Regulation in Travel Distribution

A spate of lawsuits is emerging between the travel industry's "Global Distribution Systems" ("GDS") and their customers. The first two lawsuits were filed by US Airways and American Airlines; other lawsuits, possibly including a federal antitrust suit brought by the Department of Justice, may follow. Indeed, on May 20, 2011, American Airlines issued a statement announcing that it is cooperating in an investigation with the United States Department of Justice ("DoJ") regarding whether the GDSs have violated antitrust law, and American is currently suing Travelport, Orbitz, and Sabre for alleged antitrust violations.

These actions are interesting for several reasons. First, the conflict upon which these disputes is based has profound implications for the cost and convenience of travel within the United States, especially travel by individual leisure passengers. Second, it had been an article of faith among the netarati that the kind of abuses alleged in these disputes simply could not arise, because the transparency and open access of the net had rendered this kind of dispute, and the alleged abuse of power that the disputes represent, obsolete. Third, because of the widely held belief that this type of abuse is no longer possible, there is a significant danger that the wrong decision may be reached in one or more of these cases.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, the analysis we present here has widespread implications in Internet regulation. It suggests that antitrust may not be the most appropriate way to approach disputes in online digital distribution businesses. An alternative measure, third party payer system power, may be more applicable in adjudicating these disputes, than "share of relevant market" or "essential facilities" arguments offered in antitrust litigation. We have argued elsewhere that the unique structure of online distribution systems may give them the power traditionally associated with monopoly, even in the presence of what appears to be a competitive marketplace.

The issue of third party payer power in online distribution may be especially helpful in rethinking the regulation of online businesses since antitrust litigation has fallen out of power in the US. Likewise, the essential facilities doctrine increasingly is viewed as inappropriate or irrelevant to antitrust regulation. And yet there does appear to be a growing body of disputes and competitive harm that require some integrating theory for their resolution, and third party payer mechanisms may provide this integrating theory. The FTC has recently launched an investigation into Google's business practices; whether you are an avid fan of Google and believe this is an assault on capitalism, or believe that the investigation is long overdue, the resolution of these third party payer disputes in air travel will have bearing on any future litigation involving Google.

The present story addresses the history of distribution, power, and abuse of power in airline reservations, and an explanation for why the abuses that required regulation in 1984 were believed to be impossible in an internet age. Indeed, the likelihood of abuse seemed so remote that the industry was deregulated in 2004. A subsequent piece, to be published later this week, explains why the distribution of airline reservations has not evolved as expected, and why reregulation may be required.

Analysis of the Changing Role of Power in Travel Distribution

The essence of the disputes is very simple. US Air and American have products and services that they want to offer travel agents that the GDSs are currently not technically equipped to offer; the GDSs' "full content" requirement prohibits airlines from offering any product to a travel agency unless that product is already available through the GDSs. This limits the options available to US travelers who book through agencies. Additionally, many airlines would like to offer their services through some form of direct connection to agencies, which would greatly reduce their airlines' distribution costs without affecting the quality of service provided to customers by their agencies; a range of contractual restrictions and contractual incentives limits airlines' ability to offer direct connection and agencies' willingness to accept them.

The US Airways complaint against Sabre, Inc. ("Sabre") alleges, among other things, that Sabre has engaged in behavior to restrict US Airways' ability to use lower-cost and more efficient means of connecting with travel agencies, including entering into exclusivity agreements with travel agents, charging artificially high prices to US Airways, and restricting US Airways ability to offer products without first offering them on Sabre. The American Airlines complaint alleges, among other things, similar allegations of exclusivity contracts and artificially high prices and alleges that Travelport and others retaliated against American Airlines for offering direct connect technology to travel agents by doubling American Airlines' booking fees for international reservations to make them appear more expensive. In the former case, US Airways had entered into a contract with Sabre, and subsequently filed its action against Sabre. American Airlines, on the other hand, filed its actions following unsuccessful negotiations with Orbitz regarding its bookings, which allegedly resulted in Travelport and Sabre retaliating against American Airlines. American Airlines continues to work with Travelport and Sabre during the dispute; indeed, for reasons described below, it really must remain present in both systems whether or not it is able to negotiate terms it considers commercially reasonable.

Indeed, excessive fees are one of the hallmarks of third-party payer systems. As we have described elsewhere, over the course of more than two decades of research, the prices charged by third party payer distribution systems are generally able to escape the discipline of the market, even in the absence of traditional monopoly power. Travel agents are paid to use GDSs, and they are happy to use them. Airlines pay to be included in distribution systems, not only to be found, but to not be not found. As long as agencies still account for a significant portion of travel bookings, and they do, and as long as agencies use GDSs, then most mainstream airlines really do not have a choice and really must pay the fees these GDSs charge. For example, American Airlines has alleged that it pays tens of millions in booking fees to GDSs, which are shared with the travel agents that use the GDS' systems. This is alleged to result in travel agents frequently selecting the GDSs that charge the highest booking fees to airlines and thus are able to provide the highest payments to the agencies; this is, of course, the very opposite of price competition. In summary, the travel agents receive the service more free than free, subsidized out of the millions of dollars that airlines pay in booking fees. Why doesn't the traveler object? Quite simply, travelers do not directly pay the fees that the airlines are charged, and indeed do not even see them; most travelers are not aware either of these disputes, or of the fees that are the basis of them. Why doesn't American or US Airways boycott the GDSs? Traditional full service airlines like American and US Airways still rely heavily on corporate travelers, they therefore still rely heavily on agencies, and they cannot survive the loss of business that they would suffer from vanishing from one or more GDSs.

