Update below.

This situation in Egypt remains fluid and is not fully understood in America, and yet American politicians obviously need both to set U.S. policy and to take concrete actions, and they need to do both quickly. Probably the most important question to address is what the US can do to help the Egyptian people, or, at least, to do no harm to the Egyptian people. It's not always clear that American actions are focused on American ideals or on American interests, if the relationship between long term and short term interests is balanced, or even if the risks of action and inaction are fully understood.

We really do not know how big the protest movement is yet. We know that only a small fraction of Egyptians may be directly involved, but we do not know whether a small fraction or a large fraction of the Egyptian population is indirectly supportive. But based on our own history we have reason to believe that they have already demonstrated their significance.

In our own recent past, the demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968 did not represent all of America, but they were not unimportant. They did succeed in producing "regime change," driving off Lyndon Johnson and his heir apparent, Hubert Humphrey. They brought about the Nixon Presidency, which was not exactly what the protesters had in mind, and the effects on Americans, and on Vietnam half way around the globe, were profound.

We do not know how popular the protests are in Cairo or what will come next.

It is now common for Americans, from members of the media to politicians, to bash intelligence services for not foreseeing the Egyptian crisis. Everyone who studies the politics of the Middle East knew that something was going to happen. Indeed, this was clear to all intelligence services, not just those focused on the region. The Chinese have been watching social nets, anti-regime activists, and the role of the military around the world, at least since the green revolution in Iran after contesting elections in 2009. The Iranians have been watching these three factors play out through out the Middle East, certainly at least since 2009, as have the Israelis.

So, if we all knew, why do we look so surprised? Everyone knew something in Egypt was going to blow, eventually, and create a flashpoint. We knew that social media, or some form of self-organizing communications, would be used to organize protests, and to try to turn the army away from loyal and unquestioned support for the regime. And we knew that whether or not the army continued to support Mubarak's party would play a critical role in determining the outcome.

We've always known about flashpoints. The Germans cooperated in sending Lenin back from Switzerland, in part to cause a flashpoint that would fully disable Russian participation in the First World War. Centuries earlier, the Spartans offered freedom to any helot willing to serve in their army, and then killed all who volunteered; the last thing the Spartans wanted was brave, organized slaves creating a flashpoint of resistance to Spartan rule.

Likewise, we have known about social nets and political organizers for years. In 2009 the Green Movement and the protest over elections were organized through Twitter and Facebook. In 1979 resistance to the Shah was coordinated with Khomeini's tapes smuggled in from France. There is some debate about whether messages baked into chapathis were used to coordinate the Indian Uprising of 1857. And for low tech mechanism for organizing resistance, it's hard to top Madame Defarge's slowly knitting her record of the abuses of the Ancien Regime in A Tale of Two Cities. Organizing resistance is about coordination, not about Twitter and Facebook, although modern technology does make flashes faster.

Likewise, we have known about the role of an army. The Czar abdicated when his troops would no longer fire on their fellow citizens, as did the Shah, as did Gorbachev.

Although we knew that a flashpoint would arise, and we knew the importance of the army to the evolution of the situation on the ground after a flash, we still don't know what the Egyptian army will do. The highest levels of the army are probably loyal to a regime that has produced personal wealth and power, and personal prestige and honor, for them. Senior officers of course are also concerned with, and loyal to, the State of Egypt. In one sense, the military may be almost inseparable from the regime; currently, the military may control as much as 40% of the Egyptian economy. The more junior enlisted ranks are torn in many directions, loyal to their officers, loyal to their regiment and its honor and traditions, and loyal to Egypt. What does loyalty to their officers mean, if and when it comes into conflict with loyalty to their brothers, and if the regiment's will starts to shift? Does loyalty to Egypt mean loyalty to their brothers on the streets, or to the Brotherhood? Will the troops support the regime, as in Iran today; will they oppose the regime, as the army did in Russia at the time of the Russian Revolution, or will they merely put down their weapons and enable regime change through their inaction, as the army did when the Shah fell? We truly don't know what they will do next, or what will happen as a result.

So, yes, we knew that something was going to cause a flash, and we knew the factors that would determine the outcome after a flash. But knowing this really is not very helpful, because the actual flashpoints are always surprises. The list of things to monitor did not include the fiery suicide of a young fruit vendor in Tunisia. The trigger for the American Revolution was the Tea Act of 1773, which actually lowered the tax that the British imposed on tea, making it less expensive than the smuggled tea that wealthy Bostonian businessmen had in their warehouses; the simplest way to deal with this new source of competition was to throw the tea of the ships and into Boston Harbor. While the American Revolution was probably inevitable, the flashpoint that resulted from lowering tea taxes probably was not. Flashpoints are always surprises, and even if everyone in authority knew that something was going to happen eventually, the actual cause, and the actual timing always are unanticipated.

The fact that the timing of crises is always a surprise does not mean you cannot prepare, and does not mean that professionals have not prepared analyses. It was always clear what forces would affect the political situation in Egypt after resistance flashed and what the possible outcomes would be.

