I want to thank those who create the amazing devices that make my diabetes easier to manage and help me stay healthier. That said, there's a cost to new technology and devices we never talk about. It's the one to patients. And I'm not talking financial.

While devices lighten the burden of managing my disease, they also create new burdens.

Patients who use devices must among other things:

- Invest time, effort and brainpower researching which device, among the many, are best for them

- Often spend time and aggravation dealing with their insurance company

- Spend time in training sessions learning how to use their device

- Know what to do when devices err

- Manage potential danger to one's health when devices fail

- Be cool-headed and adaptable when the data makes no sense

- Upload data for their own and provider's use

- Make space on their body and give up their vanity

- Find accessories for, and carry around, a ton of equipment and backup supplies

- Sit on the phone with customer service reps at all hours of the day and night

As tiring as it is to manage a chronic illness like diabetes, managing devices adds another layer of complexity and fatigue. And, as invisible as my Type 1 diabetes is to everyone, the responsibility of managing devices is also invisible.

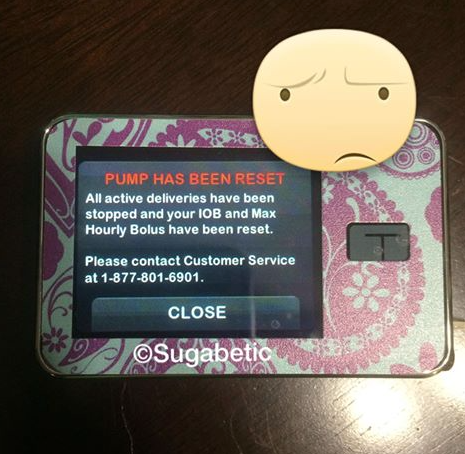

I see a steady stream of this on my Facebook page -- "Soooo, this happened again. Called Tandem... sending me out a new pump (again) since this is the second time it happened...

I hope that by acknowledging the burden patients bear using devices, device developers, health care providers and insurance companies will do more to lighten it.

Device engineers and designers need to spend more time understanding what a day of living with and managing diabetes is like. Many rarely even speak to patients. Digging deeper into the patient experience would lead to devices and technologies that better serve our needs and fit more seamlessly into our lives. Aka more convenience, less hassle.

Health professionals should understand that when they equip a patient with an insulin pump or a continuous glucose monitor, even sometimes an insulin pen, it's not necessarily "problem solved." It's often the beginning of new challenges.

For example, fitting the time that devices require into one's life. Taking pains to prevent or address rashes that occur from devices' adhesive. Stressing out because you forgot to put your CGM receiver into a changed purse. Dealing with insulin pump tubing that gets caught on doorknobs or blocks the flow of insulin, sending one hurtling toward dangerous Diabetic Ketoacidosis.

Empathy and support from health care providers would go a long way.

Insurance companies must accept that there may be extra financial cost involved to using devices and allow for it because technology sometimes fails.

My Trial

Finally, there is another cost to devices -- a psychological one. Can we trust the information our devices give us? Do we feel safe using them?

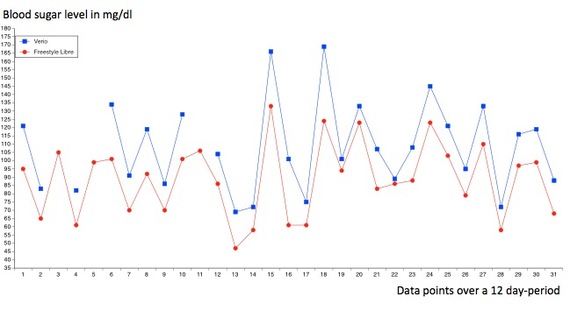

I just conducted my own device trial. For a week I wore my Dexcom continuous glucose monitor (CGM) and the new Freestyle Libre flash glucose monitor from Abbott (currently only available in Europe and the UK). I wanted to compare their performance and the data they gave me.

Dexcom receiver on left, Freestyle Libre reader in middle (3.9 mmol/l = 70 mg/dl). My meter on right. Photo courtesy of Riva Greenberg.

Dexcom receiver on left, Freestyle Libre reader in middle (3.9 mmol/l = 70 mg/dl). My meter on right. Photo courtesy of Riva Greenberg.

As you can see on the graph below, and as is depicted in the photo above, the Freestyle Libre (red line) ran almost consistently 20 to 30 points lower than my meter (blue line). Since my Dexcom is calibrated with my meter during the trial it tracked pretty closely with it.

The Freestyle Libre, however, has no mechanism for calibration. So while that means you get a glorious 14 days (life of a sensor) with no finger pricks, how do you know which device and data to trust? These numbers are what I base my everyday life-saving/life-threatening decisions on.

Trial Two

To see if I'd get the same low bias from a second Freestyle Libre sensor, I ran the trial again. Or hoped to. The day I put on the sensor, it fell off within three hours. It happened somewhere between my home and the grocery store. Likely it got knocked off by the backpack I use to carry groceries.

The Freestyle Libre sensor is only approved for use on the back of your upper arm. It would seem the designers should have considered the limitation of this single location.

The Dexcom sensor I had put on for Trial Two malfunctioned on the fourth day. Dexcom is approved for seven days of wear. I called Dexcom. A pleasant customer service rep said they'd send a new sensor.

But it cost me 20 minutes on the phone and the first day investment I always make in a new sensor. It's not until day two, after 24-36 hours of warm up and calibration, that my Dexcom tracks with my meter.

Diabetes devices are life-enhancing. For the most part they give us remarkable capacity to better manage our health. I well remember 40 years ago when we didn't even have glucose meters.

But we must recognize that new technology also adds effort, frustration, discomfort, confusion and expense to patients' lives. Let's design devices with the aim to lessen those costs.

In actuality, we're still in the Beta phase when it comes to medical devices. And it's patients who bear the work and weight of testing them each day.

Disclaimer: I was not asked by Dexcom, Abbott or any other device company to write this article.

Note: Glu, the online Type 1 diabetes research community, is studying the impact of diabetes technology on partners of people with diabetes who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors. If you'd like to participate, please click here.

Riva's latest book, Diabetes Dos & How-Tos, is available in print and Kindle, along with her other books, 50 Diabetes Myths That Can Ruin Your Life and the 50 Diabetes Truths That Can Save It and The ABCs Of Loving Yourself With Diabetes. Riva speaks to patients and health care providers about flourishing with diabetes. Visit her websites DiabetesStories.com and DiabetesbyDesign.com.