But how can the GDSs still have the power and the relevance to force their will on an airline? How can they even be worthy of a legal complaint? How can any of this still be possible? Isn't this a vestige of pre-internet technology and pre-internet business models, without relevance today? Don't airlines have websites that customers can use to directly buy tickets? Don't Orbitz and Travelocity represent alternatives? Don't agencies represent alternatives?

Well ... not exactly. Orbitz, Travelocity, and traditional travel agencies use the GDSs, and indeed most use only one GDS. For example, Orbitz has entered into an exclusivity contract with Travelport, whereby Orbitz is required to use Travelport "exclusively" as its GDS provider for North American air travel bookings through 2014. An airline that vanishes from one GDS vanishes from all of the agencies that use that GDS. These GDSs represent what we have previously called parallel monopolies, and even in the absence of traditional monopoly market share, a GDS can cause any single airline to vanish from a share of the agencies, causing enormous harm.

For most airlines, direct distribution has not succeeded because customers still use agencies (on or off line) and agencies still use GDSs. Let's see why. But first, a brief historical background on previous disputes in this industry provides useful insight into how the current disputes may unfold.

Background on Reservations Systems and Distribution Systems

In the 1980s, long before the internet, customers used travel agencies to book tickets, and travel agencies used Computerized Reservations Systems (CRS) to search for flights, based on times and fares. Customers had no alternative to their agencies, and agencies had no alternative to a CRS. Moreover, the CRSs paid the agencies to keep them happy, the vast majority of flights were booked through CRSs, and CRSs had almost unlimited power to charge airlines for listing in the CRS database. Indeed, in the early 1980s American Airlines made more money selling Delta's flights through Sabre than Delta did operating them, and United earned more selling other airlines' flights through Apollo than it earned operating an airline.

This is an early example of what we now call a third party payer business model: Travel agents (party 1) used the CRSs (party 2) to find airlines (party 3). The agencies were happy (they received free service and were actually paid for their use of CRSs) and they seldom switched CRS vendors. Airlines needed to be found, and so they (party 3) paid CRSs almost whatever they demanded, not so much "to be found" as "to not be not found." It was not necessary that any CRS have monopoly power to make this business model work, as long as each CRS operated as near monopoly for the agencies it served; if a CRS droped an airline, then the agencies that use only that CRS will no longer see the airline's flights and bookings through that CRS will almost vanish. The impact of this can be catastrophic for the airline. For example, in the 1980s, when Sabre dropped Braniff's flights, and when Apollo dropped Frontier's flights, each airline lost enough business to be forced into bankruptcy, even though each airline could still be booked by agencies served by the other CRSs.

Ultimately, the court decided that the power of Sabre and Apollo was excessive and that it had been abused, and the travel distribution industry became heavily regulated. This is explained in several of our previous papers (see, for example, our paper prepared for the Searle Center Conference on the Economics and Law of Internet Search).

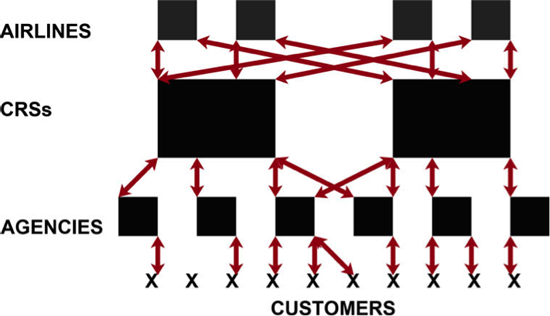

The structure of the industry, as it existed in 1984 (that is, before CRS regulation), is shown below in figure 1.

Figure 1--The structure of travel distribution, as it appeared in 1984, with most customers using agencies and most agencies relying on a single CRS.

Of course, in an Internet age, this business model now appears totally anachronistic, toothless, and without power. Customers do not need to use agencies; they can go directly to the airlines own booking systems. In theory, customers will go directly to airlines to arrange bookings. Similarly, in theory, agencies do not need to use Global Distribution Systems (The GDSs that replaced CRSs); they, too, can go directly to the airlines' own booking systems.

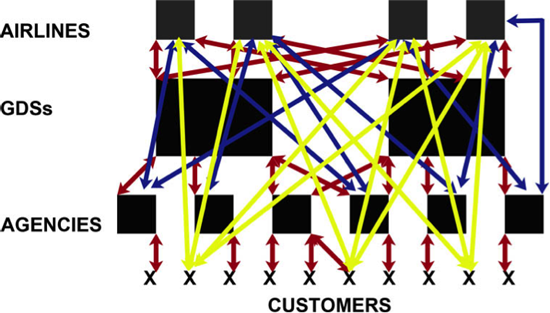

The new structure of travel distribution was expected to look as shown in figure 2. Agencies can bypass GDSs, and customers can bypass agencies and GDSs; how could any residual power exist? So we all -- consumer advocates, regulators, airline executives, and industry researchers alike -- stopped worrying.

Figure 2.--The structure of travel distribution, as it was expected to look today, with airlines appealing both to agencies and directly to customers, bypassing GDSs. The new yellow lines, not present in figure 1, represent customers bypassing GDSs and agencies by booking directly from airlines' own websites. The new blue lines, also absent from figure 1, represent agencies bypassing GDSs and booking directly from airlines Many of the red lines, representing usage of traditional distribution systems, have been eliminated.