The first question to address is whether the current situation is stable. Can the current regime, which has been in power for over three decades, supported by emergency powers legislation, continue in power? Can the ruling party select candidates, have them stand for election, and remain in power after the elections, honestly or not? One possibility is that with unlimited use of military force, the NDP and the army could remain in power for some time, either by suspending or by manipulating the fall elections. Another possibility is, indeed, a cosmetic transition, with the NDP being replaced by a collection of oligarchs supported by the military. Both may appear to offer stability, and most may endure for some time. Neither is consistent with the desires of the Egyptian people or with American ideals, and both are probably quite dangerous. Ultimately, this illegitimate government will fall, and it is likely to be brought down with a hard crash. From outside, the prospect of a new non-democratic state, engineered by the military or by Mubarak's supporters, seems dangerous enough to be marked in bright red. For the good of a secular Egypt and for the Egyptian people, the NDP should start preparing now for their inevitable exit after the next elections.

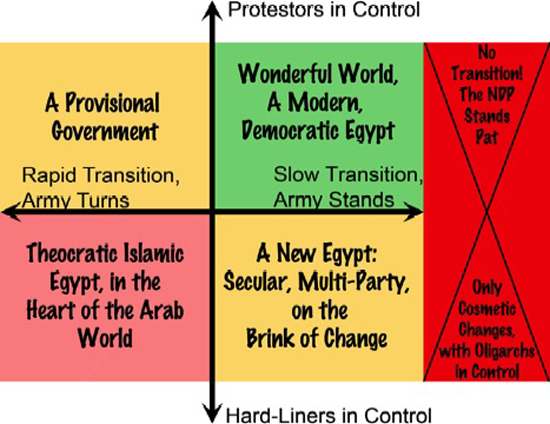

Assuming that the NDP does exit and that we have a real transition in governance, we see four possible scenarios, as shown below. We knew what the options were years ago, and they remain clear now. Unfortunately, we still don't know which is going to emerge, and the answer is of vital importance to Egypt, to the Middle East, and to the United States. As we discussed above, a scenario in which there is no meaningful change, or no transition, is probably not a sustainable option, either for the NDP or for the military, and while we do not discount it we do not discuss it further. As all practitioners of scenario analysis know, the actual alternatives are not as stark and distinct as they appear here; there may be a speed at which rapid transition to a democratic Egypt is possible, or it may be possible that even under a planned transition democracy does not emerge. The four scenarios here do appear to be determined by visible forces, and they do appear to be consistent, logical outcomes determined by those forces.

Wonderful World: The scenario the United States would prefer, and that might well best serve the interests of the Egyptian people, is a slow transition, allowing sufficient time for the widest range of parties, forces, and interests in Egypt to organize and coordinate, and for a true stable multi-party democracy to emerge, with this democracy coalescing around the idealistic young demonstrators we all see nightly on television. This is shown in a reassuring (traffic signal) green. While the US has no intrinsic right to achieve the scenario that it most desires, if this scenario is also the best for the Egyptian people and consistent with the democratic principles of the US, any actions we take should be carefully calculated not to interfere with the emergence of this scenario.

A New Egypt, Secular, Multi-Party, but on the Brink of Change: In this scenario the diverse collection of demonstrators are unable to form a stable government. The only coordinated resistance movement in Egypt with an internal structure, established systems of communications, and a disciplined leadership in contact with funding sources outside Egypt, is the Muslim Brotherhood, and in this scenario they form an Islamic Republic. The army remains an effective secular counter-weight, as it has in Turkey since its inception as a modern republic. This could transition either to a full participatory democracy (the green scenario above) or to an Islamic theocracy (shown to the left in a dangerous red). For that reason we show this scenario in cautionary yellow. It is easy to discount this scenario, because the youthful protestors do not take the Brotherhood seriously either as a "cool" movement part of the protest, and because both the Brotherhood and Iran/Hamas/Hezbollah are not a visible presence. However, it may be wishful thinking to assume this means that they are not still a serious force.

A Provisional Government: If the Army stands aside quickly, the largely disorganized demonstrators may obtain control and install a provisional government. The demonstrators can be forgiven for not having much prior government experience or much of a political following; after three decades of rule under emergency powers legislation, no one outside the government has either. Even though the transition appears uncomfortably rapid, if all goes as well as can be hoped the protestors may still have time to form a democratic government. A shift to the green Wonderful World scenario on the right is possible.

But it is not clear that there is anyone among the youthful demonstrators who can actually form a government. The same unstructured, headless, self-organizing structure that makes the resistance so hard for the government to control, simply because it has no leaders who can be turned or neutralized, may make it difficult to form a government that can take power and assert control.

