, presenting the Royal Shakespeare Company's Henry IV, Part I, Henry IV, Part II, Henry V and Richard II. An ambitious undertaking for both the actors and audience, periodically staged as a kind of Elizabethan Ring Cycle, it is an impressive production. Despite a few missteps, overall it is entertaining and enlightening, boasting some truly amazing performances.

All four plays are directed by Gregory Doran.

What ignites the power of this Henriad -- the quartet of history that Shakespeare turned out chronologically between 1595 and 1599 -- is the friction created when an old world governed by the divine right of kings rubs against a new cultural paradigm of political exigency.

It results in justification for the ambitious Henry Bolingbroke to seize the crown of his ineffectual, divinely installed cousin Richard II and install himself as Henry IV. Though discrete dramas and comedies in a range of styles, the four plays are relatively contiguous in time and together, comprise a cavalcade of the three English monarchs who reigned in the 45 years between 1377 and 1422.

Played with a kind of exhausted grandeur by David Tennant (of Dr. Who fame), this Richard's primary motivation seems to be his ongoing fascination with his own suffering at the hands of political operatives.

Tennant's best work is in the abdication scene, where Richard has a clearly objective understanding of the inexorable events in which he is trapped. He becomes mesmerized with watching his own ruination in a kind of narcissistic passion play, in which he is both the Christ figure and the audience of one.

He is the lone witness to his own crucifixion, for in his solipsistic mind, who else but he would be fit to observe the irony of this pathetic spectacle?

Shakespeare's only play written entirely in verse, Richard II is an oddly inert political drama surrounding a modern character study that verges on the existential. The chronicle of events leading up to Richard's dethroning is relatively straightforward, but as in all of Shakespeare's history plays, it is the world behind the affairs of state where the human drama resides.

Though there are glimpses of internal power struggles at court in the three Henry plays, the humanity there is found primarily in the comic scenes populated by the motley drunks, pimps and whores of Eastcheap.

Unfortunately, in writing Richard II, Shakespeare had not yet struck this vein of comic gold. There is a kind of unrelenting aristocracy in Richard's world, which gives the play a uniform tonality that emphasizes Richard's slow march to doom. As a result, director Doran tries too hard at times to force laughs where none exist.

Sacrificed on the altar of comic relief are the Duchess (Sarah Parks) and Duke of York (Oliver Ford Davies) and their son, Aumerle (Sam Marks) who, in this production is also suggested to be Richard's kissing cousin. (We even have a salacious moment of their canoodling on the castle ramparts.)

Aumerle's insurgent "stand by your man" allegiance to Richard nearly separates his head from his shoulders when his father's opposing loyalties turn state informant. When Lady York rushes to plead for her son's life, the resulting family eruption is presented as if your wealthy neighbors were having a drunken brawl out on their lawn, robbing the familial suffering of its dramatic pathos.

Still, the quartet is an ambitious effort. And though the cast can be uneven, there are also genuine rewards, moments of theatrical magic.

The luminous Jane Lapotaire makes a heartbreaking Duchess of Gloucester, while Julian Glover epitomizes the congenital statesmanship of John of Gaunt and Matthew Needham is terrific both here as the young Harry Percy and later as the mature Hotspur of the Henry plays. Needham's performance is the most consistent of the four-play saga.

Once Richard is dispatched and we enter into the realm of Henry IV, we can sit back in our seats and prepare to laugh. It quickly becomes clear that the bookended reign of this titular king is but a delivery system for one of Shakespeare's greatest creations: Sir John Falstaff (Anthony Sher).

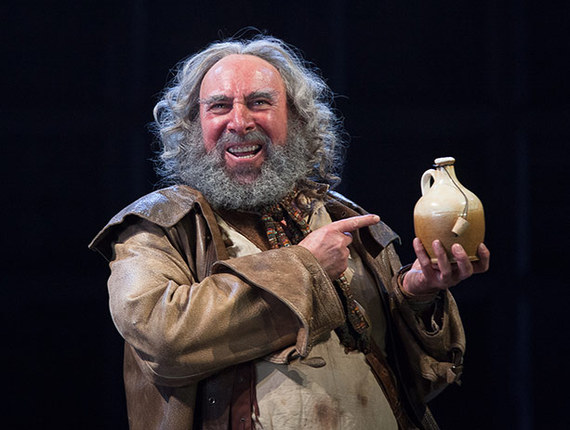

From the moment he is unveiled, emerging strenuously from beneath a filthy sheet, we are in love. It is only the first of many revelations in Sher's masterful performance (right). The audience soon develops a kind of polite tolerance for the exploits of the pompous and guilt ridden Henry IV, but all they can really think about is Falstaff's next entrance.

Though not the usual physical stature for actors cast in the role, Sher makes up in comic inventiveness and sheer magnetism what he lacks in altitude. His portly generosity uplifts every other actor lucky enough to share a scene with him. An expansive performance like Sher's never steals focus from his fellow players, but illuminates them.

He is well supported by his motley band of tavern carousers, who form a traveling circus with Falstaff in the center ring. Alex Hassel, as the callow and irresponsible Prince Hal, is never better than in his joyously jocular exploits among his surrogate father Sir John and the inebriated denizens of Cheapside.

The scene in which he and Falstaff in turn impersonate Hal's gravely pompous father the king has the chilling bite of a death foretold. When we later see Hal at court or on the battlefield, it is almost as if he has faded in color by drifting from Sher's sunny influence to the dark side of the moon.

Unfortunately, Hassel's Prince Hal never quite regains his center of gravity until the final scenes of Henry V. For most of Henry IV, Part II and Henry V, he seems to be wandering aimlessly around the battlefield, looking for where he might have dropped his character.

Even the great, rousing battle speeches become somewhat muted. Hassel is not well-supported by his director, who chooses to try and wrench intimate moments from speeches of public discourse. Even Henry's galvanizing St. Crispin's moment plays a bit like a spelling bee coach psyching up his troops for the regional finals.

It is not until he encounters the radiant Jennifer Kirby, as Princess Katherine of France, that Hassel's Henry V seems to remember that he is King of England. Their wooing scene together is beautifully realized in its awkward tenderness, as their two young hearts become annealed to historical inevitability.

This versatile actress is also well matched in Henry IV, Part II as Lady Hotspur, opposite the equally talented Needham. In Henry V, Ms. Kirby's adroit handling of the "English lesson" scene, where we first meet Katherine in the company of her tutor and lady in waiting, is spectacularly successful.

It economically establishes, in just a few minutes, this princess's history of spoiled indulgence, as well as her willful intelligence and dreams of love. This modest scene, spoken almost entirely in French and fractured English, coupled with the innovative dramatic use of the character of Chorus throughout Henry V, is noteworthy.

The Royal Shakespeare Company's impassioned handling of the tetralogy succeeds in supplying majesty and humor, as well as deftly revealing enduring truths.