If the provisional government is not able to assert control, or is not able to protect the Army's substantial economic interests, the Army may not support the Provisional Government, as when the Russian Army, after allowing the Czar to fall, refused to support Kerensky's Provisional Government. The Government called on the best organized and best armed force it could to help it support itself, Lenin, the Bolsheviks, and the Red Guards, which from the start made it clear they were fighting against the Government's opponents, but not for the Government. After months of chaos and civil war, Russia's Communists emerged firmly in control, where they remained until the fall of the Berlin Wall. Ultimately, the Islamic Brotherhood, with support from Hamas and Hezbollah, and from Iran behind them, may overthrow this provisional government, either swiftly, as the Mullahs coopted the youthful opponents of the Shah, or after violence and chaos, much as the Bolsheviks and the Red Guards were able to overthrow the Provisional Government in Russia. This scenario starts out as promising but could ultimately transition to the dangerous scenario below, and for that reason we show it in cautionary yellow.

Theocratic Islamic Egypt, in the Heart of the Arab World: In this scenario the army turns away from the regime, the regime quickly collapses, and in the absence of any other organized, disciplined resistance, the Muslim Brotherhood seizes control of the government and the media. This can be a rapid power play, over almost before it starts, as the Mullahs' takeover in Iran was, or a slower evolution after chaos and, perhaps, armed struggle, as the Bolshevik victory in Russia was. Our showing this in dangerous red may signify our western biases, but from here it does not appear that the majority of the demonstrators want an Islamic theocracy, and it does not appear that a majority of Egyptians would be well served by that outcome.

If our analysis is correct, it would appear that a rapid collapse of the army, or any other factors that lead to chaos and a rapid transition, will probably empower the only organized and disciplined resistance movement in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood. Although by no means certain, rapid collapse would most probably lead to this red scenario. Perhaps Egypt really does need a more measured and more orderly transition.

And yet it is just as obvious that the bright red scenario on the right would be a disaster for Egypt, for the region, and for America. The NDP and the Army really cannot hold on to power indefinitely, and any attempt to do so would be toppled only by force and might lead to the worst possible outcomes.

Our recommendations to the American administration would therefore be simple:

- Do no harm. Do not so-visibly endorse and embrace the demonstrators that they are seen as American puppets and lose their legitimacy with the Street. We knew not to publicly endorse the demonstrators in Iran in 2009.

- Do no harm. Do not push for change so rapid that the only beneficiary is likely to be the Brotherhood as the only group that is ready to seize power today.

- And do not dither. When we decide what to do, and how to do it, 'twere best done quickly, and openly. The Egyptian military must not see America as having abandoned it. The Egyptian people must not see America as having abandoned them. The regime must know why it has to go.

This is a delicate balancing act. The Cairo Street has to know that this is not America's revolution and America did not try to control it. The street must also know that America did not oppose the will of the Egyptian people, and that America did its best to preserve the ability of the people to chart their own future.

This will not be easy. The Egyptian people need to see Mubarak be very, very unambiguous about when the transition would start (now), where the transition would lead (elections), how the transition would end (with free and fair elections). The Egyptian people need to see how the fairness of the transition would be ensured, and how the safety of the demonstrators would be protected. Perhaps the US, as part of a responsible world community, can contribute to providing these assurances and guaranteeing a safe, orderly, and relatively brisk transition.

Update: After Mubarak's speech, we still don't know what happened. Either Mubarak and the Egyptian military have agreed on a time table for his departure and the transfer of power to a representative government, firmly setting Egypt on the path to our Wonderful World democracy scenario described above, or they have agreed to retain power. Since the Egyptian people do not know what happened, they may respond by waiting or by attempting to force the situation, risking or forcing the military to declare its loyalties through the use or the withholding of force.

The military may respond with force, or it may collapse if and when junior officers and individual refuse to fire upon the demonstrators. Then the regime collapses, and we move towards revolution. Either an unstructured and inexperienced resistance forms a provisional government, or forces of the Islamic Brotherhood emerge and form a government does.

The next uncertainty is what the Brotherhood, Hamas, and Hezbollah do. This Friday or next Friday, if the NDP and army have not established a credible transition path, will be days of great vulnerability. It would be an ideal time to force the issue and see if the army fires or folds. If the army does fold rather than fire on demonstrators, this would create the ideal time for the Brotherhood to emerge and seize control, and their planners know this.

If there is no credible transition AND the Street becomes violent AND the army responds by refusing to fire on civilians AND the Brotherhood emerges as the only force sufficiently organized and disciplined to impose order on the chaos, THEN an Islamic Republic may emerge in Egypt.

That's a lot of ifs. A lot of things can still go very right tonight and over the next week. But a lot of things can also go very wrong. I assume that the leadership of the Brotherhood understands the situation far better than those of us here in the US, and they have pushed this analysis even further. The next several days are will be critical.

Eric Clemons is professor at the Wharton School and a frequent commentator on issues of strategy, technology, risk management, and planning under uncertainty. Julia Clemons is a fourth year student at the University of Chicago, majoring in Political Science and minoring in Near Eastern Languages and Civilization. Liz Gray is a writer, poet, and risk management consultant.